sandbox

The “Sandbox” space makes available a number of resources that utilize and explore the data underlying "Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640" created by the Making and Knowing Project at Columbia University.

Pictures Worth 1,000 Words: Figures and their Uses in Ms. Fr. 640

Sophie Macomber

Summer 2021

Have you ever tried following a new recipe that didn't have any pictures? Not even a picture of the end result? It's hard, right?! While pictures might seem to add clutter when you're just trying to figure out how much water to add to four cups of flour or exactly to what temperature the oven needs to be set, they can be meaningful tools for communicating other kinds of information, and their use in instruction manuals and notebooks dates back centuries (see also Leonardo Da Vinci's notebooks for a contemporaneous example of the use of figures), as can be seen in Ms. Fr. 640, a sixteenth-century collection of practical techniques.

|

|

|---|---|

| Folio 94r: Furbisher Sword guard. |

Folio 112r: For Tempering Sand Equipment for making sand molds, including bowls, spoon, brushes, clay bases and walls, a snake, and a lizard. |

Working with the Making and Knowing Project, I have begun to appreciate multiple methods of acquiring knowledge, particularly through words, practice, and pictures.

Texts

So much of our daily lives, and particularly modern academia, is deeply rooted in text. From textbooks to primary sources such as the BnF Ms. Fr. 640 to even this blog post, we most frequently read words in order to gain information. However, what about concepts that words may be insufficient to describe? Or when a word could take on a number of different interpretations?

When exploring texts on the making of products or commodities, this is frequently the case. Historical texts in particular rely on a wealth of common knowledge that is assumed to be known by the practitioner, which has since been lost to time; therefore, many of the instructions that we might expect to find within a recipe today are missing. For example, the recipe for making Bisket Bread in The Good Housewives Jewel, a 1587 culinary text by Thomas Dawson, contains no measurements of liquids used in the recipe, leaving us in our attempt at reconstructing the recipe to guess whether we had gotten it right.

|

|

|---|---|

| My interpretation of Bisket Bread | My Partner’s Interpretation of Bisket Bread |

See More: Historical Culinary Recreation: Bisket Bread Presentation

Reconstructions

This sort of practical knowledge, the insights gleaned from hands-on recreations of recipes, has been instrumental in our understanding of Ms. Fr. 640. As Pamela Smith explains in her essay "Making the Edition," the recipes contained in Ms. Fr. 640 need reconstructing "in order to begin to understand their implausible instructions, such as bread molding, and an alchemical process of producing a powder for gold by enclosing silkworms in a vessel."

Project Theme: Practical Knowledge from The Making and Knowing Project on Vimeo.

Project Theme: Practical Knowledge, dir. Lan Li, 2017. Pamela Smith discusses some of the insights gained in 2016–2017, when the Making and Knowing Project focused on practical knowledge, including vernacular natural history, practical perspective, optics, mechanics, and medicine. © Making and Knowing Project (CC BY-NC-SA).

While these reconstructions can be useful in order to understand these texts in a laboratory setting, this approach can be limited in a practical sense. When performing our own reconstructions of recipes within Ms. Fr. 640, we must often make assumptions about the true meaning of the author-practitioner. For example, in reconstructing the process of molding from bread, which used the soft inner part of the bread known as the "pith" as our mold, we had to make decisions on whether to remove the pith from the crust or to simply leave it in. I personally had greater success not removing the pith; however, it is unclear whether this decision would have been supported by the author-practitioner.

|

|

|---|---|

| Bread molding with pith remaining in crust and with pith removed from crust | Resulting cast wax objects |

For more information see: Field Notes: Bread Molding Reconstruction

Others, both historical and modern individuals, attempting to use these recipes may not necessarily have the wealth or resources to learn from multiple attempts and would only have one shot to get it right. Even if the practitioner replicating these recipes was a craftsman who would be making the recipes multiple times for sale, it could still be too much of a burden to livelihood to have too many practice attempts before making a saleable commodity.

Pictures

Images and figures offer a middle ground between the often insufficient text and the sometimes costly world of practice. Through figures, the author can provide crucial visual information to guide the practitioner in the right direction of making and give hints about the correct final product. These figures and images can be easier to understand and provide more information than a thick block of text.

