sandbox

The “Sandbox” space makes available a number of resources that utilize and explore the data underlying "Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640" created by the Making and Knowing Project at Columbia University.

Animal Rationality in Ms. Fr. 640

Victoria Nebolsin

Making and Knowing: Hands-On History

May 2022

Ms. Fr. 640 reveals a surprisingly symbolic treatment of some of the animals with which the author-practitioner engages. While overall the manuscript possesses a mostly practical, straightforward approach, several passages on animals display language that sings with metaphor. Snakes are explicitly compared to Satan (fol. 109v), rats are compared to the tyrant of Syracuse 152r), and pigs can understand Greek (13v). The attention that the author-practitioner allots to animals only amplifies the perplexing nature of these remarks. As Pamela Smith underscores:

Ms. Fr. 640 provides observations on the habits of animals used for casting, including instructions for catching, feeding, and killing them, along with extremely detailed firsthand experimentation in molding and casting them. The author-practitioner treats lifecasting in dense passages from fol. 106v right through to the end of the manuscript…1

Smith follows this description with the statement that “it is clear that lifecasting was a major preoccupation (perhaps the major preoccupation) of the author-practitioner.” In confronting the immense effort dedicated to living creatures, the symbolic details swell with larger implications. Understanding the symbolism necessitates identifying the underlying values that drive the author-practitioner’s craft.

Ms. Fr. 640 is not unusual in its emphasis on animals. Many artifacts of art and architecture from early modern Europe reveal efforts to imitate nature,2 and such efforts often focus on animals. One example appears in amulets used for pregnancies. In The Body of the Artisan, Smith uncovers the meticulous drawings of amphibians found in a goldsmith’s workshop. She writes that these images were most likely “used as models for amulets cast in metal” that “were ‘to be placed on the head of a 29-week pregnant woman.’”3 Frogs and amphibious creatures—animals equipped to shift between land and water—were frequently used for childbirth talismans. Smith elaborates:

These drawings of amulets give us insight into a web of connections: the verisimilitude of the apprentice’s drawings mattered because knowledge and efficacy resided in nature. Nature had to be imitated to bring into operation natural processes; processes that were bound up with the workings of the human body. In the artisan’s attempt to imitate nature, he strove to create effects by employing the powers that inhered in nature.4

The amulets suggest that the author-practitioner might also have had such a view of animals: that they are not simply brute beasts to be tamed, domesticated, and/or consumed; they have something that can protect, heal, or teach humans.

Ms. Fr. 640’s entries on lifecasting demonstrate a concerted effort to master and comprehend the “knowledge and efficacy” to be found in animals. In this essay, I will argue that the metaphorical interludes, rather than being oddities in Ms. Fr. 640, provide insight into the author-practitioner’s understanding of what this “knowledge and efficacy” might mean. Specifically, I will look at entries that suggest that animal knowledge contains a degree of rationality. By comparing the rat to a tyrant and claiming pigs can understand Greek, the handbook grants a degree of reason to these creatures. Furthermore, these comparisons reveal echoes of Plutarch, an ancient writer who argued against the Stoic denial of rationality to animals.5 I hope to explore Plutarch’s influence on Ms. Fr. 640. In doing so, I aim to show how the author-practitioner unchains reason from its link solely to the human realm. I will treat the manuscript’s metaphors not as idiosyncrasies, but as evidence of the author-practitioner’s belief in the reasoning powers of beasts. Specifically, I will look at the entries on the rat (152r), pig (13v), and snake (109v).

The Tyrant Rat and Vermin-Killing Manuals

In the entry on “Molding a rat” (152r), the entry states: “the hairs of its whiskers would be awkward to come out in the cast; you can therefore shave them with fire, like the tyrant of Syracuse, & afterward you can replace them with natural silvered ones”—the said tyrant being Dionysius I of Syracuse, who burned off his beard rather than trusting a barber who could potentially slit his throat. The tyrant metaphor composes only a small feature of this extensive, sharply technical entry, but the disparity makes it stand out all the more. Anthropomorphizing this vermin does not denote an eccentricity on the author-practitioner’s part; in fact, this is extremely common in early modern texts. “In the [early modern] vermin pamphlets and literature…greed is a defining quality of such animals, sometimes leading to comic tales in which they are caught because they can’t give up a choice morsel,” Karen Raber writes,6 and evidently, the comparison to a Greek tyrant, hungry for power, corresponds to such an attitude. But where do these ubiquitous views of avarice stem from?

