sandbox

The “Sandbox” space makes available a number of resources that utilize and explore the data underlying "Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640" created by the Making and Knowing Project at Columbia University.

Textual Analysis of Instances of “To Know” in Ms. Fr. 640

Beah Jacobson, Fall 2021

On folio 125r of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, the phrase “a sçavoir” appears circled and set off from a stream of surrounding marginal text on plaster; its placement suggests that it may accompany the folio’s “Scimitars” entry. Combined with an auxiliary “a,” this phrase is somewhat more enigmatic than the straightforward English infinitive “to know,” as translated in the Digital Critical Edition of the Making & Knowing Project. Rather, we might take it as a gerund or part of a verbal phrase – something closer to the procedural sense of “for knowing” than “to know.” Did this note in fact refer to the scimitar recipe? If so, what made that particular recipe so worth knowing for the manuscript’s author-practitioner? Does the phrase indicate familiarity with or the need to learn a particular knowledge-set? And what, for the author-practitioner, is the relationship between scimitar-making and knowledge-making?

The 170 folios of Ms. Fr. 640 provide an extraordinary record of late sixteenth-century techniques, materials, experiments, and artisanal processes.1 The manuscript’s “recipes” span a wide variety of subjects: drawing, casting, painting, dyeing, molding, arms and armor, cultivation, preservation, distillation, and much more. Such range makes Ms. Fr. 640 a tantalizing repository of craft and artisanal knowledge at a moment of substantial change in European knowledge production. Ms. Fr. 640 serves as a testament to increasing legitimacy of practice, experience, and experiment as viable and trustworthy sources of knowledge.2

Though the Making & Knowing Project has paid substantial attention to the author-practitioner’s attitudes toward knowledge and knowledge production, less attention has been paid to the textual mechanics of “knowing” itself.3 This essay therefore examines the author-practitioner’s knowledge-making practices through quantitative and qualitative assessment of the verb “to know” and its related forms: “know,” “knowing,” “knew,” “knowledge,” “known,” and “unknown.” In doing so, this project begins to answer the questions broached by that tantalizingly ambiguous “a sçavoir.”

Ms. Fr. 640 has 86 instances of “know” and its variants, three instances of the past tense form “knew,” and two instances of the noun form “knowledge.” (In the original French, these instances are primarily “scavoir” and occasionally “cognoistre.”) This paper will categorize, assess, and analyze these instances across both the pre-existing category tags from the Making & Knowing Project, and using my own breakdown of the ways in which the author-practitioner employs the verb “to know.”

Methodology

First, using the web-based Voyant and Oxygen XML tools, I gathered a data set of these 91 examples and the surrounding text. Next, I cross referenced these strings to the M&K recipe id and category tag(s) for each instance. Analyzing each instance in context, I developed a set of functional groups to describe the operation of similar types of instances. The four instances that seemed not to bear resemblance to any category I have grouped together under “Miscellaneous.” (See Appendix 1 for the complete data set and the spreadsheet with my working data.)

