sandbox

The “Sandbox” space makes available a number of resources that utilize and explore the data underlying "Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640" created by the Making and Knowing Project at Columbia University.

Skillbuilding: Preparing and Painting with Azurite

The Making and Knowing Project, Columbia University

Last updated 2022-11-30 by NJR

A downloadable version of this assignment: [PDF]

Presentations & Handouts

- Presentation: Preparing and Painting Blue Pigment in the Renaissance

- See also a short version of this presentation

- Student Handout (to have while doing the hands-on reconstruction)

Introduction

This skillbuilding assignment will introduce you to one of the most common blue pigments in the Renaissance, azurite. You will learn about what azurite is and how it is used in works of art. Following sixteenth-century instructions, you will prepare azurite as a pigment from the mineral ore by purifying it, and then use the pigment to create paint.

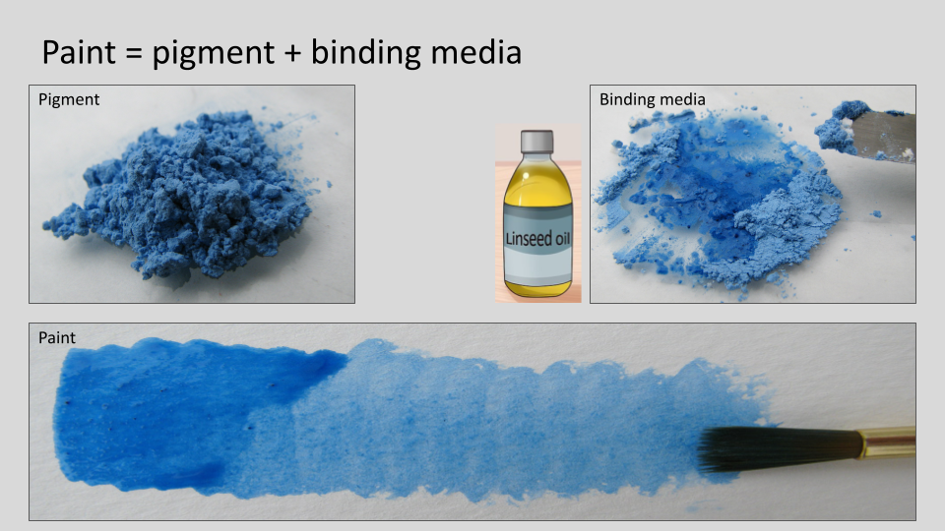

Pigments and Paints

It is important to remember that there is a difference between pigments and paints. A pigment is an insoluble colored particle; in other words, it is usually a dry powder of a certain color that will not dissolve when added to a desired medium or liquid. To create paint, one combines the pigment with a binding medium to create a paste that can be applied to a surface. A binding medium will help the pigment adhere to the surface on which it is applied. Common binding media include linseed and walnut oils (for oil painting), gum arabic (watercolor and ink), egg yolk (tempera), egg white (glair), and animal glues (distemper). For more information:

- Presentation: Introduction to Pigments & Paints

- Assignment: Making Paints from Pigments and Painting Them Out

Azurite

Azurite is a basic copper carbonate pigment [2CuCO3-Cu(OH)2], a common blue colorant found in paintings, drawings, and illuminated manuscripts of the Renaissance. It is found as a natural ore, often co-occuring with the green mineral malachite which is also a copper carbonate pigment. To prepare the pigment, the mineral is ground to a powder, removing any malachite or other impurities. Larger particles of azurite are a deeper blue and as the particles are more finely ground, it becomes paler in color. The different hues can be separated into different “grades”: larger particles (dark blue) are a higher grade of pigment than smaller particles (pale blue). These different grades can be obtained through a process known as levigation, where water is used to separate the smaller, duller particles from the larger ones which sink to the bottom. The smaller (and thus less heavy) particles float closer to the top of the water, which is poured off successively until only the heaviest, deepest blue particles remain.

The Virgin and Child with Saint John (~1480), Filippino Lippi, The National Gallery. Azurite has been found in this painting. See Dunkerton, The Materials of a Group of Late Fifteenth-century Florentine Panel Paintings.