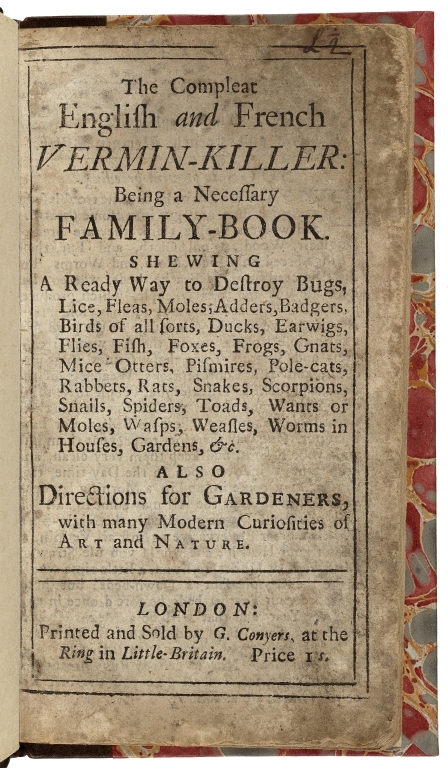

During the early modern era, vermin competed with humans for resources. These animals inhabit a unique position in that they were not eaten, nor cultivated for any practical or aesthetic purposes, yet still played a significant role in everyday life. Rather than hunting for their own food, vermin scurry into the household to poach human food. In fact, as Mary Fissell indicates, vermin were “defined legally in Elizabethan and Henrician statutes which authorized parishes to provide payment for the killing of vermin injurious to grain,”7 a sign of their ability to leave humans hungry. In response, vermin-killing manuals began to gain popularity in the rapidly expanding industry of early modern cheap-print books. These often noted that the pests died because “they ate greedily:” in A Necessary Family-Book, Both for the City & Country, in Two Parts (1688),8 the author describes how “they will greedily eat it, and it quickly will killeth them.” Fissell connects their continuous vilification to the need to allay anxieties about killing them. She cites James Serpell to highlight the dark undercurrent of this anthropomorphism, exposing how these highly negative terms served to justify the vermin’s extermination.9

The Compleat English and French Vermin-Killer, 1710, Folger 230–673q, https://shakespeareandbeyond.folger.edu/2020/01/21/rats-early-modern-life-shakespeare-plays-wild-things/.

In early modern texts, vermin were portrayed as “trickster figures, endowed with more than animal intelligence, engaged in eternal battle with humans over […] materials essential to human existence—meat, grain, fabrics, wood.”10 Capturing mice and rats, as a result, became a true struggle; rat catching meant that the individual would not only need to have knowledge of rats and their behavior, but also become skilled in using snares and poisons against these sly creatures. Humans would have to enact the knowledge of specific technologies as a way to stay one step ahead. Fissell notes that the inclusion of vermin-killing in a “book of secrets” was logical because outsmarting these pests implied knowing a few tricks. She writes:

The key that linked vermin-killing, magical tricks, and recipes for preserving pears was not domestic management. Rather each represents a manipulation of the natural world through cunning…legerdemain involved fooling the audience, vermin-killing required fooling the animals, and preserving fruit involved fooling the natural process of decay…“science” and “secrets” were wholly intermingled.11

This relates directly back to Ms. Fr. 640 as several of its entries span not only the molding of rats, but the preservation of perishables, as well as several tricks, including disguising a horse (54v). In some ways, the reference to the tyrant of Syracuse alludes to an evenly matched battle of wits occurring outside of the manuscript. Though there are no explicit vermin-killing entries, there are several references to catching animals (lizards and snakes [107r]; crayfish [160v]) for the purposes of lifecasting. We can speculate that the author-practitioner hunted his rat as well, and in portraying him as Dionysius, an animal rationality emerges: the rat is a worthy opponent, mobilizing his greed and cunning to conquer the cupboard’s treasures.

While the author-practitioner explicitly compares the rat to a dictator, the vermin-killing manuals are not as harsh. The Compleat English and French Vermin-Killer (1710), for example, names tyrannical traits, but does not go so far as to depict tyranny itself. The manual simply sticks to words such as “selfish” and “very destructive.” Similarly, The Vermin-Killer (1680), an earlier manual, fixates on avarice without any mention of bloodthirsty exploit. So, where does the author-practitioner’s impulse to reference Dionysus come from?