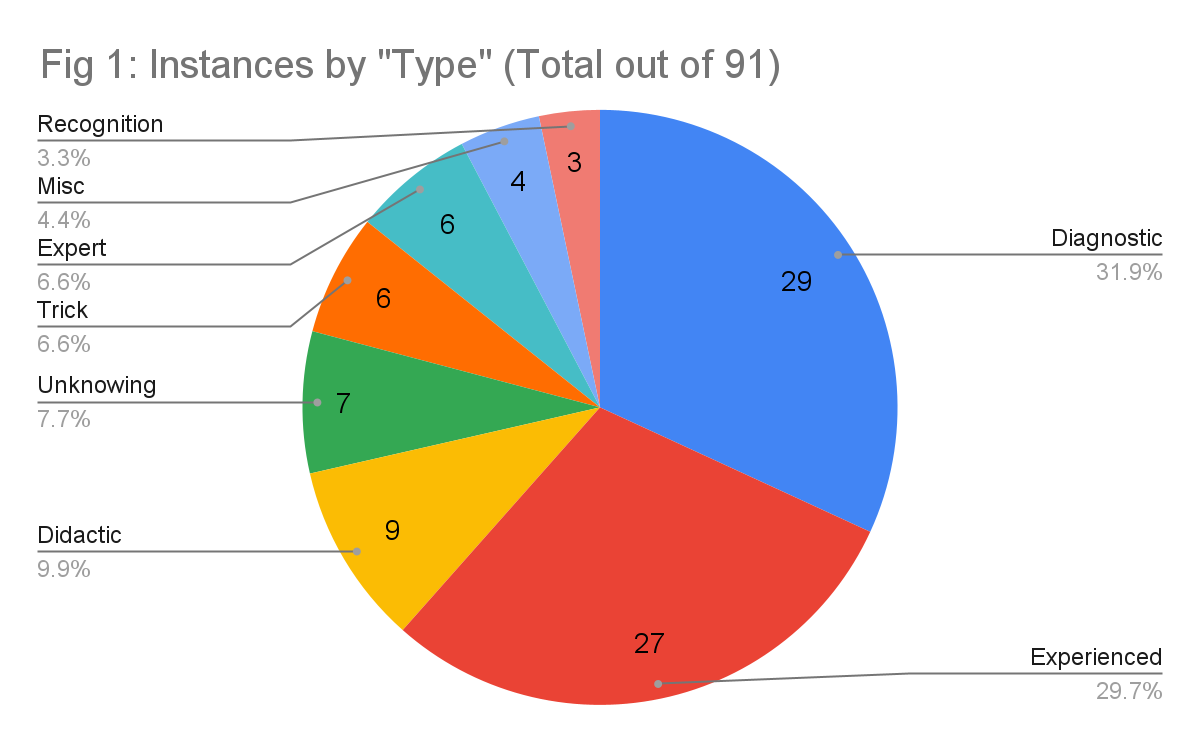

Here is the breakdown by frequency of my “types.” Descriptions and analysis of each category below.