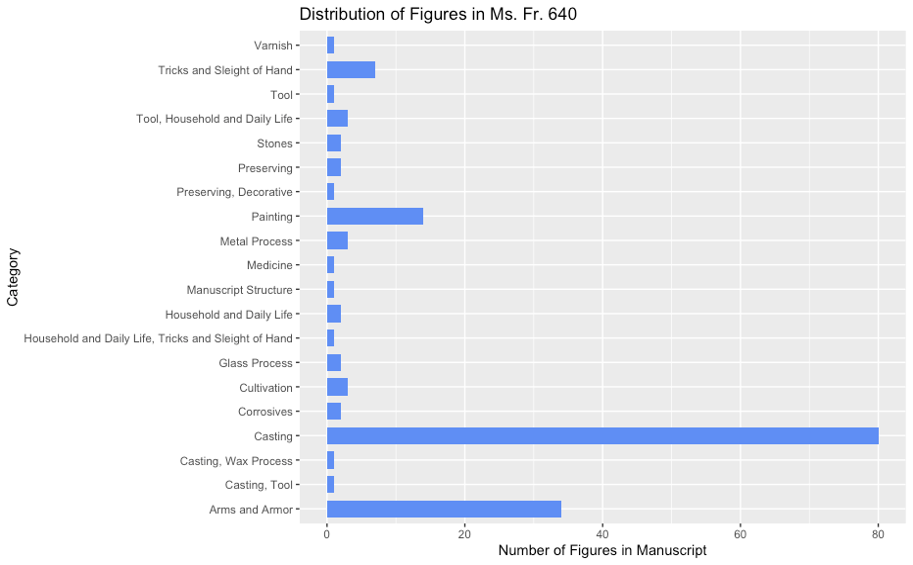

Within Ms. Fr. 640, the author-practitioner provides 162 hand-drawn figures to aid his reader (or perhaps himself?). Entries with these figures make up a minority of the 928 entries in the manuscript. Most of these figures illustrate aspects of processes described within the recipes. Half of these figures, 82 in total, are associated with a casting process. Perhaps this suggests that this category of entries is more complicated than the others, necessitating more figures in order for the future practitioners to replicate the recipes. Alternatively, it could be a sign that the author-practitioner is more familiar with the casting process and is thus more comfortable with providing further detail in figures.

|

|

|---|---|

| Folio 117r: A means of molding flowers and plants Plant with wax on its stem that will form a gate for casting. |

Folio 160r: Press for the large molds Press for large molds composed of two square sheets between four poles connected at the top by a screw. |

With 34 entries (not quite a quarter of the total), those relating to arms and armor have the second most figures. Almost half of these figures (15 in total) are related to the measurements or weights of cannon balls. This is followed by painting and then sleight of hand tricks.

|

|

|---|---|

| Folio 27r: Medium ball Circle that encloses its label representing the caliber of a medium cannon ball. |

Folio 33r: For relighting an extinguished candle between your hands without blowing Hands relighting a candle. |

See su21_macomber_figures.R for sourcecode of this chart.

Text and Figure

While breaking down the figures by category allows us to gain information about when the author-practitioner felt that it was necessary to utilize figures, we must turn to how the figures are integrated into the manuscript in order to determine how the author-practitioner worked the figures into the manuscript as he was writing.

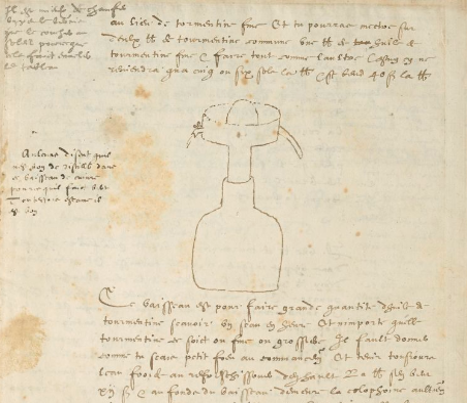

The figures within the manuscript vary in size. Most can be characterized as small (75 figures) or extra small (53 figures) rather than large (10 figures) or medium (24 figures). This suggests that the figures might be meant to enhance or supplement the text of the entries rather than being the main focus.

|

|

|---|---|

| Fol. 113r: Making the arrangement and disposition of the animal A dead snake arranged for lifecasting on clay slab, held in place with pins Extra Small Figure |

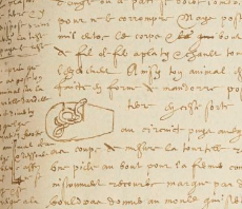

Fol. 3v: Thick varnish for planks Distillation vessel Medium Figure |

The figures in the manuscript also vary in where they are physically located on the page. While most of the figures (97 figures) are drawn in the margins of the page, 65 of the figures are drawn within the entry itself. This can potentially shed valuable light on how the author-practitioner values the images: images that are directly integrated into the text of the manuscript might be deemed more vital for someone attempting to replicate the recipe, while the figures in the margins might be helpful but not entirely necessary. It's possible that the character of entries with the figures integrated into the main body of text would be fundamentally altered without the figure.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Fol. 61r: Lights Double-walled iron funnel with labels ‘a,’ ‘b,’ and ‘c.’ Figure in Margins |