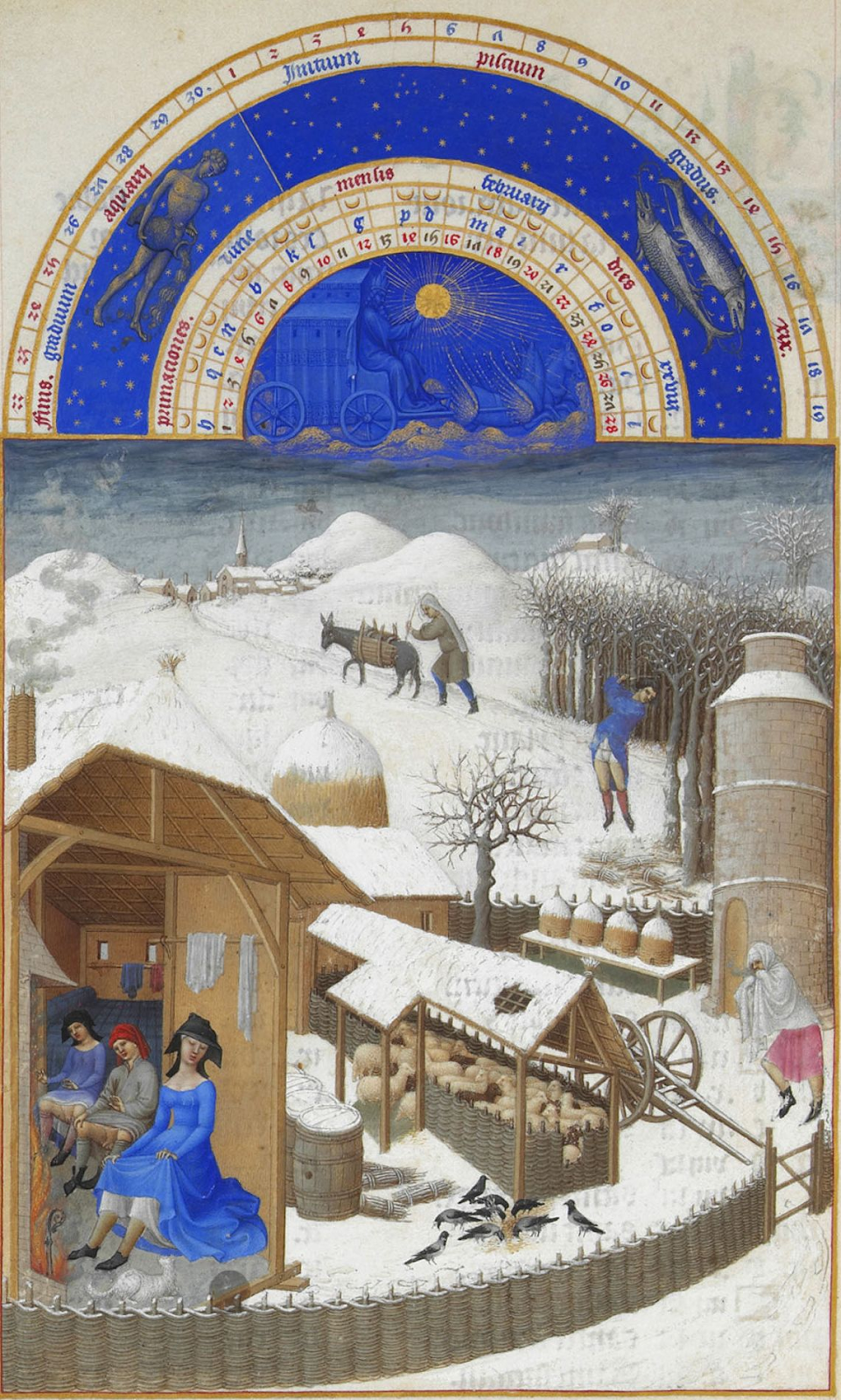

Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry (1412-1416), Folio 2 verso: February.