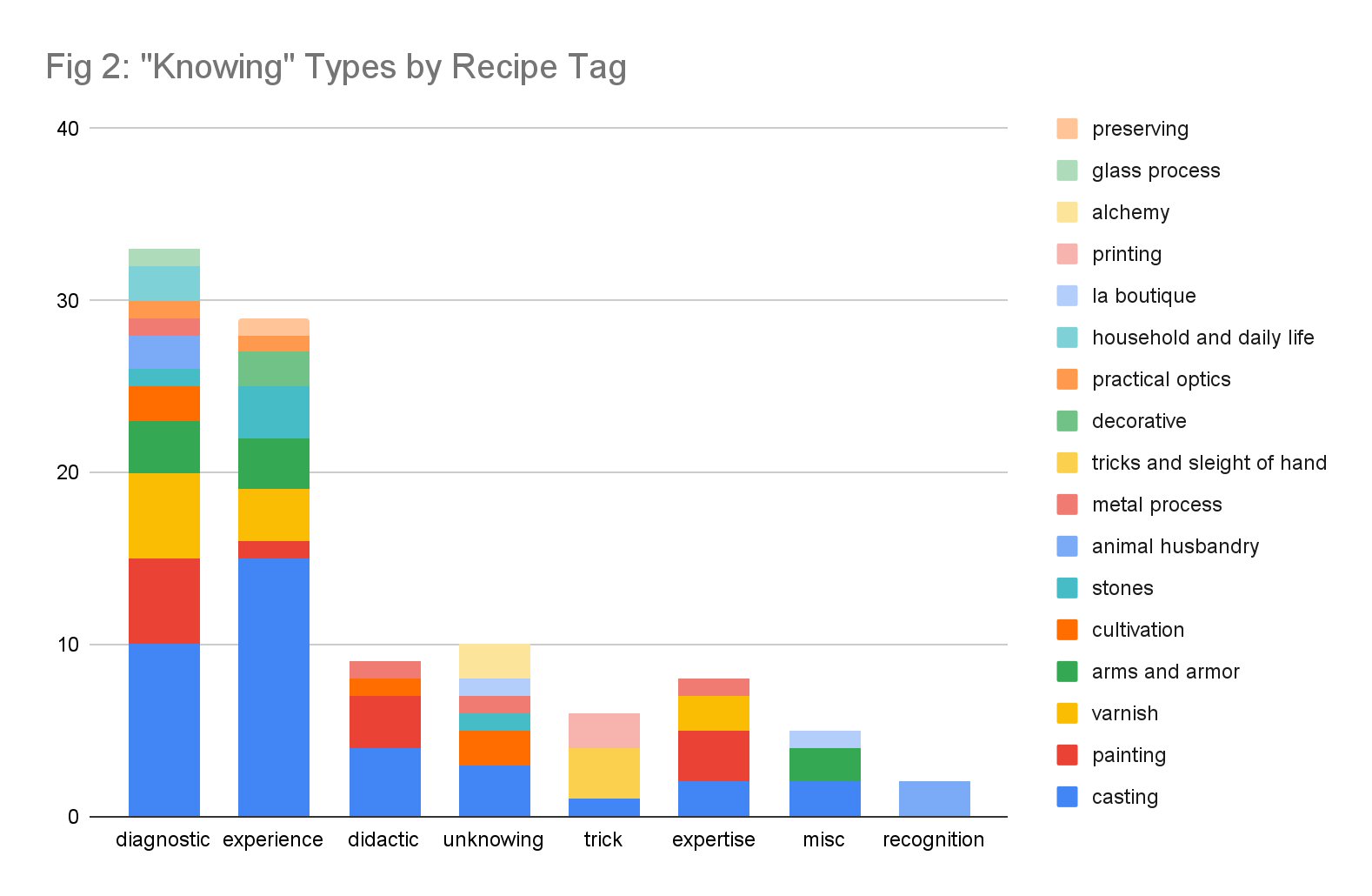

The Making & Knowing Project has already created a set of “category” tags that describe the content and interests of various recipes. I cross referenced these tags with my own breakdown of knowing types to see what categories of recipes make up each knowing type.

For a full data chart, see Appendix 2.

The Diagnostic Know

The diagnostic know refers to instances in which the author-practitioner describes tests for the purposes of gaining information about some substance. Forms in this category include phrases such as “to know if…”, “you will know by…” and “for knowing that…”, and are typically accompanied by description of some action. The diagnostic know is the manuscript’s most prevalent form of the verb “to know.”

Within this group, the recipe tags that appear most frequently are casting, painting, and varnish. Though casting takes up the most real estate here, it is not actually overrepresented when compared to its frequency across the manuscript itself. 34% of recipes in Ms. Fr. 640 are tagged as casting, and 34.4% of recipes within the diagnostic know are tagged as casting.4 Painting (14.3% of Ms. Fr. 640 recipes) and varnish (4.8% of Ms. Fr. 640 recipes) are both overrepresented in this category, each at 17.24 percent of the diagnostic know bucket.

For a full chart of recipe tags as percentages of total recipes within each type, see Appendix 3.

Example

For knowing the good cendrée of azure for oil, 13r:

“The one that accumulates in small clods and is lumpy is the best because it is the most subtle. Also the one that is very pale in color, because oil darkens it. Certain sophisticators mix them, but you will know this if you pour some onto a piece of paper & press it & spread it with the finger since, if it is mixed, it will be found variegated & as if striped with a pale one & a darker one, but if it is unmixed it will be even & of one color.”

“For knowing” and “you will know this if” are excellent examples of the diagnostic know. This formulation uses “know” to express some qualitative demarcation of materials or recipe stage. This “know” therefore directly connects knowledge acquisition to artisanal experience. Here, knowledge is learned and gained through an explicit, hands-on interaction with a material.

The Experienced Know

The most prevalent usage in this category is the famous “as you know” construction (always “comme tu sçais” in French), along with the occasional “you know how” and “that you know” sprinkled in. I term this the experienced know because such instances imply assumed familiarity and experience. Where, when, and why might the author-practitioner assume his reader (the “you” of the entry) to have some prior knowledge of the processes described in the manuscript? Does this formulation occur most frequently in certain types of recipes? Do certain instances refer back to particular entries?

As Fig. 2 demonstrates, by far the most common recipe tag for this type of “know” is casting. In fact, though casting only makes up 34% of the recipes in the manuscript, it describes a whopping 55% of instances (15 tags out of 27 different recipes).5 Such overrepresentation suggests a higher degree of familiarity or “experience” with casting from the author-practitioner, and perhaps a higher expectation of familiarity amongst his readers. Varnish, arms and armor, and stones are the next most common tags for recipes that use “know” to assume some degree of experience.

Example

Counterfeit Jasper recipe, 10r: “You know how, with scrapings of the said horn, roses can be imitated.”

This instance appears to gesture toward another recipe. Also on 10r, the author-practitioner instructs readers to use shaved horn scrapings to imitate the translucency and delicacy of rose petals: “These are counterfeited either with the scrapings of horn used for lanterns, or with scrapings of parchment, very clear & delicate & dyed & employed as you know.”