Vermin-killing manuals were not widely available until after Ms. Fr. 640’s publication, but the race to eradicate rats was well underway by the 1580s (its likely period of composition). Whether officially compiled into manuals or not, methods to outwit vermin were commonly exchanged orally. In France, the battle between trickster vermin and frustrated humans eventually grew to include the legal system. Bathélemy de Chasseneuz, one of the leading French jurists of the century, “owed his reputation to his work as counsel for a group of rats who had been put on trial before the court of Autun on the charge of having eaten up and destroyed the barley crop of that province.”12 The 1522 rat trial of Autun was well-known throughout France; it created enough fame for Chasseneuz to sit on the highest courts in Paris, Burgundy, and Provencal. “From that day onward, he enjoyed a meteoric career as a consulting lawyer,” writes Jan Bondeson.13 Defending the rats presented a particularly arduous task due to the overwhelming efforts employed against them. Chasseneuz realized this when he saw the “pompous clerics, dressed in their best habits, elaborate at length about the bad character and notorious guilt of the accused rodents before a vast crowd of peasants dressed in their Sunday finery, listening to their tirades with rapt attention.”14 His winning of the case, and commitment to finding obscure legal loopholes, earned him nationwide renown. Even so, the rats continued to be reviled as gluttonous felons.

The trial of Autun paints a telling picture of how rats were perceived in early modern France. Autun’s citizens were so exasperated by the vermin’s tyranny over their crop that they took the pests to court; there, ill repute was weaponized against them. It is this exasperation that would lead to the vermin-killing manuals. It is also these “crimes” that the author-practitioner would be aware of in compiling Ms. Fr. 640. The Dionysus metaphor then seems more appropriate, for in molding the rat, the author-practitioner is molding the outlaw that ravages the country’s harvests. But why Dionysus, specifically?

“Burning His Whiskers Like the Tyrant of Dionysus”: Plutarch’s Influence

The reference to Dionysus in “Molding a rat” evokes not only the aforementioned trial of Autun, but a potential influence by Plutarch as well. His text Parallel Lives records the reigns of both Dionysius I (the better known tyrant) and Dionysius II as a comprehensive study of both their political tenures and the subsequent consequences. In fact, Plutarch mentions Dionysus’s distrust of the barber twice—first, in a work from Moralia titled “On Talkativeness,” then in Parallel Lives. In “On Talkativeness,” Dionysus slays the barber that mocks his “unbreakable despotism” and who sneers, “fancy your saying [that Dionysus is unbreakable], when I have my razor at his throat every few days or so!”15 In Parallel Lives, the reference to Dionysus’s barber makes the parallel between Plutarch and Ms. Fr. 640 more evident. He writes: “for the elder Dionysus was so distrustful and suspicious towards every body [sic], and his fear led him to be so much on his guard, that he would not even have his hair cut with barbers’ scissors, but a hairdresser would come and singe his locks with a live coal.”16 Here the singeing of the locks mirrors the singeing of the rat’s whiskers.

If the manuscript did, in fact, adopt the rat image from Plutarch, it reveals a telling detail about how the author-practitioner might have approached animal life. Plutarch did not only write about tyrants. As stated earlier, he is also the ancient world’s most avid advocate for animal rationality. Stephen T. Newmayer highlights that Plutarch:

devoted three treatises of his Moralia to questions relating to the nature and moral status of animals. Plutarch touched upon the question of justice toward animals in De esu cranium (On the Eating of Flesh), a defense of vegetarianism … and in Bruta animalia ratione uti (Whether Beasts Are Rational), an amusing parody of Odyssey X cast in the form of a dialogue between Odysseus and the philosophic pig Gryllus (“Grunter”), one of Circe’s victims who declines the hero’s offer to convince the witch to reconvert him into human form and who advances the position that animals are morally superior to humans.17

The author-practitioner would certainly have been exposed to Plutarch, and, more likely, would have been reading him. In France, the first edition of Plutarch was published by Gilles de Gourmont on April 30, 1509. This was the inaugural event in a series of Plutarch publications that created a sweeping interest across France. In the introduction to Plutarch’s Lives, Alain Billault indicates:

