sandbox

The “Sandbox” space makes available a number of resources that utilize and explore the data underlying "Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640" created by the Making and Knowing Project at Columbia University.

Understanding and Analyzing the Categories of the Entries in BnF Ms. Fr. 640

Naomi Rosenkranz, Assistant Director, The Making and Knowing Project

[Last updated 2021-11-08]

The anonymous, 16th-century artisanal manuscript, BnF Ms. Fr. 640, is comprised of almost 1,000 “entries.” In the Making and Knowing Project’s Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, an entry is a unit of text under a title. These include instructions, recipes, descriptions, and observations on a wide range of topics, including casting, painting, and medicine.

Each entry has been grouped into at least one (and up to three) descriptive categories. These are attributes of each entry <div>, and can be extracted from the xml of the manuscript pages.

For example,

<div id="p004v_1" categories="varnish;arms and armor">for the entry on fol. 4v, “Black varnish for sword guard, bands for trunks, &c”

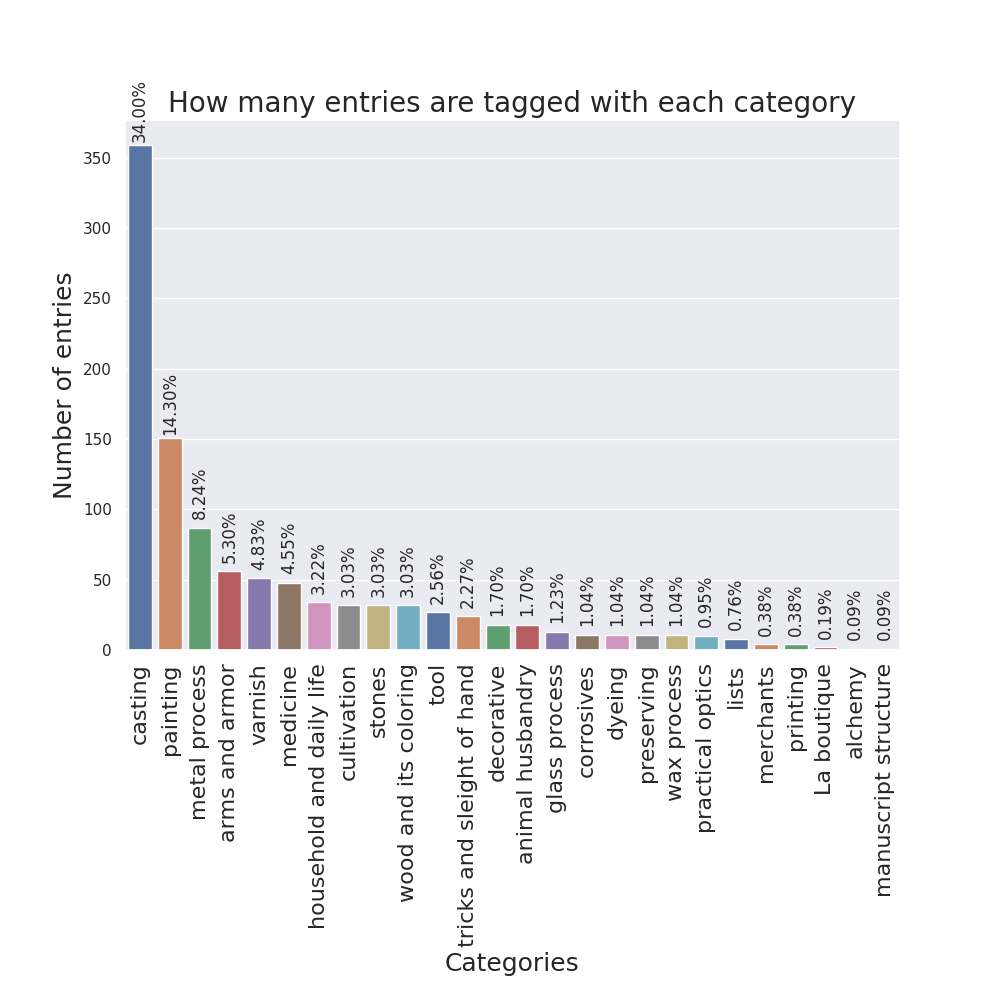

Percentage of Entries by Category

As can be seen by the bar graph below, “casting” by far has the most entries of any category, followed by “painting” and then “metal process.”