This later “as you know,” the second such instance of “the experienced know” on the recto, then appears to be curiously self referential. Does the reader already know how to shave horn into rose petals because of the earlier suggestion on the page? Or is there an assumption of familiarity that underlies both references?

The Didactic Know

The didactic know occurs in instances in which the author-practitioner deploys the verb in a teacherly (and authoritarian) manner. I.e., “you must know X, and then you can do Y,” or “once you know X, you will be able to…” These instances are often in the imperative mood, and refer to knowledge that should be learned, gained, or taught.

Example

Orange Trees, 90r: “And know that, for this effect, it would be better to join the sides of the cases with screws & not with nails…”

I term instances like this the didactic know because they fulfill a teacherly function. Here is a thing that should be known in order to achieve some desired outcome. Typically, these instances present as imperative and moralizing about the effect of these formulations.

The Unknowing Know

This locution refers to what is not yet known or what cannot be known, most prevalently with the author-practitioner as the subject. “I do not know if” occurs four times in the manuscript. In each of these cases, the topic is knowledge-in-production, describing experimental processes and outcomes.

Interestingly, recipe tags for the unknowing know span casting, cultivation, alchemy, stones, and metal process.

Example

Whitening Enilanroc, 13r: “I do not know if it would be better to reheat it under hot ashes, & if it would be good to encase it in alabaster, which is very cold, as I encased it in the brick.”

These instances typically recognize the limitations of the author-practitioner’s experimental knowledge. In this instance, the author-practitioner recounts his own experimental process in the first person. This moment occurs at the end of the recipe, when he explains that he has not tried this process in other ways. Importantly, then, this “I do not know” signifies an ongoing process of experimental trial, rather than unknowability itself.

The Expert Know

The expert know refers to a specific individual or group of individuals with some mastery of some subject. I also include in this category instances in which expertise is affirmed as secret, exceptional knowledge of a particular craft.

Examples

Painter, 32r: “The one who knows to work well in distemper will work well in oil.”

and:

Painting Esmail D’azur in Oil, 11r: “This is a secret that is hardly known to common painters.”

Though this litotes (“hardly known”) might seem to belong in the unknowing bucket, I group it in expert for two reasons. First, it refers to knowledge that can be and is known. Second, the absence of that knowledge in some individuals serves to elevate other individuals (such as the author-practitioner) who do have it.

The Trick Know

Unlike the unknowing know, this locution pattern describes intentional modes of knowing, unknowing, or revelation of some fact for the purposes of joking, tricking, or subterfuge. The trick know plays with knowledge, deliberately misrepresenting, obfuscating, and occasionally revealing what is or what can be known. These formulations bring the reader into a privileged, ingroup understanding with the author-practitioner.

Example:

For telling someone that you will teach him something he does not know, and neither do you., 35r: “Take a string or a small stick and take the measurement from the tip of his ear to the tip of his nose and show it to him. Thus you will teach him something you did not know, and neither did he.”

Also occurring in da Vinci’s Codex Atlanticus, this particular joke links humor and entertainment with broader epistemological questions around knowability and unknowability.6

Know of Recognition

This pattern refers to the familiar relationship between individuals, and how they recognize one another. Interestingly, two of these three instances fall into the “animal husbandry” category, referring to birds and horses.

Example

1r: “Mestre Jehan Cousin, who resides in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, knows of the master.”

For making a horse follow, 54v: “One needs to give it sweet bread & it will know the one who will do him such good.”

Miscellaneous Uses

I could not resolve the following uses reasonably or meaningfully into any of these other categories:

Chimolée, 12r: “The terre chimolée, otherwise known as fuller’s earth…”

I set this individual usage apart because “known” here is an artifact of the translation. The French version uses “aultrement des parayres…” and no particular instantiation of either scavoir or cognoistre.

24v: “Know the magazines of France for the artillery”

This phrase occurs as a marginal note, clearly aligned in some way with the military recipes surrounding it. As an imperative (“scaches” in French), this phrase seems to suggest that it is information that ought to be known. Within the context of this compendium, however, it is not precisely didactic because it does not contain any additional explanation or development, nor does it signal teaching and learning. Is this a note from the author-practitioner to himself? An interest in developing this topic further? Advice to the reader not unlike a modern note to reference or compare?

