Was Ms. Fr. 640 Intentionally Disorganized?

Mackenzie Fox

Summer 2021

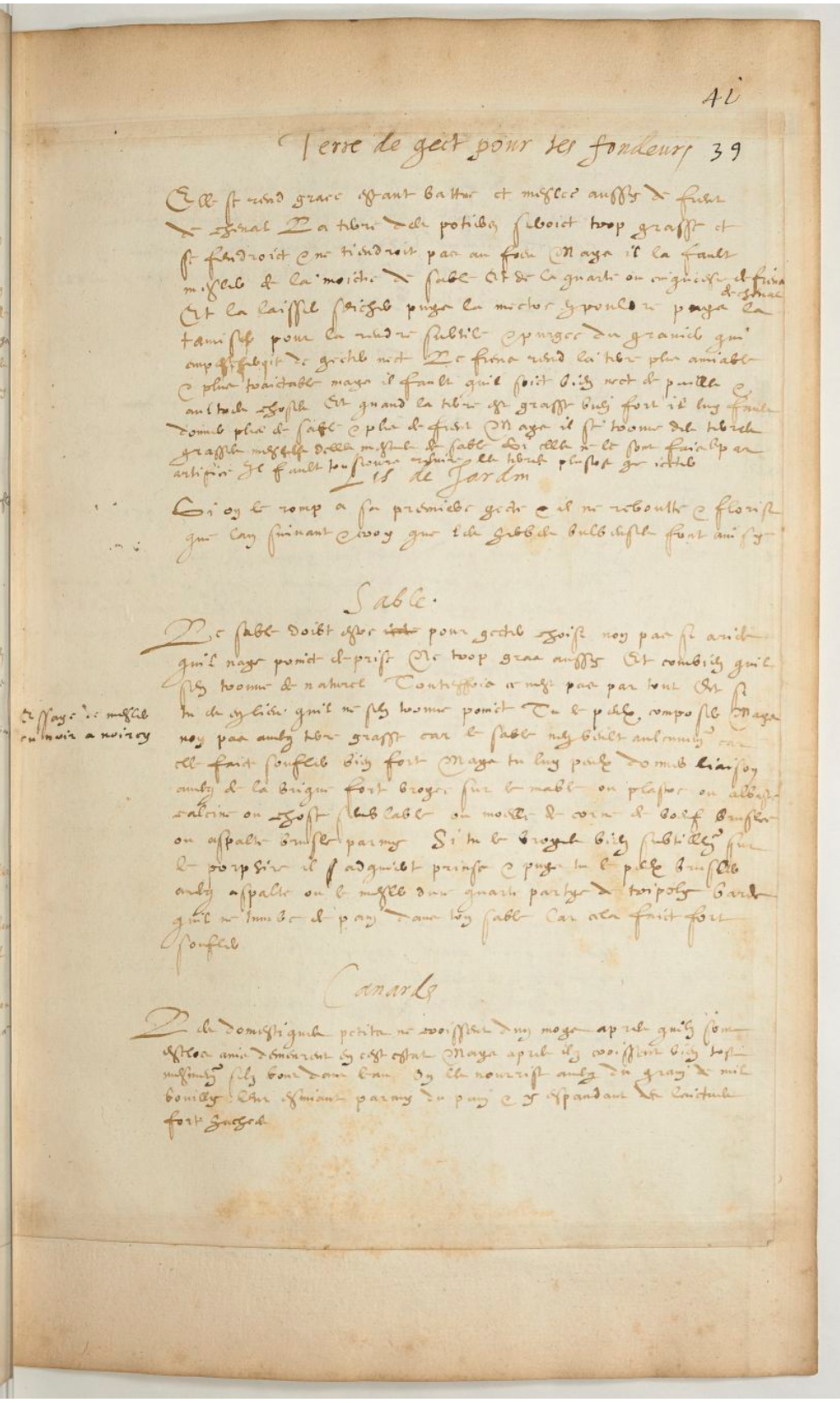

When browsing through the wide range of how-to instructions in BnF Ms. Fr. 640, it is often frustratingly unclear why the author-practitioner chose to address such disparate topics in a single text, or why he chose to arrange them in such an apparently random way. Why, for instance, does he, in the space of a single page, give advice on how to prepare earth for making molds to cast metal, record an observation about the ways in which garden lilies grow and flower, offer yet further advice on the appropriate type of earth for use in casting, and, finally, discuss the rate at which ducklings grow and how one should feed them?1 (See image below for the page in question, fol. 41r) Does he perceive a relationship between the topics covered in these entries? Was he simply jotting down information as it occurred to him as he went about his life? Was Ms. Fr. 640 a work in progress that the author intended to rearrange at a later date before publication or wider circulation?

As these questions suggest, it is not clear how much importance — let alone what sort of importance — should be ascribed to the coverage and organization of the text in its received state given how little we know about the author-practitioner and his motivations in writing the text. In the blog post that follows, I explore one intriguing possibility, i.e., that the text was intentionally miscellaneous or disorganized. I first briefly introduce the genre of the “miscellany,” that is, of miscellaneous texts with little obvious structure or organization, and highlight the remarkably similar ways in which miscellanies in Renaissance Europe and Song Dynasty China (970-1279 CE) seem to have emerged historically and to have troubled scholars in the present looking to understand their significance for intellectual history. Having established a baseline, I ask whether it is useful to think of Ms. Fr. 640 as a miscellany, and whether the author-practitioner’s choice of form might, indirectly, at least, suggest something about his motivations in compiling it.

