sandbox

The “Sandbox” space makes available a number of resources that utilize and explore the data underlying "Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640" created by the Making and Knowing Project at Columbia University.

Regimens, Recipes, and Remedies: Understanding the “Cosmetic” in Early Modern Europe

Danli Lin and Anusha Sundar

Fall 2021, Making and Knowing in Early Modern Europe: Hands-On History

Introduction

A Google search of the word “cosmetic” yields many meanings, including anything related to beautification, correcting defects, decorating, and clearing one’s complexion. We are also immediately reminded of beauty models, or the scores of beauty products that line the aisles of supermarkets. There is also the endless barrage of advertisements featuring glistening hair, glowing skin, and miraculously spot-free skin! Yet, there is a longer history to the world of cosmetics that is not limited to the idea of beauty, just as scholars have pointed to how notions of beauty are historically contingent on regions, communities, gender, and social strata. This essay discusses how ideas about cosmetics were closely aligned to medicinal and therapeutic uses in early modern Europe. This will help us understand the multiplicity of meanings that these historical understandings and quotidian uses produced.

Manuscript recipe books in early modern Europe—ranging from books of secrets to craft treatises and how-to manuals—were extremely diverse. They often testified to the social networks that undergirded practices of recipe exchanges, patronage, and community interactions. In fact, Mary Fissell, a historian of medicine, has argued that this might be one of the critical explanations for the “wide array of recipes” that can be found in a single manuscript collection.1 With the advent of the printing world, recipe books became a market of their own, based on the success of certain well-known individuals or even compiled by printers and published for a dedicated audience. Often, printed compilations of cosmetic and household manuals carried a dizzying array of recipes with instructions ranging from the medicinal and therapeutic to the healing and culinary.

Beauty recipes were collected as part of these household manuals or compiled together in dedicated beauty manuscripts, and were dedicated to women running households. Yet, it is when they are found in hybrid texts such as Ms. Fr. 640 that they allude to wider knowledge networks and to vernacular frames of understanding the relationship between nature and the human body. Montserrat Cabré argues that it is important to investigate “the presence of beauty recipes and the earlier traditions they belong to” in order to understand the social and epistemological milieu that these recipes were a product of.2 Rather than approach cosmetic recipes as given facts, or trace their emergence, we must pause to reflect on their presence at different moments and in differing forms.

This essay situates the “cosmetic” within the world of the Hippocratic humoral theory, which informed notions about the body, wellness, and diet (among various other aspects) in early modern Europe. This is explored by examining recipes for two beautification regimens: ones that sought to maintain/correct one’s complexion and recipes directed towards whitening one’s teeth.

Complexion

Let us first examine two recipes from the sixteenth-century French manuscript Ms. Fr. 640. The manuscript contains a relatively small selection of forty recipes that can be characterized as dealing with cures for illnesses, diseases, and hazardous environs. It is noteworthy that two of these forty recipes attempt to alter, correct, and preserve the complexion of the human face. An entry on fol. 20v, titled “For whitening the face,” reads as follows:

Pestle puffball in cistern water, & no other, & wash with this whitened water. This is considered quite singular. And I believe that making it from wheat starch & to use it would be even better.

Another recipe on fol. 77r, titled “Against redness of the face,” appears to be similarly concerned with protecting the countenance of the human face:

Make a small lead cap & wear it overnight. Excellent secret. Try a lead mask.

At first glance, both these recipes seem to speak to daily cosmetic needs, but a closer look makes us wonder if they spoke to other therapeutic or medicinal concerns as well. In early modern Europe, cosmetic and therapeutic recipes often intersected with each other in ways that make it difficult for readers today to definitively slot them into distinct categories. While “For whitening the face” seems like a general regimen, “Against redness of the face” reads as a prescriptive cure for a person afflicted by a skin irritation.

