sandbox

The “Sandbox” space makes available a number of resources that utilize and explore the data underlying "Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640" created by the Making and Knowing Project at Columbia University.

Dyeing with Onion Skins

Annika Cunningham, summer and fall 2021

Introduction

My name is Annika Cunningham, and I am a high schooler in Boston. I have been weaving, knitting, and crocheting for over a decade, and also enjoy exploring the scientific methods behind these crafts. I wanted to experiment with dye-making techniques using more affordable and accessible materials, like onion skins!

Onions originated in Asia and the Middle East, but the exact period and geographic origin are uncertain. Turkish artisans in the mid-1400s started using onion skins to dye carpets and rugs. Additionally, many artisans still use these methods to create authentic rugs today. Natural Dyes were also used by early Navajo artisans, who are known for their woven rugs and blankets. Many started using natural dyes in the 1700s and, in Navajo weaver Mable Burnside-Myer’s Dye chart, she shows the use of onion skins in her work.

Due to their high level of tannins, onion skins do not require a mordant to create vibrant color and adhere to natural fibers, making them effective and adaptive dyestuffs. Additionally, by adjusting the potency of the dye bath, and adding iron, or copper, the color of the fibers can change dramatically, allowing a large range of colors to be created. While onion skins do not appear in the manuscript, the dyeing process is almost identical to that of cochineal and other dyes used at the time. Using onion skins, more people can experiment with dye-making without having to find rare and expensive ingredients.

Notes and pictures - raw data

- Template and notes used during dyeing processes for calculations and record keeping:

- Flickr Album with all photos

Summer 2022 First Dye Experiments

First round - 07/07/22 - prepping the onion skins and using alum as a mordant

- Based off the recipes I found, there was no consistent ratio between onion skins to amount of textile to water

- I used 7.5 grams of textile and the onion skins from 5 yellow onions (they were very hard to weigh; my scale was not sensitive enough to give me a number so I’m guessing it was 2 grams or less)

- This was a lot less onion skins than the websites I was looking at used, but it worked well. In the future I want to try different ratios and see how it affects the color, but you need a LOT of onions for that.

- Additionally, I want to try using red onions to see if/how that changes the color

- I ended up heating the onion and water for 1hr and 20 minutes, but again there was no magic number for how long to heat the onions so I think anything over an hour would work

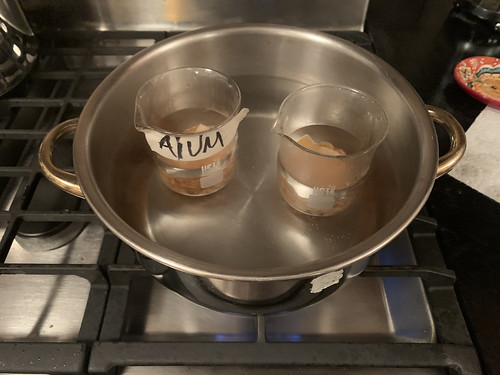

- I also prepared my mordant, alum, just using the information from the sandbox, I used the standard ratios and followed the general mordant and dye process

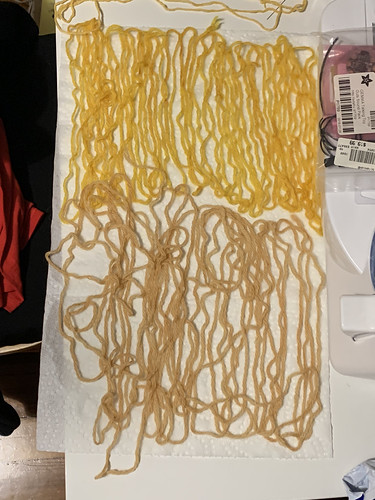

- I only used a mordant for half of my textiles, while the alum definitely gave the textiles (a wool sample and a cotton blend sample) a bunch brighter and vibrant orange/yellow color, the textiles without mordant picked up color well, leaving a pale brown/yellow

- In total I had about 150 mL of the onion skin dye bath, even with a small amount, it dyes the textiles well