Raw Data and Generation

This plot is generated by manuscript_visualizations.py developed by Roni Kaufman in summer 2020 using underlying workflows in cu-mkp/manuscript-object.

The raw data (the xml-encoded transcriptions and translations of the manuscript text) is found in cu-mkp/m-k-manuscript-data/ms-xml. See also the extracted elements and properties in cu-mkp/m-k-manuscript-data/metadata/entry-metadata.csv.

Why is This Interesting?

- Casting: A large majority of casting recipes supports the theory that this is the author-practitioner’s main focus and area of expertise. The casting entries are some of the longest and seen to contain the most first-hand observations and active experimentation.

- From fol. 80v to 93r is an almost uninterrupted cluster of entries discussing the author-practitioner’s first-hand experiments with sands and other molding materials for casting.

- For example, see fol. 84v-85r, “Sand for lead, the most excellent of all, for high and low reliefs”, in which he records multiple trials, failures, and successes. The best method? Mix ceruse (lead carbonate) with egg white into the sand and oil the mold lightly with walnut oil.

- Interested in failure? Check out this video of Project Postdoc Tianna Uchacz discussing this further:

- Alchemy: While the manuscript was originally thought to contain alchemical writings, as was common for many “Books of Secrets” in the Renaissance that contained first-hand experimentation, the distribution of categories shows that “alchemy” is one of the least prevalent categories. In fact, there is only one entry that is “alchemical”: fol. 52r, “The work done in Algiers”