A closer look at the ingredients might offer us a window into their shared medical/therapeutic uses. Famously, puffballs have been documented for their styptic function and were widely used in North America by indigenous peoples.3 In Europe as well, puffballs have been known for their ability to help cauterize wounds and internal hemorrhages.4 Lead compounds, on the other hand, had some of the most diverse uses, most of which would be shocking to today’s readers. From being used as a sweetener in wine by the Romans to being employed as a glaze in pottery, lead compounds—such as lead carbonate, lead oxide, and lead acetate—served many culinary, artistic, and aesthetic functions. Lead was also used by the aristocracy to rectify their complexion (think of Queen Victoria’s use of Venetian Ceruse, a white, powdery makeup composed of lead carbonate). The use of lead compounds as beauty enhancers was always tied closely to notions of luxury, religion, and health. Ancient Egyptians applied lead-based eye makeup with the understanding that it offered protections to the eyes and the skin around it.5 In medieval and early modern Europe, iatrochemistry practitioners such as Paracelsus advocated for preparing medicines using ingredients known to be toxic, such as mercury, lead, and arsenic. Interestingly, new research confirms some of this historical reasoning: limited use of and exposure to lead compounds does in fact promote an immunological response and can help treat eye and skin related illnesses.6

What does the blurring between toxicity and health tell us about how early modern Europeans perceived health and well-being? Historian Xiaomeng Liu has argued that recipe books from this period reflect “quotidian” ideas of the range of bodily suffering and human efforts to overcome, prevent, and better them.7 These quotidian ideas were dominantly governed by the humoral theory. Mary Lindemann tells us that in the humoral theory, “health rested in the balance of four humors—black bile, yellow (or red bile), blood and phlegm.”8 Essentially, each of the humors corresponded to qualities and temperaments of humans and cures that could potentially heal them. This was combined with a belief that the environment could affect and cause a disequilibrium in the humors. These notions extended to understandings of “complexion” as well, which, in the early modern world, carried connotations of the humoral balance or imbalance in a person. Complexion, therefore, evoked an image of the individual’s internal well-being as reflected in the external features such as the flesh and skin. It was only relatively recently that complexion began to refer restrictively to skin tones, much as it is used today.

The way the human face and body should be represented in art—as per instructions in craft manuals and treatises—also offers an important perspective into contemporary ideas about the body and human efforts to achieve bodily well-being. Cennino Cennini’s fourteenth-century Italian manuscript provides panel painters with information about the art of makeup, speaking to the overlap between the representation of nature and the human body, and elements of counterfeit and make-believe that went into achieving this semblance.9 Similar materials (such as egg yolk, resin, and lead white) were used to paint panels and to mix pigments to stain the human face. In her study of Ms. Fr. 640, Cleo Nisse points to the author-practitioner’s differential treatment for painting shadows of men and women.10 Women were considered to be cooler and wetter than men and thus phlegmatic and pale in complexion. Accordingly, artists were directed to paint a women’s body and face with white lead, vermillion, and Parisian red as opposed to using yellow ocher to depict men’s faces. Makeup containing lead white (lead carbonate) was especially used as part of face masks and powder upon which tints and stains were applied. In medieval and early modern Europe, women aspired for whitened faces, demonstrating how the prevailing aesthetic preoccupation was informed by the humoral theory.11 Not only does this underscore the medical conventions that undergirded representations of human flesh and skin, but also explains how the exterior was to reflect the internal balance of the humors. Seen in this light, recipes and regimens to “correct” one’s complexion speak to the ways in which the “cosmetic” was entangled with notions of medicinal/therapeutic understandings. In the next section, these entanglements are further considered by looking at recipes for tooth-whitening.

Teeth-whitening

The author-practitioner of Ms. Fr. 640 has recorded several approaches to teeth-whitening.

On fol. 47r, “For teeth” reads:

Sal ammoniac 1 ℥, rock salt 1 ℥, alum half an ℥. Make water with the retort, and as soon as you touch the tooth, the tartar & blackness will go away. It is true that it has a bad odor, but you can mix it with rose honey & a little cinnamon or clove oil.

“For the teeth, oil of sulfur” on fol. 46r advises:

Some people whiten them with confections of aquafortis; however, one says that this corrupts them afterward & causes a blackness on them. One says that oil of sulfur is excellent, but one needs to mix it in this way: take as much clove oil as can be held in a walnut shell, and as much rose honey, & seven or eight drops of oil of sulfur, & mix it well all together. And after having cleaned the teeth with a small burin, touch them lightly with a little cotton dipped in the aforesaid oils and leave it there for a little while, then spit or rinse your mouth with tepid water, and reiterate two or three times. Oil of sulfur penetrates & is corrosive, but the clove oil & the rose honey correct it. Therefore use it with discretion.