- Overall this was a very successful attempt at dying, there are definitely things I want to keep exploring, but all things considered it worked very well. One thing that’s great about the onions is that there is a lot of forgiveness throughout the process. The vague and very different ratios and processes I was reading about were a little confusing at first, but I think ultimately show precision is not a necessary component for this process, which makes it a perfect starting point for people who want to try natural dyes

Second round - 07/12/22 - adding iron and copper

- Unfortunately, I did not have enough onions to make a new dye bath, so I created a mordant bath for the iron and copper and put the textiles I had already dyed in them

- I used the ratios from the DYE AND MORDANT RECIPES document for ratios

- I had two baths, iron and copper, but four different bundles - iron, iron + alum, copper, copper + alum

- Pretty straightforward, I just followed the standard mordant bath recipe as described above and put my textiles in

- In some of the websites, they were able to achieve lighter and more vibrant greens, so I want to try different ratios, especially with the iron sulfate to get a bigger range of green values.

- The copper sulfate made the textiles without alum and the textiles with alum basically the same color, I wonder if this is because they were in the same beaker or if copper had the same effect on the onion dye regardless of the alum

Fall 2022 Second Dye Experiments

-

Wanted to create a greener color, I liked the yarn that had been dyes with onions and iron last time. Additionally, because of the tannins in the onions, I did not notice a huge difference between using alum or not and so I decided not to put any of my samples in an alum bath.

-

I decided to start by experimenting with the level of iron included used to alter the dye and I wanted to see what happened when the iron and copper were both used on the same fiber

-

I started by extracting the color from the onion skins – simmering skins in a pot with water for 30 min – 1 hour

-

This round, I had a lot more onion skins and was able to create a much more potent dye bath, last time I used the onion skins from about 3-4 onions and this time I used the skin from 6-7 onions

-

After letting the skins simmer for 20 min, it was apparent that this dyebath was much darker than my last one. It was much more orange, almost red and opaquer than my last dyebath which was yellow and translucent

-

Additionally, instead of removing the onion skins, I just put in my wool fibers into the simmering pot and let it absorb the color for about 30 min

- I believe this also played a part in the darker colors I was getting

-

My wool was much more orange this time and much darker - I did not expect it to be so dramatically different

-

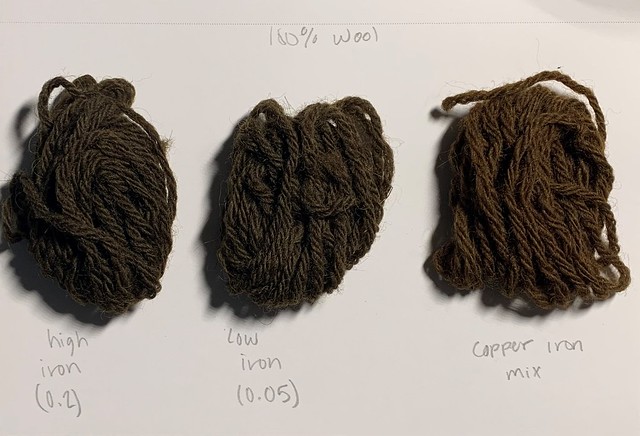

I put the three samples of wool in to their respective baths, (0.2g:50ml iron to water, 0.05g:50ml iron to water, 0.05g:0.05g:50ml iron to copper to water)

-

The two pure iron samples changed to a much darker brown color almost immediately upon entering their iron baths

-

All the samples ended up being pretty dark brown. The one with copper was warmer shade of brown whereas the purely iron samples were cooler tones. Also, the two iron samples are almost indistinguishable

Final thoughts

-

I think my goals were hindered by the initial onion skin dye bath, so I definitely want to do another round of dyeing with a less concentrated dyebath

-

Onion skins are hard to measure precisely and I want to find a way to standardize my methods – maybe counting how many onions used more carefully or getting a more sensitive scale

-

I also want to repeat this experiment with a less potent onion skin dyebath to get lighter colors

-

I am also curious to see how dark I can make wool with onion skins. The cool toned fibers were really interesting as onions skins dyes start out very warm toned