Scimitars, 125r: “A sçavoir” circled and set off by itself in the margin.

For the workshop, 166r: “In order to publish them for those who do not know them; so that as the preceding day is teacher for the subsequent, thus you needed to learn from those who preceded you in order to teach to those who come after. The Latins took from the Greeks, as Cicero from Plato & Vergil from Homer… Will one not say the weaver has made a cloth or precious stuff, even though he did not dye & twist, wind & prepare the bobbins and balls of thread?”

This remarkable passage describes the manuscript itself, and the author-practitioner’s intention to gather and disseminate knowledge that has been accumulated not only through his own experience, but through the lessons of centuries of knowledge-makers. Importantly, the author-practitioner here sets on par the knowledge of the ancients and the knowledge of modern artisans. He imagines one holistic thread of transmission, inheritance, practice, and re-transmission, in which Ms. Fr. 640 participates.

Further Opportunities for Analysis

The textual analysis of “to know” suggests several possible avenues for future study. Such projects might compare the differential deployment of the French verbs “sçavoir” and “cognoistre” (alone and with respect to contemporary texts); analyze the frequency of different recipe tags across other verbal constructions; develop different systems to categorize forms of knowing. These and other projects will help develop a richer understanding of the author-practitioner’s own attitudes toward and experiences with knowledge-production, as well contribute to discussion of the period more broadly.

Appendix 1: Instances of “know” in Ms. Fr. 640

| Folio | Recipe | Type of Know | Recipe Tag |

|---|---|---|---|

| 001r | N/A | Recognition | List Of Names |

| 003v | Thick varnish for planks | Experience | Varnish |

| 004r | Varnish of spike lavender oil | Diagnostic | Varnish |

| 008r | For making a breach in a wall by night | Experience | Arms and Armor |

| 008v | Perfect amalgam | Experience | Casting |

| 009r | Plowman | Diagnostic | Cultivation |

| 009r | Merchant | Diagnostic | Merchants |

| 010r | Counterfeit jasper | Experience | Stones; Decorative |

| 010r | Roses | Experience | Decorative |

| 011r | Painting esmail d’azur in oil | Expertise | Painting |

| 012r | Chimolée | Misc | Casting |

| 013r | For whitening enilanroc | Unknowing | Stones |

| 013v | For knowing the good cendrée of azure for oil | Diagnostic | Painting |

| 013v | For knowing the good cendrée of azure for oil | Diagnostic | Painting |

| 019v | Mathematical figures without ruler and compass | Experience | Painting |

| 021r | For firing a cannon at night | Experience | Arms and Armor; Practical Optics |

| 024r | Grenades | Diagnostic | Arms and Armor |

| 024v | For bringing a cannon over land | Misc | Arms and Armor |

| 031v | Painting on glass | Diagnostic | Painting; Glass Process |

| 032r | Painter | Expertise | Painting; Varnish |

| 032r | Painter | Expertise | Painting; Varnish |

| 034r | Writing cunningly | Trick | Tricks and Sleight Of Hand |

| 035r | For telling someone that you will show teach him something he does not know, and neither do you | Trick | Tricks and Sleight Of Hand |

| 035r | For telling someone that you will show teach him something he does not know, and neither do you | Trick | Tricks and Sleight Of Hand |

| 038r | Amber | Experience | Stones |

| 039r | Goldsmith | Unknowing | Casting; Metal Process |

| 039r | Pastel woad | Diagnostic | Dyeing |

| 049v | Birds | Diagnostic | Animal Husbandry |

| 051r | Counterproofing | Trick | Printing |

| 051r | Counterproofing | Trick | Printing |

| 052r | The work done in Algiers | Unknowing | Cultivation; Alchemy |

| 052r | The work done in Algiers | Unknowing | Cultivation; Alchemy |

| 054r | Silkworms | Diagnostic | Cultivation; Animal Husbandry |

| 054v | For making a horse follow | Recognition | Animal Husbandry |

| 055r | For firing a schioppo senza rumore | Experience | Arms and Armor |

| 055v | For knowing the course one takes on the open sea | Diagnostic | Household and Daily Life |