At the outset, both these recipes seem to speak overwhelmingly to cosmetic concerns. Although tooth decay was not as highly prevalent due to lower sugar content in the diet of early modern Europe, the presence of multiple recipes for teeth whitening speaks to anxieties about the appearance and well-being of teeth.12 Liu argues that even in cases where cosmetic use seems to dominate the purpose of the regimen, a closer look at the ingredients will help us approach this in a holistic sense.13 Clove oil, for example, was—and still continues to be—commonly prescribed to lessen and soothe toothaches. In one of the two recipes from Ms. Fr. 640, clove oil is mentioned alongside a range of ingredients used to treat teeth more broadly. Moreover, the two recipes to whiten teeth on folios 46r and 47r are placed together with cures to treat vertigo, diarrhea, dysentery, and cold gouts.

Recipes for teeth-whitening were common in other contemporaneous manuscripts and were central to beauty regimens, but they also testify to something more. In the mid-sixteenth century manuscript Cosmetic or, The Beautifying Part of Physick compiled by Mr. Nicholas Culpeper and acknowledged to having been “extracted” from the works of Johannes Jacob Wecker, a Swiss physician, we come across a range of recipes for “waters that whiten the teeth:”14

Take of salt Arabick, salt Gem, each half a pound, sugar’d Allom three ounces, powder and distil them, and rub the teeth with a scarlet cloth dipt in the water.

In another recipe, he accounts a “precious” method (the use of the word precious may possibly refer to an exhaustive list of ingredients, their relative availability, and cost):

Take of the first water of honey distilled, which is white, one pint, white Salt one ounce, Allom half a pound, salt Niter one ounce, water of the leaves of the Mastick tree one pint, Mastick, White-wine-vineger, each two ounces, distil them all in Bal: Mar: then rub the teeth with a Mastick stick dipt in it.

Wecker lists seven such recipes under “waters that whiten teeth” and proceeds with a list of recipes to “strengthen,” “fasten,” and “cleanse” the teeth and gum. For example, “A Water to strengthen the Teeth:”

Take three Nutmegs, two roots of Ginger, a little Mastick, Pellitory of Spain, sweet Marjoram, Hyssop, Mint, Rosemary, Sage, Salt, each half an ounce, put them all into sweet wine, and let them boil till a third part be consumed, then strein it well, and use it hot.

Prudently choosing distinct ingredients that could come together to fix the imbalance caused in the humors was the central preoccupation behind the knowledge systems of early modern Europe. In his study of tooth-drawers of seventeenth century Italy, David Gentilcore demonstrates how the practitioners’ services included offering a wide range of remedial substances alongside tooth extraction. The ingredients they used had less to do with the teeth per se and more to do with a practical knowledge informed by how “oils for cold humors” could protect the teeth and gum (which by virtue of being close to another, could be treated similarly).15 In Alessio Piemontese’s Secreti, a sixteenth-century manuscript penned in early modern Italy, we encounter several examples of recipes that combine efforts to “cleane the teeth,” “make them fast and white,” and conserve the gums.16 In one telling example of how the humoral theory was enacted, the author of Secreti directs the reader to follow three important lessons to ensure the teeth are white and uncorrupted: to wash one’s mouth after eating one’s meals, to not sleep with one’s mouth closed and to “purge well the breaste and throte, spitting out all that is gathered together that nighte.”17 According to the author, following these lessons is also particularly good for the well-being of the stomach and the head, an allusion to how the seemingly separate body parts were seen to be interconnected by humors. As in the Wecker manuscript and Ms. Fr. 640, therapeutic/medicinal recipes were positioned in a seamless continuity with more cosmetically-inclined recipes, speaking to how these methods were probably read as complementary factors to ensure a holistic well-being of the users.

This essay is an exercise in situating the rather unwieldy category of the “cosmetic” within the then prevailing knowledge system that was informed by the humoral theory. Notions about physical appearance and outward countenance were intimately tied to the internal state of the body. In such a scenario, the outward appearance was both a reflection of and a window into the well-being of the body. It was both the sign and the diagnosis of illness and health.

How some of the material ingredients in contemporary recipes compare with those found in Ms. Fr. 640

Early modern European manuscripts and contemporary practice/recipes represent the knowledge of these two time periods. When comparing and contrasting the ingredients mentioned in recipes from these two periods, we can get a better sense of how people perceive the material world and human body differently in the past and present. For instance, how do people whiten teeth in these two periods and what kind of ingredients do they use? Do people in the past and present use similar or totally different ingredients to make health/cosmetics products? The tables below show ingredients that appear frequently in recipes of Ms. Fr. 640 for enhancing one’s health and appearance. By comparing them, we may be able to get a sense of how people understand their bodies, materials, and the notion of cosmetics. Thus, let’s compare ingredients that early modern European people used with the ingredients that we often use in our present daily life to see what has changed.