From 1530 to 1540, 27 books by Plutarch were published in France, including 15 French translations, six Latin translations, three editions of the original text and three volumes which contained Greek text and facing Latin translation. Those figures confirm that Plutarch had indeed become a popular writer in sixteenth-century France.18

It was Jacques Amyot—a bishop, scholar, writer, and translator—who brought Plutarch to a French audience; he was Plutarch’s main translator during the Renaissance. In the Classical Weekly, James Hutton writes that: “Amyot’s Plutarch is the most important monument of French prose between Calvin’s Institutes (French version, 1541) and Montaigne’s Essais (1580).”19 He goes on to state that Amyot had already written the bulk of Montaigne’s Essais, as so much of Essais appears as “either a simple transcription or a paraphrase of Amyot’s Plutarch.” In Hutton’s view, the translator was not merely working on a “popular” text, but on a monumental contribution to French history. “If one is sometimes inclined to think that it has played a part in French history comparable to that of the Authorized Version of the Bible in English history…let it be noted that Amyot approached his task in something of the spirit of one translating a sacred text,” Hutton declares.20

Taken together, Billault and Hutton demonstrate just how important Plutarch was during the author-practitioner’s time. The ancient writer’s texts were immensely popular during Ms. Fr. 640’s writing and the Amyot translations became a defining point in French literary history. This makes the rat entry’s reference to Dionysus appear less anomalous. Steeped in a society attuned to Plutarch’s work, the author-practitioner likely pulled from Parallel Lives. Subsequently, it would not be a surprise if Ms. Fr. 640 pulled from Whether Beasts Are Rational as well.

Summoning the Swine

According to the Ms. Fr. 640, when swine and snakes hear their names called in Greek, the latter is sure to flee while the former will come to the caller (13v). The author-practitioner declares, “it is said that if one calls a snake in Greek, saying ΟΦΗ ΟΦΗ [meaning snake], it will flee. Likewise, if one calls a swine in Greek, ïon, it will come.” At first glance, this entry perplexes with its nonsensical commentary. What is this isolated, fantastical entry doing in a book on artisanal knowledge? However, the fact of Plutarch’s popularity in early modern France is a first clue. In Whether Beasts Are Rational, Plutarch features a Greek-speaking pig; and in the popular Renaissance text by Giovanni Battista Gelli, titled Circe, a Greek-speaking serpent slithers forward.

Whether Beasts Are Rational unfolds as a parody of Odyssey X, illustrating a dialogue between Odysseus and a philosophical pig who was once a human. Plutarch names the pig Gryllus (“Grunter”); he is a verbose victim of the spell Circe cast to condemn Odysseus’s men to swinehood. Gryllus staunchly believes in the superiority of pigs to men, and though Odysseus attempts to convince him otherwise, the grunter does not budge. He gestures to all the natural abilities found in animals, while underscoring the strained effort that composes human life. The pig proclaims:

Animal intelligence…allows no room for useless and pointless arts; and in the case of essential ones, we do not make one man with constant study cling to one department of knowledge and rivet him jealously to that; nor do we receive our arts as alien products or pay to be taught them. Our intelligence produces them on the spot unaided; as its own congenital and legitimate skills. I have heard that in Egypt, everyone is a physician; and in the case of beasts each one is not only his own specialist in medicine, but also in the providing of food, in warfare and hunting as well as in self-defence and music, in so far as any kind of animal has a natural gift for it.21

The passage above condenses Gryllus’s overall point: why transform into a clumsy, striving human when skill and knowledge come so naturally to animals? Food, hunting, medicine—Gryllus lists what he considers to be innate gifts. Humans, on the other hand, must pursue these practices with intention. Ms. Fr. 640 is itself an example of such misfortune.