| 056r | Varnish for distemper | Experience | Varnish |

| 059r | Azure | Diagnostic | Varnish; Painting |

| 060v | Varnish dry in an hour | Diagnostic | Varnish |

| 062r | Perspectives | Didactic | Painting |

| 062v | Perspective | Diagnostic | Painting |

| 064v | Apprenticeship of the painter | Didactic | Painting |

| 065r | Flesh color | Didactic | Painting |

| 068v | Casting | Diagnostic | Casting |

| 070r | Sand | Trick | Casting |

| 071r | Mulled and sugared wine | Diagnostic | Household and Daily Life |

| 072v | Casting | Diagnostic | Casting |

| 082v | Method of casting in bronze | Experience | Casting |

| 085r | Sand for lead, the most excellent of all, for high and low reliefs | Experience | Casting |

| 085r | Sand for lead, the most excellent of all, for high and low reliefs | Diagnostic | Casting |

| 086r | Experimented sands | Unknowing | Casting |

| 087r | Excellent sand for lead, tin, and copper | Diagnostic | Casting |

| 088r | Varnish | Diagnostic | Varnish |

| 090v | Orange trees | Didactic | Cultivation |

| 091v | Molding with cuttlefish bone | Diagnostic | Casting |

| 095r | Furbisher | Diagnostic | Arms and Armor |

| 097r | Gilding | Diagnostic | Arms and Armor; Metal Process |

| 097v | Mastic varnish dry in a half hour | Experience | Varnish |

| 097v | Mastic varnish dry in a half hour | Diagnostic | Varnish |

| 098v | Birds | Recognition | Animal Husbandry |

| 099r | Founding | Experience | Casting |

| 100v | Gemstones | Experience | Stones |

| 104v | Goldsmith | Didactic | Metal Process |

| 107r | Plaster | Diagnostic | Casting |

| 107v | Plaster | Didactic | Casting |

| 111r | Clay earth | Experience | Casting |

| 112r | Putting to death the animal for molding | Diagnostic | Casting |

| 114r | Second cast | Experience | Casting |

| 120r | Sand for casting in gold | Expertise | Casting |

| 121r | Keeping dry flowers in the same state all year | Experience | Preserving |

| 121v | Silver for casting | Expertise | Casting |

| 123r | A means di far correr lotnegra | Expertise | Metal Process |

| 125r | Plaster | Didactic | Casting |

| 125r | Scimitars | Misc | Arms and Armor;Casting |

| 125v | Plaster for casting of wax | Didactic | Casting |

| 126r | Molding fruits and animals in sugar | Experience | Casting |

| 129r | Viper color | Experience | Casting |

| 129v | Spider molded on a leaf | Experience | Casting |

| 130v | Molding a crab | Didactic | Casting |

| 131v | When the cast of tin or lead becomes porous | Diagnostic | Casting |

| 135r | Vine leaf and small frog | Experience | Casting |

| 140v | For casting in sulfur | Experience | Casting |

| 145r | Cuttlefish bone | Diagnostic | Casting |

| 149v | Bat | Experience | Casting |

| 153r | Molding hollow for seals or other things | Experience | Casting |

| 156r | Molding promptly and reducing a hollow form to a relief | Experience | Casting |