Table 1: Whitening the teeth

| Recipe Source | Ingredients | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Ms. Fr. 640 recipes | Fol. 46r, “For the teeth, oil of sulfur:” oil of sulfur, clove oil, rose honey |

clove oil |

| Contemporary remedy | Toothpaste with hydrogen peroxide |  |

Table 2: Against redness of the face

| Recipe Source | Ingredients | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Ms. Fr. 640 recipes | Fol. 77r, “Against redness of the face:” lead (likely a lead compound) |

(Venetian ceruse - lead carbonate) Makeup pot with molded tablets of white lead found in a tomb from the fifth c. BC; at the Kerameikos Archaeological Museum.1 |

| Contemporary remedy | Soothing products such as creams and lotions containing ingredients such as niacinamide, sulfur, allantoin, caffeine, licorice root, chamomile, aloe, and cucumber |  Aloderma Soothing & Repairing Cream, https://aloderma.com/ Aloderma Soothing & Repairing Cream, https://aloderma.com/ |

Strangeremains, “Beauty to Die for: How Vanity Killed an 18th Century Celebutante,” Strange Remains, January 31, 2017, https://strangeremains.com/2017/01/31/beauty-to-die-for-how-vanity-killed-an-18th-century-celebutante/.↩︎

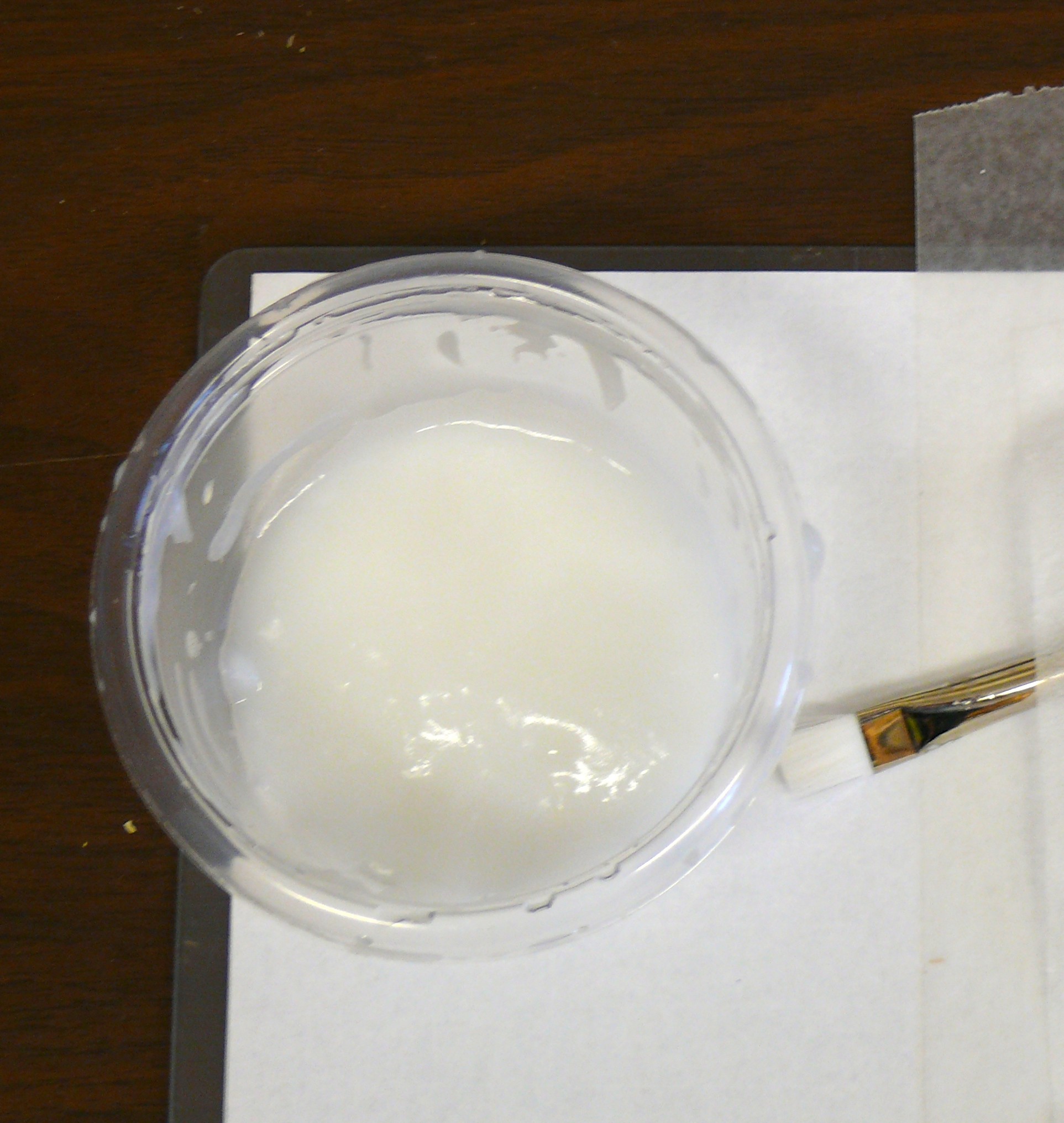

Table 3: Whitening the face

| Recipe Source | Ingredients | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Ms. Fr. 640 recipes | Fol. 20v, “For whitening the face:” Puffball and water, or wheat starch and water |

Wheat starch and water |

| Contemporary remedy | Niacinamide, Vitamin C (usually contained in skin care products to brighten skin tone) |

Niacinamide serum |

Table 4: Getting rid of the redness of eyes or bruising

| Recipe Source | Ingredients | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Ms. Fr. 640 recipes | Fol. 11v, “For getting rid of the redness of eyes or bruising:” sliced raw mutton flesh (applied to the skin/eyes) |  |

| Contemporary remedy | Ice (leave an ice pack in place for 10-20 min), or cool compresses over closed eyes |  |

Table 5: Against burns

| Recipe Source | Ingredients | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Ms. Fr. 640 recipes | Fol. 20v, “Against burn:” onion and verjuice, or black soap |

Raw natural black soap |

| Contemporary remedy | For minor burns: petroleum jelly or aloe vera |

Petroleum jelly |

Table 6: Against wounds

| Recipe Source | Ingredients | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Ms. Fr. 640 recipes | Fol. 55r, “Against wounds:” sap, pestled semperviva plant |

Semperviva herb |

| Contemporary remedy | Antibiotic ointment or petroleum jelly |

Antibiotic ointment |

Summary of the Recipes