Recall the amphibian amulets used for childbirth. Smith traces this imitative practice to the desire “to create effects by employing the powers that inhered in nature.” Plutarch adopts a similar point—that animals contain natural gifts man can only achieve through focused imitation. In Ms. Fr. 640, the author-practitioner’s painstaking efforts contain the same argument. Entries on lifecasting, natural antidotes, and raising silkworms to exploit them for alchemy demonstrate the manuscript’s overarching goal of coopting nature’s powers. The silkworm entry (53v), for example, specifies a way to trap the creatures, feed them, and harvest their transformative properties. As Sasha Grafit writes, “the…recipe involves hatching silkworm eggs in an enclosed flask where they are to feed on egg yolks and each other. When the sole surviving silkworm grows to resemble a serpent, it is burned and produces a toxic vapor—its ash is to be used to transmute metals into gold.”22 Silkworms contain the natural gift of transmutation; they transform from egg to worm to cocoon to moth. The author-practitioner, on the other hand, must artificially manipulate the worms to harness their transmutative potential.

If Gryllus and the author-practitioner are in agreement, then Ms. Fr. 640’s Greek-speaking pig appears less outlandish. Gryllus would have been a known figure in early modern France, especially for those pondering animal life. Additionally, the ability to summon swine would be a sought-after skill at the time. Unruly pigs were a common danger in early modern cities. Keith Thomas emphasizes, “in the towns of the early modern period, animals were everywhere…for centuries, wandering pigs were a notorious hazard of urban life.”23 Tamed swine had a habit of running off as well. Ralph Josselin recorded in his diary on July 5th, 1650:

I was troubled with my hogs breaking away on the lords day morning, and having looked for him and not finding him. I observed still a vexacon and trouble in all thes things and thinking gods providence might bring him backe to mee, I was just then told that he was driven home from of the greene.24

Even farmers did not have full dominion over their pigs. Together, the hazard of wandering pigs and the popularity of Plutarch unveil the potential logic behind Ms. Fr. 640’s puzzling entry.

Scaring the Snakes

In “Whether Beasts Are Rational,” Gryllus the Pig states, “I have heard in Egypt that everyone is a physician; and in the case of beasts each one is…his own specialist in medicine.”25 In Circe, Giovanni Battista Gelli portrays one such physician, except he is Greek, not Egyptian. He is also not human, but a snake.

Gelli’s Circe adopts Whether Beasts Are Rational, expanding it into a series of dialogues with eleven different animals who were formerly humans. Published in 1549, the text had “great vogue” in France and was even put into dramatic form.26 According to George Boas, La Fontaine imitated Gelli’s story in his famous fable Les Compagnons d’Ulyse.27 By the end of the century, Circe also benefited from numerous reprints.28 All of these factors point to a strong likelihood that the author-practitioner would have been familiar with the work.

Gelli’s animals are arranged according to an “interesting renaissance conception of the scale of animal being, since it starts with the oyster, and the mole and runs through the snake, the hare, the roebuck, the doe, the lion, the horse, the dog, the calf, and finally, the elephant.”29 In their dialogues, all prefer to remain a beast, save for the elephant. The animals largely base their arguments for superior virtues, knowledge, and perfections on “particular physical relationships to the world and its challenges. The snake, for instance, who was once a physician, details the miseries of human suffering, while celebrating the fact that animals never fall prey to excessive appetites or other vices.”30 That is to say that each animal formulates his or her position based on its knowledge of the material world.

The snake is a particularly fascinating figure, particularly for comparing Gelli and Ms. Fr. 640. Firstly, the Greek viper in Circe mirrors the Greek-speaking serpent from the manuscript. Odysseus asks the viper, “art thou the celebrated Doctor of Lesbos?” to which the snake replies affirmatively.31 The famed physician provides a trope that may have been circulated during Circe’s popularity, influencing the hearsay underlying Ms. Fr. 640’s entry. Secondly, and more interestingly, questions posed by the snake echo a human vulnerability which drives some of the manuscript’s practices. Boas writes:

As a physician, [the snake] was acquainted intimately with the human organism and complains of its general weakness…His main criticism is that although as a science [medicine] is true, dealing as it does with only the eternal and the universal, as an art it is purely empirical and we know next to nothing of the human body. That we are dependent upon it for health shows how unfortunate we are; the beasts have no need of it, for nature has given them controlled appetites and lusts, has taught them the remedies which they may need from time to time…32

Indeed, in Circe, the snake specifies that medical practice is based on experience, and that, in this respect, it is “very deceitful and uncertain.” He labels several physicians he knew as “cheats.”33 The viper then goes on to list every part of the human body, emphasizing a plethora of ailments corresponding to each one.34 “Nature is more indulgent to us than to you,” he hisses, “since he has taught every Species of us, and every individual belonging to that species, without any experience of Time or Mony, without any Study or Labour, without any Teaching or Instruction from others, to find out proper remedies for those ills.”35