| 156v | Molding a fly | Experience | Casting |

| 157r | Arranging plants or flowers for casting | Diagnostic | Casting |

| 160r | Press for large molds | Unknowing | Casting |

| 166r | For the workshop | Unknowing | La Boutique |

| 166r | For the workshop | Misc | La Boutique |

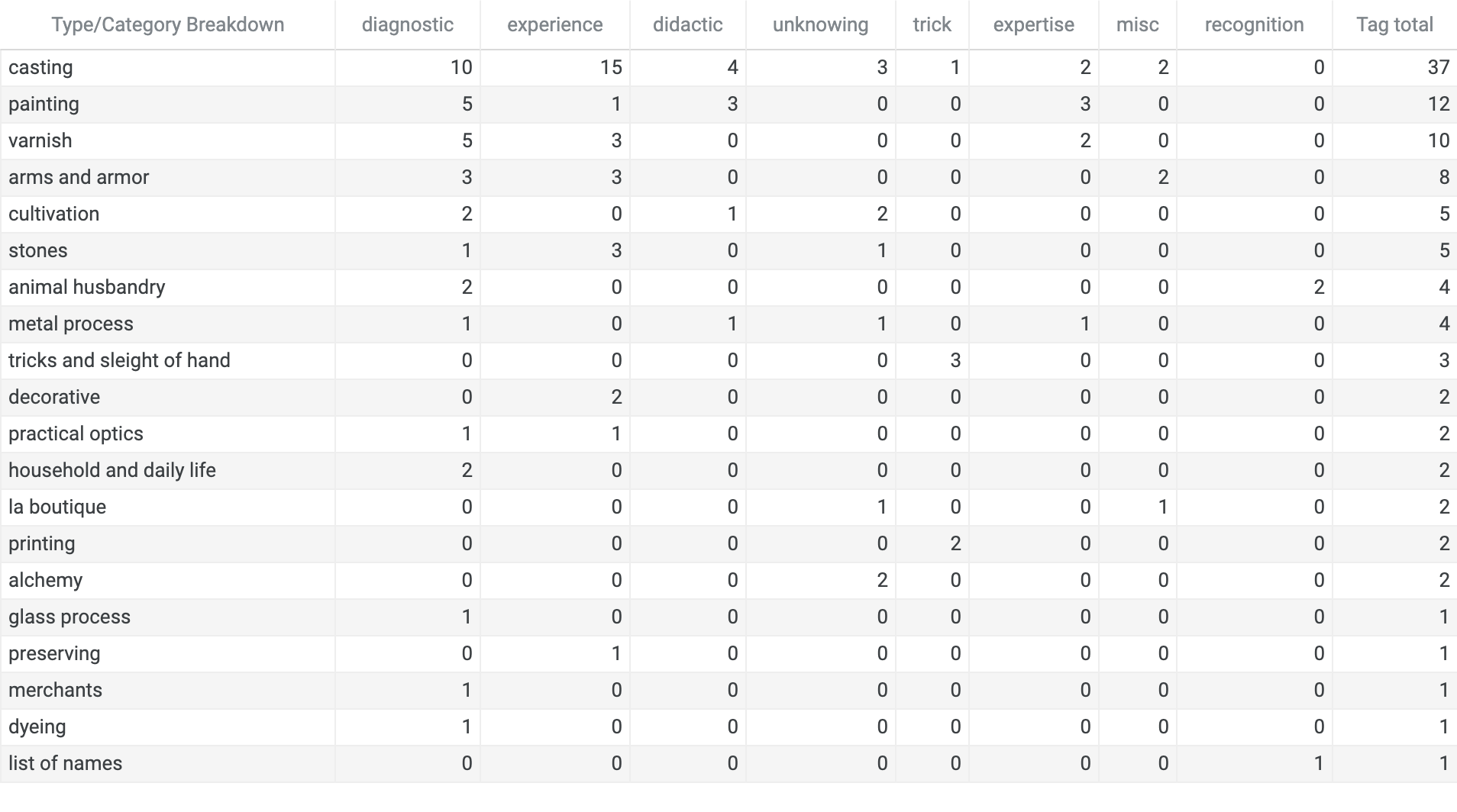

Appendix 2: Number of recipe tags within each type of “knowing”