Although recipes from each period (sixteenth and twenty-first centuries) are limited to varying degrees by the technology of the times, we can still compare them in general terms. From the six examples presented in the above tables, we can find a pattern that people in early modern Europe tended to use ingredients based on their experience, which includes knowledge from observation and experiment. For instance, herbs and the essential oil of herbs included on fol. 55r show the experimental basis. The author-practitioner mentions that before using the sap and semperviva for wounds, one should test the remedy by cutting a chicken or dog. The recipes for whitening and reducing the redness of the face use ingredients that can make people see the results directly based on people’s observations. For example, the use of lead powder can immediately cover the redness, although people didn’t necessarily know that it harmed the human body at the same time.

Today, lab-based experimentation and the extensive experience of trying and testing various ingredients has been formalized, and the process of making and knowing has been organized in this system. People tend to pay more attention to the useful components in ingredients instead of the ingredients themselves. For instance, we can see that products with aloe vera and petroleum jelly keep appearing in remedies for several skin issues since they all have a skin-soothing effect. For whitening teeth, toothpastes with hydrogen peroxide are recommended because of its bleaching properties. From the comparison of historical recipes to modern remedies, we can see that the use of ingredients is shifting from themselves to the active ingredients in them.

Bibliography

Bol, Marjolijn. “Medieval Makeup ‘Artists’. Painting Wood and Skin.” The Recipes Project, February 18, 2014. https://recipes.hypotheses.org/3344.

Cabré, Montserrat. “Keeping Beauty Secrets in Early Modern Iberia.” In Secrets and Knowledge in Medicine and Science, 1500-1800, edited by Elaine Leong and Alisha Rankin. Burlington: Ashgate, 2016, 179–202.

Fissell, Mary E. “Introduction: Women, Health, and Healing in Early Modern Europe.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 82, no. 1 (2008): 1–17.

Gentilcore, David. Essay. In Medical Charlatanism in Early Modern Italy, 190–91. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2006.

Lindemann, Mary. Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Liu, Xiaomeng, “Acid as Dental Cleanser and Tooth-Whitening Practices.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_058_sp_17.

Liu, Xiaomeng. “Collecting Cures in an Artisanal Manuscript: Practical Therapeutics and Disease in Ms. Fr. 640.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_057_sp_17. DOI:

Nisse, Cleo. “Shadows Beneath the Skin: How to Paint Faces in Distemper.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_042_sp_16.