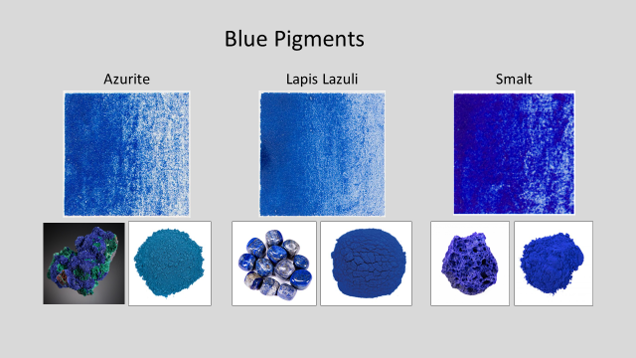

Other Blue Pigments

Azurite is only one of the most common blue pigments in the Renaissance palette. Other pigments include the very costly lapis lazuli (also known as ultramarine), the cobalt blue glass smalt, and the organic indigo. A “synthetic” blue copper carbonate blue, known both as bice and verditer, has the same chemical makeup as azurite but is made by an artisan rather than sourced as a natural ore (for example, by combining copper nitrate and calcium carbonate). For more information:

- The Traveling Scriptorium Pigment Sampler

- Presentation: Preparing and Painting Blue Pigment in the Renaissance

Blue Pigments in BnF Ms. Fr. 640

There are a few notes on various blue pigments in BnF Ms. Fr. 640 (the sixteenth-century artisanal/technical manual studied by the Making and Knowing Project). It is not always clear which blue pigment the author-practitioner is referring to in the processes he describes. Many of the instructions or observations can be interpreted in more than one way. We encourage you to explore the instances of “blue” in the manuscript by:

- Searching the digital critical edition of Fr. 640, Secrets of Craft and Nature, for “azur” - try a wildcard search by entering “*azur*” to catch all variations of the word (enter asterisks on either side of the word as shown here).

-

Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano, eds., Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640 (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020), https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/, https://doi.org/10.7916/78yt-2v41.

-

- Reading the essays:

Folio 11r: “Painting esmail d’azur in oil”

On folio 11r of Ms. Fr. 640, there is an entry that describes a way to prepare a blue pigment called esmail d’azur. It is unclear exactly which blue pigment it refers to, and the processes described could be applied to the preparation of smalt, azurite, something else…?

This is a secret that is hardly known to common painters. Some take the most delicate they can & grind it with ceruse, which binds it, and next prick with an awl in several places the area they want to paint with azur d’esmail, in order that the oil enters & leaks in, & does not cause the azure, which in itself is heavy, to run. Others lay the panel flat & put down the azure on it, which is also done in distemper. The main thing is to grind it well on marble, and before that, to have washed it thoroughly. Some grind it

withthoroughly with an egg yolk & then wash it in five or six waters and lay it on not with a paintbrush, which would be too soft, but with a brush thoroughly softened & crimped, & layering it thickly as if one were putting it down with a trowel; settling down it evens out and flattens. I have experienced that grinding azur d’esmail with egg yolk & next washing it in several waters is good. However, it loses a little of its vividness in the grinding of it. I have also washed it in several waters &, when it had settled a little, I removed the water, stillqblue, with a sponge and squeezed it into another vesselthuswhere it settled, & from the residue I had the ash, flower, and subtlest part of the azure without grinding it, which is the best, for in the grinding of it, it loses some of its tint. Those who make it in Germany compound it like enamel, in large pieces which they pestle, & pass through several sieves & wash.

To make azures beautiful, they wash or soak them in a rock water, as they call it; it is a water distilled from mines where azure or vert d’azur is found, which distills naturally through the veins of the mountain or is distilled through an alembicparfrom mineral stones of azure or copper.

Azure ashes are only good for landscapes because they die in oil. Only true azure holds on. Azur d’esmail cannot be worked if it is too coarse. Try it, therefore, on the fingernail or the oil palette. If it[illegible]happens to be sandy, do not grind it except with the egg yolk or, better yet, wash it in clear water & with a sponge remove the colored water after it starts to go to the bottom, and in this manner you will extract the very delicate flower, which will be easy to work with.