Gelli’s snake creates a sense of irony when thinking about Ms. Fr. 640 as the manuscript is itself a product of study and labor with the goal of producing natural remedies. Specifically, the viper’s comments summon the image from the entry on molding the very same animal. In “Flower in the mouth of the snake” (122r), Ms. Fr. 640 specifies that “if you want to put in the mouth of the snake some flower or some branch of a plant which contains the antidote against its bite, take a little branch, as best arranged as you can find, & pose its stem into its mouth.” Arranging the snake with an antidote underscores the human vulnerability Gelli’s snake critiques. Positioning the two together may indicate the author-practitioner’s mastery over nature—man can capture snakes and concoct antidotes for their venom, too. However, the detail equally highlights a defenselessness. Humans do not possess natural protection against snakes. They do not have long fangs, sharp claws, or piercing beaks. Instead, they must pore over manuscripts to study methods of defense.

Serpents have a menacing role in Ms. Fr. 640. In the entry on “Molding a snake” (109v), the author-practitioner describes the animal’s behavior, writing that “they do not bite with a direct attack but with sinuous turns & from the side, as do Satan & his disciples.” Comparing snakes to Satan and his disciples illustrates a conniving cleverness in these animals. Like the tyrannical rats, vipers do not commit violence in a straightforward manner. They lie in wait and silently whip their supple bodies towards their target. On fol. 13v, calling the snake to make it flee may be quotidian hearsay, yet it emphasizes the fear of these predators; they are a true peril for humans. The specification of calling its name in Greek, though strange, conjures Gelli’s infamous physician. The snake sneers:

we [beasts] lie under no necessity of buying one another’s labour, of stealing degrees, of corrupting Nurses, of wheedling Apothecaries, or trying any dangerous Experiments upon ourselves and our friends; and what is infinitely worse, of paying an ignorant Rascal that bleeds us dry in the Pocket-vein, and sends us to our graves before our time, as you Poor Wretches are forced to do.36

Relying on Ms. Fr. 640’s trick—yelling Greek at a snake to make it flee—may be a dangerous experiment indeed.

Conclusion

These entries: “Molding a rat” (152r); “Snakes” (13v and 109v); and “Flower in the mouth of the snake” (41v) all contain elements that evoke images from Plutarch and Gelli, two authors who strongly advocated for animal rationality. Dionysus, Gryllus, and the snake-physician all seem to have influenced the manuscript, whether directly or through the surrounding culture. Knowing the popularity of these two authors during the sixteenth century, we can speculate that the author-practitioner could have been familiar with their work. It is also telling that Ms. Fr. 640 shares a central question with the texts: namely, can humans truly be masters of nature? In other words, does imitation by the human hand suggest supremacy or does it suggest the need to compensate for our vulnerabilities? Or both?

Through the manuscript’s treatment of animals, we can see that the author-practitioner did perhaps afford a degree of reason to animals, such as in the case of the snakes. If taken seriously, this signals that the hierarchy of humans and animals may not be so clear cut. Ms. Fr. 640’s puzzling details—Greek-speaking pigs, dictator vermin—puzzle the reader at first glance, but upon closer inspection, provide insight into sixteenth-century views of the relationships between human and beast.

Works Cited

Billault, Alain. “Plutarch’s Lives.” In The Classical Heritage in France. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2002.

Boas, George. The Happy Beast in French Thought of the Seventeenth Century. Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press, 1933.

Bondeson, Jan. “Animals on Trial.” In The Feejee Mermaid and Other Essays in Natural and Unnatural History. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014.

Fissell, Mary. “Imagining Vermin in Early Modern England.” History Workshop Journal, no. 47 (1999): 1–29. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4289600.

Gelli, Giovanni Battista. The Circe of Giovanni Battista Gelli of the Academy of Florence. Translated by Thomas Brown Gelli. London: J.N. Publishers, 1710.

Grafit, Sasha. “Silkworms and the Work of Algiers.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_059_sp_17.

Hutton, James. “The Classics in Sixteenth Century France.” The Classical Weekly 43, no. 9 (1950): 131–139. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4342690.