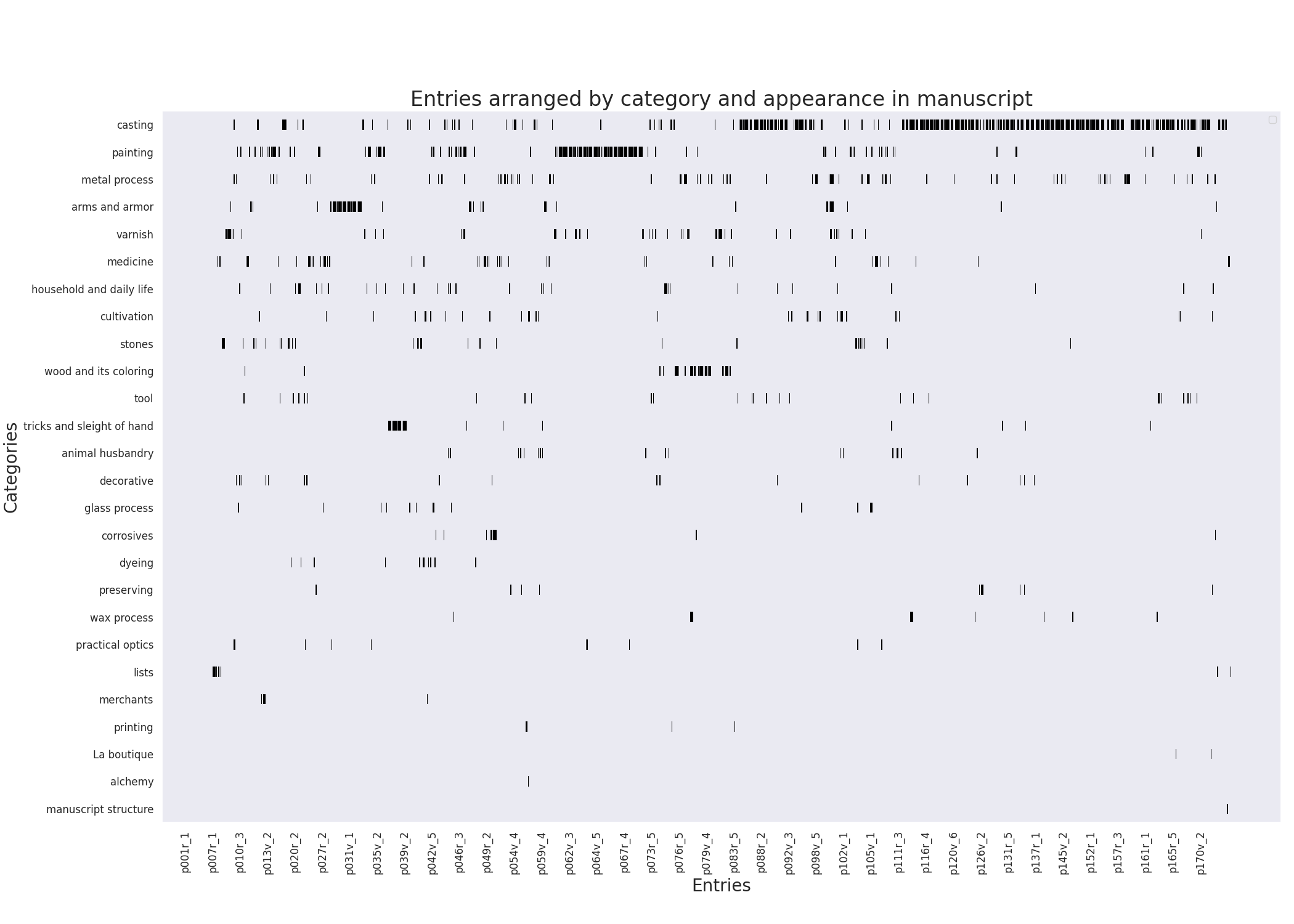

Distribution of Entry Categories Across the Folios

The manuscript is composed of 170 folios which is 340 pages:

1 folio = front page and back page

The first folio is 1r (recto = front) and 1v (verso = back), the second is 2r and 2v, then 3r, 3v, etc.

Starting at the beginning of the manuscript on 1r and ending with the last page, 170v, each entry is plotted below by category. This shows us the distribution of the entry categories across the entire manuscript.

One black vertical line = 1 entry.

Why is This Interesting?

Casting and Painting Clusters: Is the Author-Practitioner a Metalworker?

- Casting, the largest category, is found throughout the entire manuscript, but clustering of entries can be seen in the second half, especially around the 90s and after fol. 115r or so.

- Good molds rely on good sands (or earths), according to the author-practitioner. Like modern-day plaster, these sands (often mixed with a liquid binder) form the hollow mold into which molten metal, wax, or sulfur can be poured to create a cast object.

- He recommends a number of additivies to the sands, including:

- Painting entries appear earlier in the manuscript, with a distinct cluster of entries around the 60s. This seems to start with fol. 56v, “Painter,” a relatively long entry which covers a wide variety of topics:

- pigments: “Vermilion ground by itself is wan and pale”

- binding media: “In distemper do not mix your different colors together”

- tools: “For palettes to paint, ivory is excellent”

- geographical practices: “The Italians soften by hatching with a large flattened paintbrush”

- There is a section which appears in the continuation of this entry on fol. 57r that may provide further evidence that the author-practitioner’s main focus, or perhaps his main area of expertise, is casting. Even in an entry about various painting techniques and materials, he draws immediate connection back to casting (bold has been added for emphasis and does not appear in the original):

“…Lake takes long to dry in oil and for that reason one must grind some glass with it. But one needs to choose cristallin because it is cleaner. And because it would be too difficult to grind by itself, one must redden it on the fire, then when entirely red throw it into cold water, & it will crumble & pulverize easily for grinding it afterward. Being well ground it with a lot of water, it resembles ground lead white, but for all this it has no body. I think it would be good for casting.”

- The clustering of painting entries also corresponds to a section with very few casting entries. Perhaps this is a general trend?