If we consider the way that azurite is prepared by separating out the different grades of the pigment, we can focus on certain passages from fol. 11r to inform our reconstruction of the recipe with azurite:

… The main thing is to grind it well on marble, and before that, to have washed it thoroughly…

… Wash it in clear water & with a sponge remove the colored water after it starts to go to the bottom, and in this manner you will extract the very delicate flower, which will be easy to work with…

Reconstruction: Preparing Azurite

To prepare azurite from the mineral ore, one uses water to remove impurities and to separate the different sizes of particles and obtain different grades of pigment. Any small containers that would allow successive pouring off of water can be used, but one historical tool - that is incredibly effective! - is a mussel shell. During the Renaissance, shells were also used to mix and store small amounts of paint similar to wells in an artist’s paint palette.

Materials

- azurite ore, e.g., Kremer #102005 “azurite stone”

- mortar and pestle (or another way to crush the stone, such as a hammer and plastic bags to contain the pieces)

- glass plates & mullers

- on the side (optional): ceramic plates and plastic palettes

- for pouring/separating: mussel shells or small plastic containers

- large containers of water

- paper towels

- scoopulas or other utensils that may be useful, such as spoons, palette knives, etc.

- to paint the azurite out:

- concentrated gum arabic solution (1g gum arabic in 5ml water), e.g., Kremer #63330

- paintbrushes

- mixed media paper

Process

The process is open to your experimentation! To get started, however, here are some useful illustrations:

- The dedicated slides towards the middle of Presentation: Preparing and Painting Blue Pigment in the Renaissance

- Fieldnotes (with step-by-step pictures) by Naomi Rosenkranz, SU17 Azurite

- “Experiments with Azurite on the History of Design MA Course” by students of the V&A/RCA History of Design MA

- For painting out, refer to Assignment: Making Paints from Pigments and Painting Them Out

Questions for Consideration

- Observation:

- What does the stone look and feel like?

- Other than the blue parts of the stone, what other inclusions (different types of stone) can you see?

- When the stone is ground, what does the powder look like?

- How does it behave in water?

- What do the particles look like?

- Embodied experience:

- What kind of movements do you use in each step of the process (grinding, adding water, pouring, painting out)?

- How does it feel to grind the azurite stone?

- How does it change when you add water?

- Can you manipulate the separation of the particles? How? (time, amount, ratio of water, speed of pouring)

- How many different “grades” can you get?

- When painting the different grades out, is there a difference between the paler and darker colors?

- Is there a difference in the way each paint wants to be handled or flows off the brush?

- Artisanal knowledge:

- What kind of knowledge would you need in order to prepare, apply, handle, appreciate these materials?

- How might you acquire that knowledge today and historically?

- Asking new questions:

- What new questions does this experience cause you to ask about paintings or other works of art in general?

Other Renaissance Recipes on the Preparation of Azurite

It is often extremely helpful to consult other recipe books from similar time periods that discuss the same process or materials. Here are some excerpts for your consideration.

Cennini — Preparation & Application

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook: The Italian “Il Libro Dell’arte”, ed. Daniel V. Thompson (New York: Dover Publications, 2018).

Azzurro della Magna, translated as “azurite” rather than former “German blue”

“the azurite stone, which looks very lovely to the eye, and resembles an enamel.” (37)

”When you have to lay it in, you must work up some of this blue with water, very moderately and lightly, because it is very scornful of the stone. If you want it for working on draperies, or for making greens with it as I have told you above, it ought to be worked up more. This is good on the wall in secco, and on panel. It is compatible with a tempera of egg yolk, and of size, and of whatever you wish.” (35-36)

For painting the blue drapery of the Virgin: Lay down a coat of sinoper and black in a fresco. “Then, in secco, take some azurite, well washed either with lye or with clear water, and worked over a little bit on the grinding slab. Then, if the blue is good and deep in color, put into it a little size, tempered neither too strong nor too weak. Likewise, put an egg yolk into the blue; and if the blue is pale, the yolk should come from one of these country eggs, for they are quite red. Mix it up well. Apply three or four coats to the drapery with a soft bristle brush.” (54-55)

Merrifield — Preparation & Application

Jean Le Begue, “Experimenta de Coloribus (1431),” and The Bolognese Manuscript (15th century), in Medieval and Renaissance Treatises on the Arts of Painting: Original Texts with English Translations, ed. Mary P. Merrifield (New York: Dover, 2003).