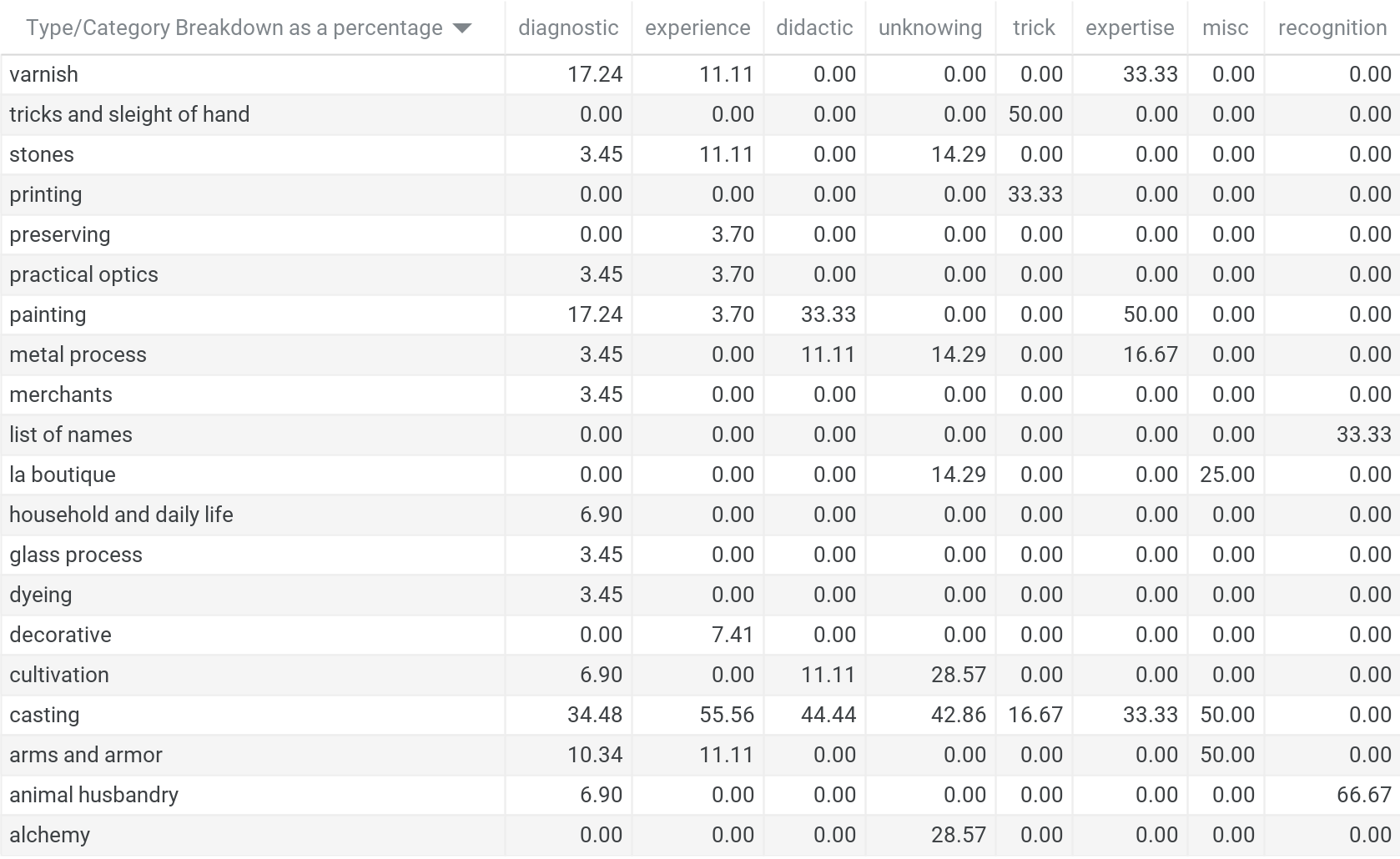

Appendix 3. Recipe tags as a percentage of total recipes within each type of “knowing”

Note: This data is most meaningful for the diagnostic and experienced types because those have the most instances (29 and 27, respectively). Conversely, because individual instances within the miscellaneous type are discrete, percentages of recipes within this bucket are least meaningful.

Bibliography

Barwich, Ann-Sophie. “Sleight of Hand Tricks.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_043_sp_16. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/rfq6-0k88.

Rosenkranz, Naomi. “Understanding and Analyzing the Categories of the Entries in BnF Ms. Fr. 640,” Making and Knowing Sandbox, 2021. https://cu-mkp.github.io/sandbox/docs/categories.html

Keller, Vera. “’Everything Depends Upon the Trial (Le tout gist à l’essay)’: Four Manuscripts Between the Recipe and the Experimental Essay.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_320_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/vj69-8h20

Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano, eds., Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640 (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020), https://edition640.makingandknowing.org

Smith, Pamela H. “An Introduction to Ms. Fr. 640 and its Author-Practitioner.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_300_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/ny3t-qg71

Taape, Tillmann. “’Experience Will Teach You’: Recording, Testing, Knowing, and the Language of Experience in Ms. Fr. 640.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_303_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/njnq-6q58.

-

Making and Knowing Project, Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, https://edition640.makingandknowing.org. ↩

-

Keller (2020). ↩

-

See, for instance, Taape (2020) for an excellent breakdown of the manuscript’s terms experience, experimenter, essayer, esprouver, and cognoistre. ↩

-

Data for recipe tag frequency across the manuscript as a whole are found in the M&K Sandbox. ↩

-

For frequency and tag distribution throughout the manuscript, see “Understanding and Analyzing the Categories of the Entries in BnF Ms. Fr. 640” in the Making and Knowing Sandbox. ↩

-

For more on tricks and sleight of hand, see Barwich (2020). ↩