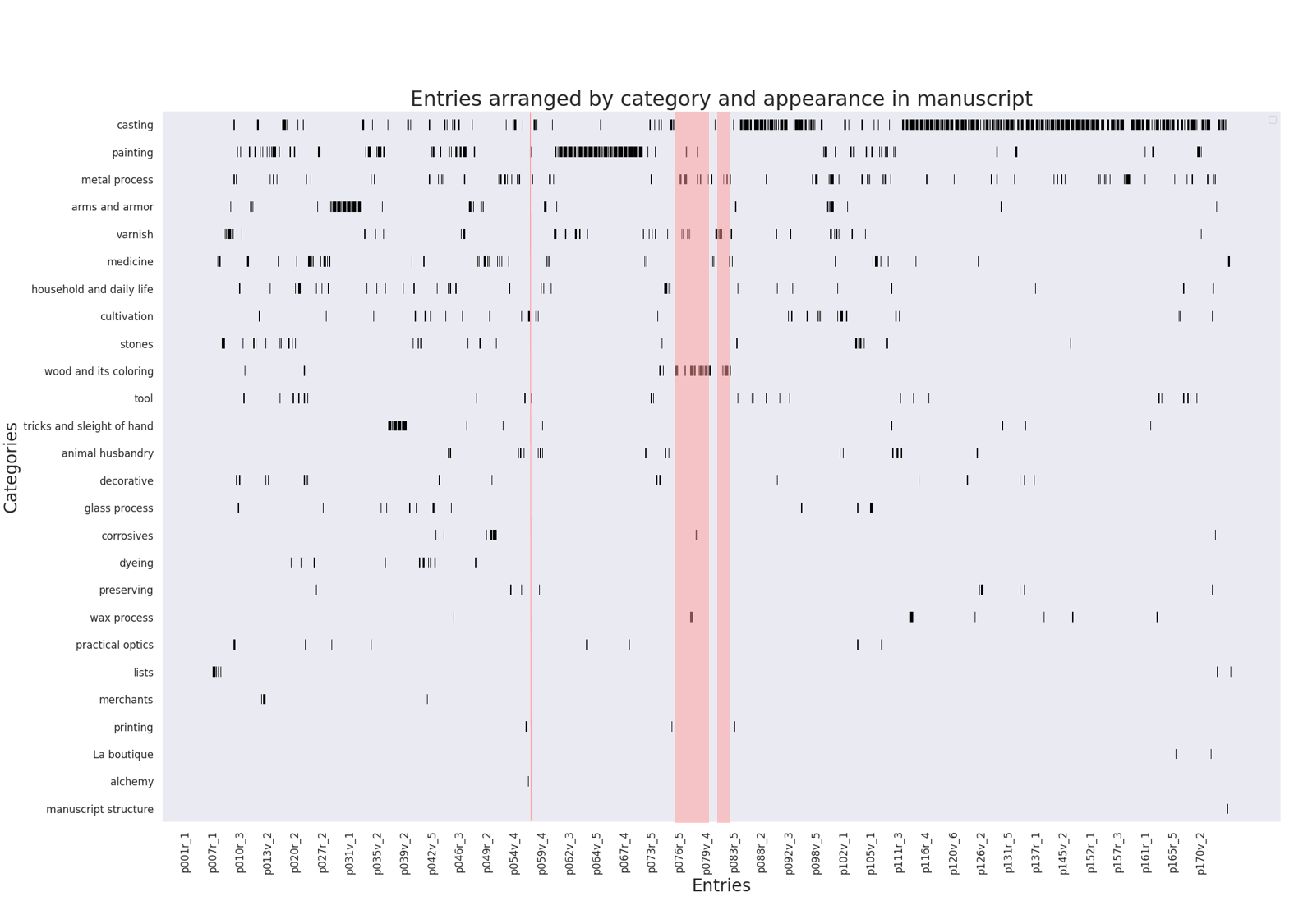

Use of a Scribe?

While the great majority of the manuscript is written in one hand, there are a few instances of a different hand, including a number of sequential entries that begin on fol. 73r and end on fol. 76v. The writing here is a semi-calligraphic French script and is most likely that of a scribe. The same hand appears again in a series of entries from fol. 57r to fol. 58r and from fol. 77r to fol. 79v.

The sections are highlighted below in red.

Why is This Interesting?

Categories of the Scribe’s Entries

These sections show that the author-practitioner may have employed a scribe to assist him in the gathering and recording of entries.

The types of entries written by the scribe all fall within the same few categories, highlighted below in blue.

The categories by section:

| Category | # entries |

|---|---|

| painting | 2 |

| varnish | 1 |

| arms and armor | 1 |

| Category | # entries |

|---|---|

| wood and its coloring | 22 |

| metal process | 9 |

| varnish | 5 |

| wax process | 3 |

| painting | 2 |

| corrosives | 1 |

| Category | # entries |

|---|---|

| wood and its coloring | 6 |

| varnish | 8 |

| metal process | 3 |

| medicine | 1 |

- One category that seems to dominate is “wood and its coloring.” Of the 32 entries in this category, 28 are written by the scribe - that’s 87.5% of the category! Thus, the author-practitioner only wrote 4 of the entries treating this topic.

- Notably, there are no entries categorized as “casting,” the author-practitioner’s main concern throughout the manuscript.

- Want to do further analysis on these entries?

- Use/download this [CSV of scribe entry-metadata]

- Explore the List of Entries resource in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France.