Piemontese, Alexis [pseud.]. The secretes of the reverende Maister Alexis of Piemount: containing excellent remedies agaynste divers diseases, woundes, and other accidents, with the manner to make distillations, parfumes, confitures, dyings, colors, fusions, and meltings. Trans. William Warde. London, 1568.

Poitevin, Kimberly. “Inventing Whiteness: Cosmetics, Race, and Women in Early Modern England.” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 11, no. 1 (2011): 59–89.

Stamets, Paul and Heather Zwickey. “Medicinal Mushrooms: Ancient Remedies Meet Modern Science.” Integrative medicine (Encinitas, Calif.) vol. 13, no. 1 (2014): 46–7. PMC4684114.

Strangeremains. “Beauty to Die for: How Vanity Killed an 18th Century Celebutante.” Strange Remains, January 31, 2017. https://strangeremains.com/2017/01/31/beauty-to-die-for-how-vanity-killed-an-18th-century-celebutante/.

Tapsoba, Issa, Stéphane Arbault, Philippe Walter, and Christian Amatore. “Finding out Egyptian Gods’ Secret Using Analytical Chemistry: Biomedical Properties of Egyptian Black Makeup Revealed by Amperometry at Single Cells.” Analytical Chemistry 82, no. 2 (2009): 457–60.

Wecker, Johann Jacob, and Nicholas Culpeper. Arts Master-Piece, or, the Beautifying Part of Physick. London: Printed for Nath. Brook at the Angel in Cornhil, 1660. http://ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/cosmeticks-beautifying-part-physick-which-all/docview/2240935566/se-2?accountid=10226.

-

Mary E. Fissell, “Introduction: Women, Health, and Healing in Early Modern Europe,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 82, no. 1 (2008): 9. ↩

-

Montserrat Cabré, “Keeping Beauty Secrets in Early Modern Iberia,” in Secrets and Knowledge in Medicine and Science, 1500-1800, ed. Elaine Leong and Alisha Rankin (Burlington: Ashgate, 2016): 179–202. ↩

-

Paul Stamets and Heather Zwickey, “Medicinal Mushrooms: Ancient Remedies Meet Modern Science,” Integrative medicine (Encinitas, Calif.) vol. 13, no. 1 (2014): 46–7. PMC4684114. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Issa Tapsoba et al., “Finding out Egyptian Gods’ Secret Using Analytical Chemistry: Biomedical Properties of Egyptian Black Makeup Revealed by Amperometry at Single Cells,” Analytical Chemistry 82, no. 2 (2009): pp. 457–460, ↩

-

Xiaomeng Liu, “Collecting Cures in an Artisanal Manuscript: Practical Therapeutics and Disease in Ms. Fr. 640,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, ed. Making and Knowing Project, et al. (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020), https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_057_sp_17. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Mary Lindemann, Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013). ↩

-

Marjolijn Bol, “Medieval Makeup ‘Artists’. Painting Wood and Skin,” The Recipes Project, February 18, 2014, https://recipes.hypotheses.org/3344. ↩

-

Cleo Nisse, “Shadows Beneath the Skin: How to Paint Faces in Distemper,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, ed. Making and Knowing Project, et al. (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020), https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_042_sp_16. ↩

-

Kimberly Poitevin, “Inventing Whiteness: Cosmetics, Race, and Women in Early Modern England,” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 11, no. 1 (2011): pp. 59-89, ↩

-

Mary Lindemann, Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013). ↩

-

Xiaomeng Liu, “Acid as Dental Cleanser and Tooth-Whitening Practices,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, ed. Making and Knowing Project, et al. (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020), https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_058_sp_17. ↩

-

Johann Jacob Wecker and Nicholas Culpeper, Arts Master-Piece, or, the Beautifying Part of Physick (London: Printed for Nath. Brook at the Angel in Cornhil, 1660). http://ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/cosmeticks-beautifying-part-physick-which-all/docview/2240935566/se-2?accountid=10226. ↩

-

David Gentilcore, in Medical Charlatanism in Early Modern Italy (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2006), pp. 190-191. ↩

-

Alexis Piemontese, The secretes of the reverende Maister Alexis of Piemount: containing excellent remedies agaynste divers diseases, woundes, and other accidents, with the manner to make distillations, parfumes, confitures, dyings, colors, fusions, and meltings, trans. William Warde (London, 1568). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