“How azure is prepared and purified. —But I shall not conceal how I purify it when it comes to my hands. I first pour it into a bason, and put a little water along with it, and rub it with my finger until it is thoroughly moistened, and then I pour in more water and stir it well, and let it rest. When it has settled, I pour off the water, turbid from the impurities, into another vase, keeping the precious colour which remains at the bottom of the vase, for its nature is such that the finer and purer the colour is the heavier it is, and therefore the sooner it reaches the bottom; and the impurities, or the whitish or yellowish parts, which are lighter, float or remain above it in the water. And, if necessary, I repeat this process several times, pouring water out and in until it is purified” (Manuscript of Jehan Le Begue, 134)

“Take the azure, and put it into a glazed pan; then add some very clean honey and incorporate them well together then grind the honey with the blue upon marble or porphyry until it becomes an almost impalpable powder. When it is ground fine put it back into the pan and wash it several times with warm water, and when it is well washed with warm water, wash it with cold water, and after each time let the azure sink to the bottom. Continue this until it is well washed, cleaned, and purified ; then take the azure and put it to soften in clear and clean ley in a glass vase, such as a tumbler, and let it stand for the space of seven days; change the ley every two or three days, and then wash it well with fresh and clear water, and let it dry in the shade in a place where no dust will get to it” (Bolognese Manuscript, 408)

Further Resources

- The Making and Knowing Project

- Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano, eds. (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020)

- Other recipe books:

- Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook: The Italian “Il Libro Dell’arte”, ed. Daniel V. Thompson (New York: Dover Publications, 2018)

- Mary P. Merrifield, Medieval and Renaissance Treatises on the Arts of Painting: Original Texts with English Translations (New York: Dover, 2003)

- Traveling Scriptorium: A Teaching Kit by the Yale University Library

- CAMEO Characteristics of Common Blue Pigments - very helpful overview: Table with all blue pigments, their composition, usage, characteristics, etc.

- CAMEO links:

- Pigments Through the Ages

- The Color of Art: Pigment Blue, PB (Blues) - Artist’s Paint and Pigments Reference: Color Index Names, Color index Number and Pigment Chemical Composition; Table with info, characteristics, and manufacturers, including references

- Dunkerton - The Materials of a Group of Late Fifteenth-century Florentine Panel Paintings, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/media/15629/dunkerton_roy1996.pdf

- Dunkerton - Titian’s painting technique to c. 1540, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/media/16259/vol-34-essay-1-2013.pdf

- De Keyser - de Heem 1606-1684 - a technical examination of fruit and flower still lifes combining MA-XRF scanning, cross-section analysis and technical historical sources, https://heritagesciencejournal.springeropen.com/counter/pdf/10.1186/s40494-017-0151-4.pdf

- Spring, Higgitt, Saunders - Investigation of Pigment-Medium Interaction Processes in Oil Paint containing Degraded Smalt, http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/technical-bulletin/spring_higgitt_saunders2005

- Spring, Keith - Aelbert Cuyp’s Large Dort - Colour Change and Conservation, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/upload/pdf/spring_keith2009.pdf - Discussion of vivianite, azurite

- Hagadorn - An Investigation into the Use of Blue Copper Pigments in European Early Printed Books, http://cool.conservation-us.org/coolaic/sg/bpg/annual/v23/bp23-07.pdf

- Kirby, Saunders - Fading and Colour Change of Prussian Blue: Methods of Manufacture and the Influence of Extenders, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/media/15510/kirby_saunders2004.pdf

- Marissa Bartz, Gabriela Rosas, Jerome Paquet, and Grace McLean - Non-invasive Technical Analysis of Illuminated Manuscript Leaves from the W.D. Jordan Rare Book and Special Collections, Queen’s University: A Collaborative Project, https://www.culturalheritage.org/docs/default-source/publications/annualmeeting/2022-posters/32-non-invasive-technical-analysis-of-illuminated-manuscript-leaves-from-the-w.d.-jordan-rare-book-and-special-collections-queen's-university-a-collaborative-project---bartz.pdf?sfvrsn=e1af1720_3

- Video of azurite preparation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q9thSoVGfEk

- Video of lapis lazuli preparation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JBzEAt_ynvc