Evidence of the Scribe’s Work

What clues in the text do we see to support the theory that the author-practitioner was working together with a scribe?

- One example is an intervention on fol. 73r. In the entry, moullée (grindings) is added in a hand that is most likely the author-practitioner’s, to fill in a blank left by the scribe who wrote the rest of the page.

- There is also evidence of dictation: perhaps the author-practitioner spoke out loud to the scribe who wrote his notes down. In multiple entries on fols. 77v, 78r, and 79v, the scribe seems to have been confused by the word “sandarac,” a type of resin used commonly in varnish recipes. He writes down words that sound similar, such as sang (blood) de Drac (of the dragon) or da Rac (the devil’s shout), before ultimately correcting them.

- In a longer entry that begins on fol. 56v, “Painter,” the author-practitioner composes most of the entry, but a few sections in the middle are written by the scribe. Perhaps they were taking turns writing things down? Or writing at different times, adding to each other’s sections?

Painting and Varnish Entries

We often closely associate varnish recipes with painting recipes in the Renaissance. For example, in Cennino Cennini’s The Craftsman’s Handbook, ‘Il Libro dell’Arte’, trans. by Daniel Thompson (New York: Dover, 1960), information about varnish follow the sections on painting.

Cennini’s Painting Sections

- “II: The second section of this book: brining you to the working up of the colors”

- “III: The method and system for working on a wall, that is, in fresco”

- “IV: How to paint in oil on a wall, on panel, on iron, and where you please”

- “V: The system by which you should prepare to acquire the skill to work on panel”

- “VI: How you should start to work on panel or anconas”

Cennini’s Varnish Section

- “Introduction to a short section on varnishing”

- “When to varnish”

- “How to apply varnish”

- “How to make a painting look as if it were varnished”

Varnishing was often the final step in the creation of the painting, covering the layers of (usually) oil paint with a layer of varnish to help protect the paint underneath or to enhance the optical effect of the painting. Many painting treatises of this period include recipes for varnishes alongside pigment recipes and descriptions of painting techniques.

Cennini even notes that when you varnish your paintings or your colors more generally,

“they then become very fresh and beautiful, and remain in pristine state forever.” pg. 99 (Thompson, 1960)