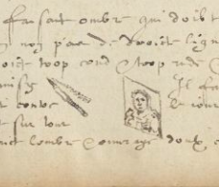

Folio 33v: For making blood or wine issue from someone’s forehead or from a wall Paintbrush and its shadow with portrait on panel. Figure Integrated in Text |

el with labels 'a,' 'b,' and 'c.'Figure in Margins |

Figures as Clues to the Manuscript's Composition

On the other hand, the integration of the figures within the manuscript can tell us a lot about the author-practitioner's writing process. In the figure in the entry on folio 16r', "Founding of Soft Iron," the text wraps around the body of the image, making it appear as if the author-practitioner had drawn the figure before writing the text, only to find that the entry was longer than he had initially planned for. This approach to composing the manuscript, with some of the images drawn before the writing, makes a lot of sense if you consider the labor that would have gone into writing each page by hand: it would be a huge waste of labor to write out an entire page just to make a mistake in a large, detailed figure and need to redo the entire page.

Similarly the relation between the figures and text and the author-practitioner's composition process becomes clear in the entry on folio 64v, "Apprenticeship of the Painter." The author-practitioner writes "One also presents him with these strokes & lines" and provides a figure that illustrates the said strokes and lines (folio 64v); however, between that text and the figure, the author-practitioner inserts additional text that explains the figure in further detail. From this, it appears that the author-practitioner wrote the quoted passage and drew the figure before adding further elaboration later, perhaps because he assumed the figure was not sufficiently explanatory. For a more detailed evaluation of the image and text on fol. 64v, take a look at Wenrui Zhao's essay on the Apprenticeship of the Painter.