Josselin, Ralph. The Diary of Ralph Josselin, 1616–1683. London: The British Academy, 1976.

Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano, editors. Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org.

Meijer, Eva. When Animals Speak: Toward an Interspecies Democracy. New York: New York University Press, 2019.

Newmyer, Stephen T. “Just Beasts? Plutarch and Modern Science On the Sense of Fair Play in Animals.” The Classical Outlook 74, no. 3 (1997): 85–88.http://www.jstor.org/stable/43937959.

Plutarch. “On Talkativeness.” In Moralia. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. London: Loeb Classical Library, 1939. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/plutarch/moralia/de_garrulitate*.html.

Plutarch. The Parallel Lives. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. London: Loeb Classical Library, 1918.https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Dion*.html.

Plutarch. “Whether Beasts are Rational.” In Moralia. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. London: Loeb Classical Library: 1957. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/Gryllus*.html.

Raber, Karen. Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

Smith, Pamela. The Body of the Artisan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Smith, Pamela H.. “Lifecasting in Ms. Fr. 640.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_511_ad_20.

Thomas, Keith. Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England 1500–1800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 95.

-

Pamela H. Smith, “Lifecasting in Ms. Fr. 640,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020), https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_511_ad_20. ↩

-

Smith, “Lifecasting in Ms. Fr. 640,” https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_511_ad_20. ↩

-

Pamela Smith, The Body of the Artisan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 121. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Stephen T. Newmyer, “Just Beasts? Plutarch and Modern Science On the Sense of Fair Play in Animals,” The Classical Outlook 74, no. 3 (1997): 85–88, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43937959. ↩

-

Karen Raber, Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 121. ↩

-

Mary Fissell, “Imagining Vermin in Early Modern England,” History Workshop Journal, 47 (1999): 3. ↩

-

As cited in ibid., 5. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Raber, Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture, 119. ↩

-

Fissell, “Imagining Vermin in Early Modern England,” 14–15. ↩

-

Eva Meijer, When Animals Speak: Towards an Interspecies View of Democracy (New York: New York University Press, 2019), https://doi-org.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/10.18574/nyu/9781479859351.001.0001. ↩

-

Jan Bondeson, “Animals on Trial,” In The Feejee Mermaid and Other Essays in Natural and Unnatural History (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014), 132. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Plutarch, “On Talkativeness,” In Moralia (London: Loeb Classical Library, 1939), translated by Frank Cole Babbitt, https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/plutarch/moralia/de_garrulitate*.html. ↩

-

Plutarch, The Parallel Lives, translated by Frank Cole Babbitt (London: Loeb Classical Library, 1918), https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Dion*.html. ↩

-

Newmyer, “Just Beasts?” 85, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43937959. ↩

-

Alain Billault, “Plutarch’s Lives,” in The Classical Heritage in France (Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2002), 220. ↩

-

James Hutton,“The Classics in Sixteenth Century France,” The Classical Weekly 43, no. 9 (1950): 137. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4342690. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Plutarch, “Whether Beasts are Rational,” in Moralia, translated by Frank Cole Babbitt (London: Loeb Classical Library: 1957), https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/Gryllus\*.html. ↩

-

Sasha Grafit, “Silkworms and the Work of Algiers,” https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_059_sp_17. ↩

-

Keith Thomas, Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England 1500–1800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 95. ↩

-

Ralph Josselin, The Diary of Ralph Josselin, 1616–1683 (London: The British Academy, 1976), 209. ↩

-

Plutarch, “Whether Beasts are Rational,” https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/Gryllus*.html. ↩

-

George Boas gathers this from fragments cited by Saint-Marc Girardin in La Fontaine et les Fabulistes of Fuselier’s Les Animaux Raisonables. George Boas, The Happy Beast in French Thought of the Seventeenth Century (Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press, 1933), 35. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Raber, Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture, 10. ↩

-

Boas, The Happy Beast, 28. ↩

-

Raber, Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture, 3. ↩

-

Giovanni Battista Gelli, The Circe of Giovanni Battista Gelli of the Academy of Florence (London: J.N. Publishers, 1710), 42. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015023171559. ↩

-

Boas, The Happy Beast, 30. ↩

-

Gelli, The Circe, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015023171559, 79. ↩

-

Ibid., 52–56. ↩

-

Ibid., 79. ↩

-

Ibid., 57. ↩