Painting and Varnish in Fr. 640

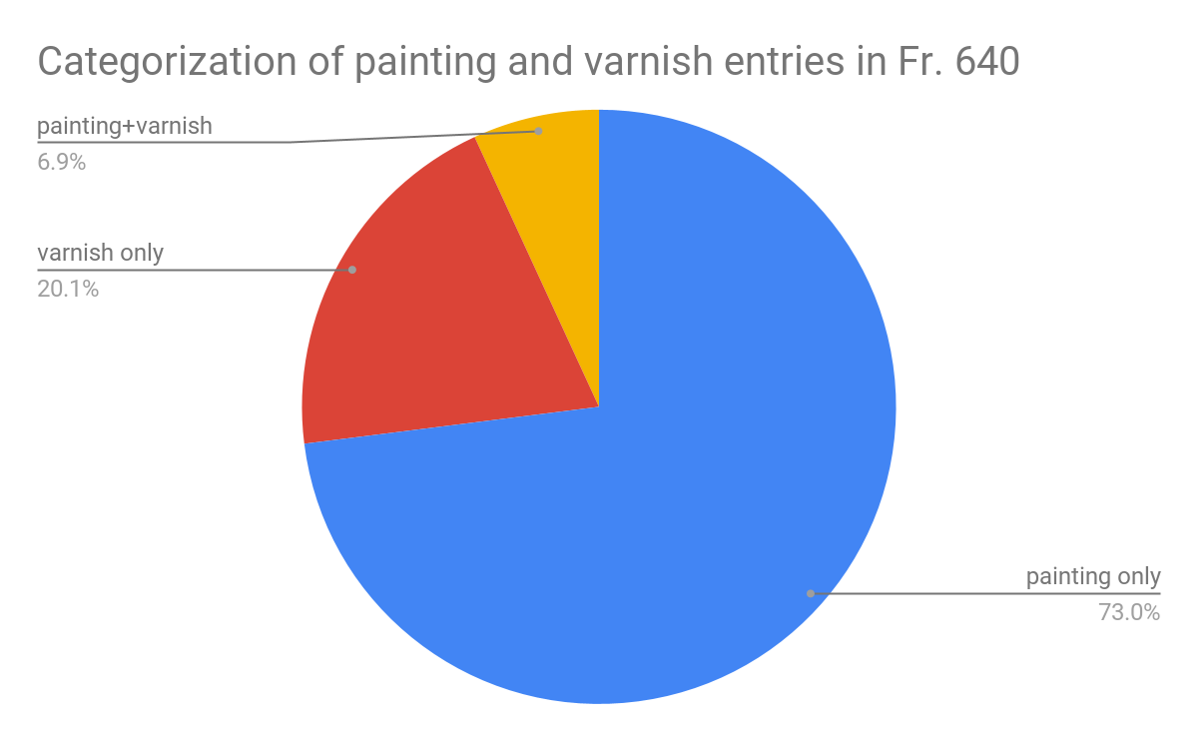

In BnF Ms. Fr. 640, there are 189 entries categorized as “painting,” “varnish,” or both “painting” and “varnish.” They account for approximately 13% of all entries in the manuscript.

| Category | # entries |

|---|---|

| painting only | 138 |

| varnish only | 38 |

| painting AND varnish | 13 |

| TOTAL | 189 |

The above pie chart was created using:

- The raw data in entry_metadata_paint-varnish_data.csv

- The calculations based upon that data in entry_metadata_paint-varnish_analysis.csv

- The processing and workup were done using Microsoft Excel, in an Excel spreadsheet, entry_metadata_paint-varnish.xlsx

You can use and/or download this data to do your own analysis!

Why is This Interesting?

Might we expect there to be more or less overlap between the two categories?

To ponder this question, it may help to consider the 13 entries categorized as both “painting” and “varnish”:

- fol. 7r, “For coloring stamped trunks”

- fol. 32r, “Painter”

- fol. 42v, “White varnish on plaster”

- fol. 43r, “Purple”

- fol. 43r, “White bronzing”

- fol. 56v, “Painter”

- fol. 59r, “Shadows”

- fol. 60r, “Oil”

- fol. 60v, “Wood color”

- fol. 61v, “Frames of the Germans”

- fol. 66r, “Colors in oil that are imbibed”

- fol. 67v, “Essential oils”

- fol. 165r, “Dragon’s blood”

Fol. 32r, “Painter,” makes a similar point to Cennini about preserving the painting by applying varnish, and then makes a notes about the skills required for working with two different binding media, oil and distemper (glue).

As soon as the colors of panels are well dried, the Flemish varnish them so they do not die any more than they already have & remain in that state.

The one who knows to work well in distemper will work well in oil. But, on the contrary, the one who knows how to work well in oil will not work in distemper.

The other entry titled “Painter” on fol. 56v lists a number of notes about different techniques and paints, and also includes a note about varnishing, suggesting that these notes are all connected in some larger way (treating the same topic). “Shadows” (Fol. 59r), “Wood color” (fol. 60v), and “Dragon’s blood” (fol. 165r) do the same thing: they discuss applying varnish as the last layer on top of paint.

A few entries do not follow this pattern. Instead, they dictate using painter’s ingredients (here, painter’s distemper glue) and then applying varnish, as seen in fol. 42v “White varnish on plaster”, fol. 43r “Purple,” and “White bronzing.” Nonetheless, they seem to suggest using the layering of painter’s glue and varnish to create a certain optical effect, as one would for painting.

Two recipes suggest using varnish as the binding media to create the paint rather than distemper glue or oil on its own: fol. 7r, “For coloring stamped trunks,” and fol. 67v, “Essential oils.”

Because oil is used as a painting medium and as an ingredient in varnishes, “Oil” on fol. 60r discusses the properties that would be suitable for each application:

Walnut oil extracted like peeled almonds is very white. The one of palmachristi. And when the oil has a little body, the colors soften in it. For if the oil is too clear, the colors run & do not have bond, even those that hardly have any body. Fatty oil that is not easily imbibed is appropriate for varnish. The oil is desiccative enough when it dries out as quickly as common varnish.

In “Colors in oil that are imbibed” on fol. 66r, the author-practitioner even offers a way to remedy paint in “fatty” oil with varnish:

It is best that colors in oil are imbibed, that is to say they do not remain shiny after they are dry, for they do not die. But if in some places they are shiny, it is that the fattiness of the oil has remained in that part, which would make the colors die. The varnish mends all this & unites & renders it similar in one place as in another.