|

|

|---|---|

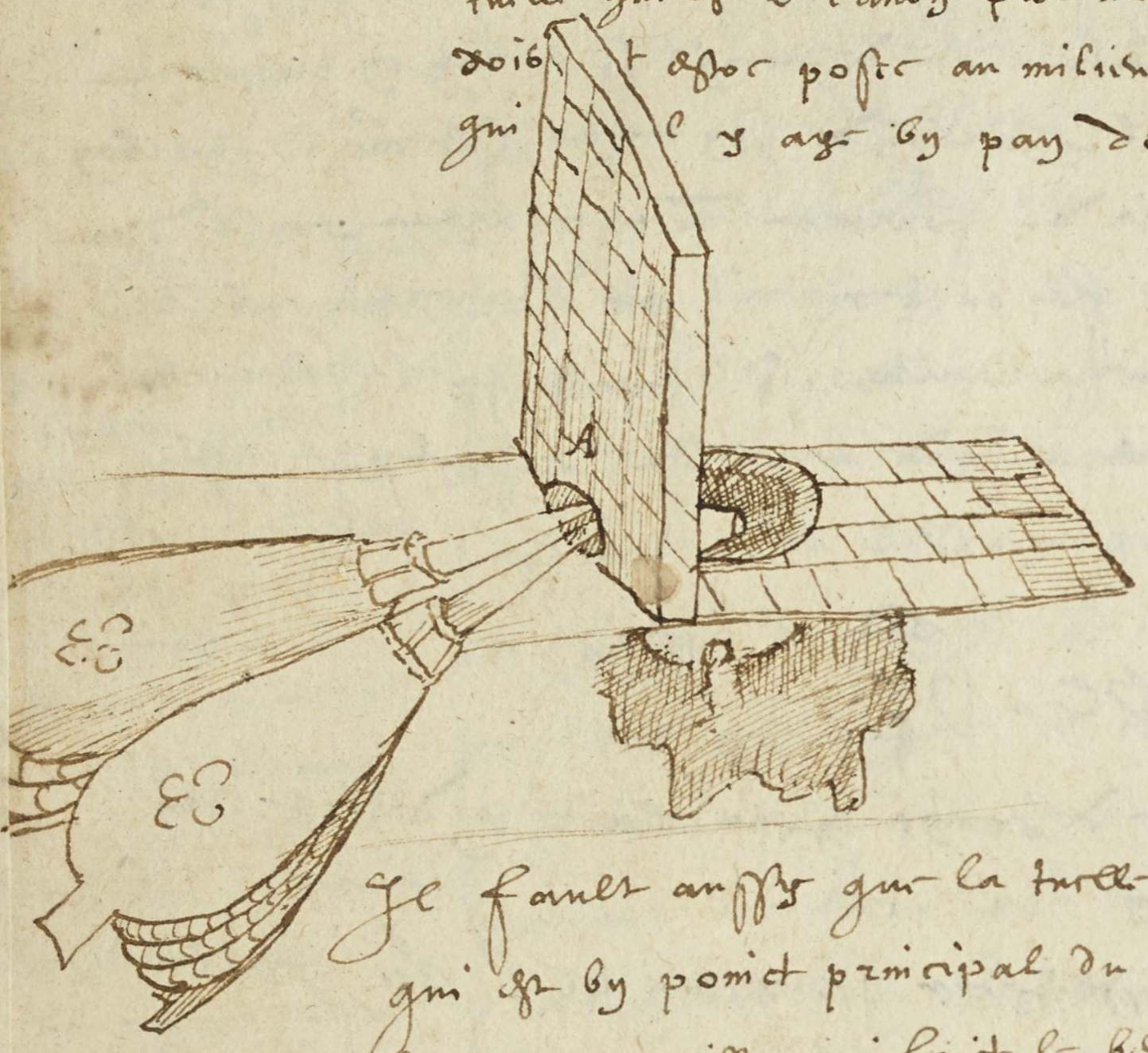

| Folio 16r: Founding of soft iron Furnace with blast pipe and bellows. |

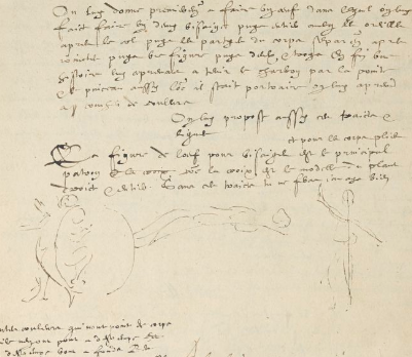

Fol. 64v: Apprenticeship of the painter Three forms for drawing figures with faint outlines of bodies. |

Using the Figures

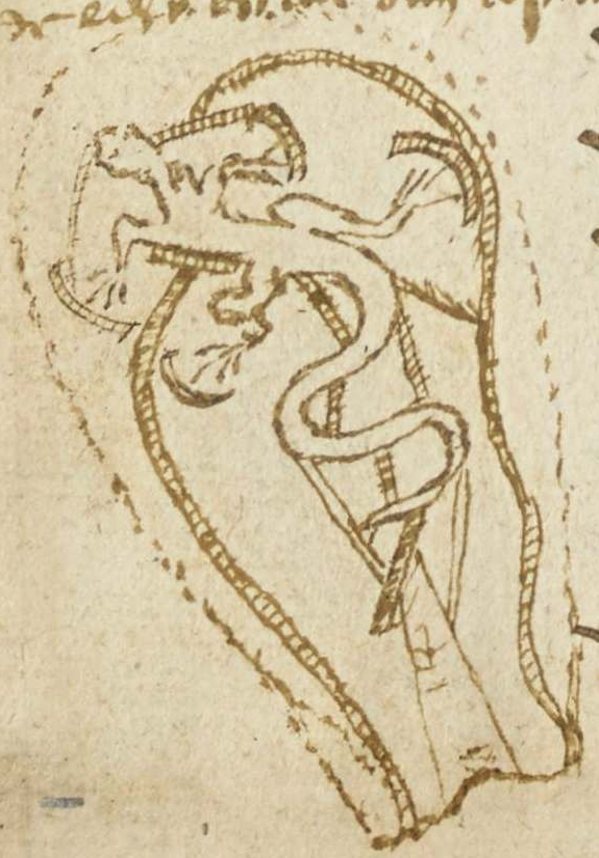

How useful are these figures anyway? While further work is needed to fully explore the use of these images, such as which figures serve as illustrations or which serve as diagrams, it is clear that these figures were made with a practical purpose in mind. For example, the figure in " A means to make the gate for small female lizards" (folio 124v), which is a recipe for lifecasting a lizard, makes little sense to a reader unfamiliar with the art of lifecasting; however, as Professor Smith found in her work in reconstructing this recipe, it would have been almost impossible to replicate the recipe without the image. Thus, the images do serve a practical purpose, particularly for those with some familiarity with the content of the recipe.

|

|---|

| Folio 124v: A means to make the gate for small female lizards Mold of a lizard with channels for casting. |

Conclusion

While today we rely on photographs or computer generated figures (such as the above bar graph) to convey information, the author-practitioner had to draw out each figure by hand, accurately enough to be of any use to a future reader. The figures are drawn with incredible skill, each clearly recognizable for what they are, some even including shading and dimensions. Moreover, they shed light on the author-practitioner: while the author-practitioner's artistic talents should not be a surprise considering that the nature of many of his entries, from painting to casting, are artistic in nature, the figures are an intimate window into the individual behind our anonymous author-practitioner. Tracing the lines of the figures, it is easy to imagine the focused artist doing the same with his quill. Despite the many recipes (and thus objects) which the author-practitioner must have produced, these figures are the only product, the only representation of artistic mastery we have from the author-practitioner himself.

Works Cited

Smith, Pamela H. "Making the Edition of Ms. Fr. 640." In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_329_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/zdaf-cv31