_______

As their name implies, “miscellanies” are, broadly defined, texts that contain a wide range of information and yet lack clear thematic structure or categorization of that information. In the context of the European Renaissance, the historian Neil Kenny has suggested that miscellanies were, as a category, defined in contrast to a more prestigious and prevalent genre: the encyclopedia.2 Renaissance encyclopedias were not the alphabetical reference texts that we are familiar with today (let alone the searchable, digital counterparts of such texts like Wikipedia); instead, they were intended, as their name reflects, to contain an entire “circle of learning,” or a complete assemblage of all the knowledge an educated man ought to know. It was, then, their lack of concern with (and even enthusiasm for not) presenting information as part of a coherent, curated program that made miscellanies so utterly unlike encyclopedias.

For Kenny, this difference in how encyclopedias and miscellanies arrange information reflects an intellectual rather than merely generic division: between the encyclopedic approach to knowledge (or encyclopedism) and the miscellaneous approach. Encyclopedism, as Kenny presents it, valued system. In arranging knowledge to form a complete circle of learning, those of the encyclopedic bent sought not merely to provide an educational program (though they did seek this), but also to arrange knowledge in a way that, as they saw it, reflected “the inner structure both of the world and the human mind.”3 By contrast, the miscellaneous approach forswore such efforts at systematic, metaphysically significant organization. Rather than attempt to collect universal and essential truths, miscellanies often focus on the particular and impermanent. For these reasons, Kenny often presents miscellanies as offering a direct challenge to the encyclopedic model; they seem to invert or reject the model’s most essential values of system and philosophical coherence. Indeed, many miscellanies explicitly challenge the encyclopedic approach, though, as Olivia Branscum notes in her essay for the edition of Ms. Fr. 640, Secrets of Craft and Nature, “others simply offer alternatives to that way of seeing the world.”4

In light of this context, it seems reasonable to ask: should we think of Ms. Fr. 640 as a miscellany? By arranging his material as haphazardly as he does, was the author-practitioner offering an alternative to the encyclopedic approach to knowledge, or even taking a stance on the side of the miscellaneous against it? As Vera Keller suggests in her essay for the edition, there are reasons to believe both that the author-practitioner was self-consciously participating in a pan-European discourse,5 and that he viewed his text and its approach to knowledge as distinct from and likely to be dismissed by the mainstream.6 Keller also notes that the author-practitioner refers to a well-known educational text, the Tablet of Cebes, that, though it had been lost, had become a symbol of hierarchical division between different sorts of knowledge, apparently dismissively; he writes: “Tablet of Cebes, idle, but the workshop represents all things active,”7 suggesting that he rejected its placement of philosophy atop all other forms of knowledge, including the practical sort with which he was chiefly concerned.

Fig. 2. Tabula Cebetis (The Tabula of Cebes or The Journey of Human Life), Netherlandish, 1573. Oil on panel, 119.5 x 177 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-2372.Permalink: http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.4688 (CC0 1.0).

Vera Keller describes the image as follows: “This Christianized version of the Tablet of Cebes shows the temple of divine wisdom towering over the landscape. In this version, the mechanical arts (artes mechanicae), symbolized by figures spinning, chopping wood, and working at a forge, are located surprisingly deep within the structure of learning, within the second wall to the right. They have not yet begun the ascent to more abstract knowledge, however.”8

To reject the hierarchy of knowledge represented by the Tablet of Cebes is not the same, however, as objecting to the systematization of knowledge characteristic of encyclopedism. It does not seem to be the case that the author-practitioner harbors the same sort of resentment towards the encyclopedists or to organization; if he does, at least, he does not express it explicitly. Moreover, despite the often haphazard arrangement of the entries in the text, there are sections where a surprising degree of thematic unity can be spotted. From fol. 21r through 28r, there is an unbroken succession of entries to do with cannons and gunpowder weapons. From fol. 33r through 36r, there is a similarly consistent stretch of entries that have to do with tricks.9 Even in the example cited at the beginning of this post, two entries on the same subject — the best sort of earth to use for casting — appear quite near each other, though quite different sorts of information are interspersed between them. We see, then, evidence that the author-practitioner does not seem to have been self-consciously avoiding thematic arrangement, even if he was not consistent in pursuing it either. In short, there is nothing about this sort of organization that suggests a belief that all of the varieties of knowledge covered should be understood through the lens of a particular overarching theory or that they are intended to form part of a circle of learning. On the other hand, there is also nothing to suggest deliberate opposition to attempts to do so. As Olivia Branscum notes, the text thus seems to be irreducible to either an encyclopedic or miscellaneous text, as it contains elements characteristic of both genres without obviously committing itself to one or the other.10 How should we make sense of Ms. Fr. 640 in light of this? As a means of working towards an answer, it may be useful to briefly turn to a remarkably similar puzzle faced by historians of Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE) China working to make sense of miscellany-like texts that emerged quite outside of the European Renaissance context.

_______

In some ways not unlike European Renaissance miscellanies, the miscellany-like genre usually referred to as biji 筆記 (brush notes) rose to new prominence during an era (the 11th and 12th centuries) dominated by intellectual systems.11 During the 11th century in particular, a number of scholars, lamenting the sorry state of learning and of the world in the present, proposed new, systematic philosophies through which they proposed to reform this state of affairs. In Song China, however, intellectuals inclined towards systems and systematization generally did not compile comprehensive, encyclopedia-like texts. Instead, they most often expounded their ideas through commentaries on the five classics, which were said to contain the wisdom passed down by the sages of antiquity, since lost, that had provided the basis for life and government during the idealized distant past they had governed; they are: The Book of Changes 易經, The Book of Odes 詩經, The Book of Documents 書經, The Book of Rites 禮記, and The Spring and Autumn Annals 春秋.

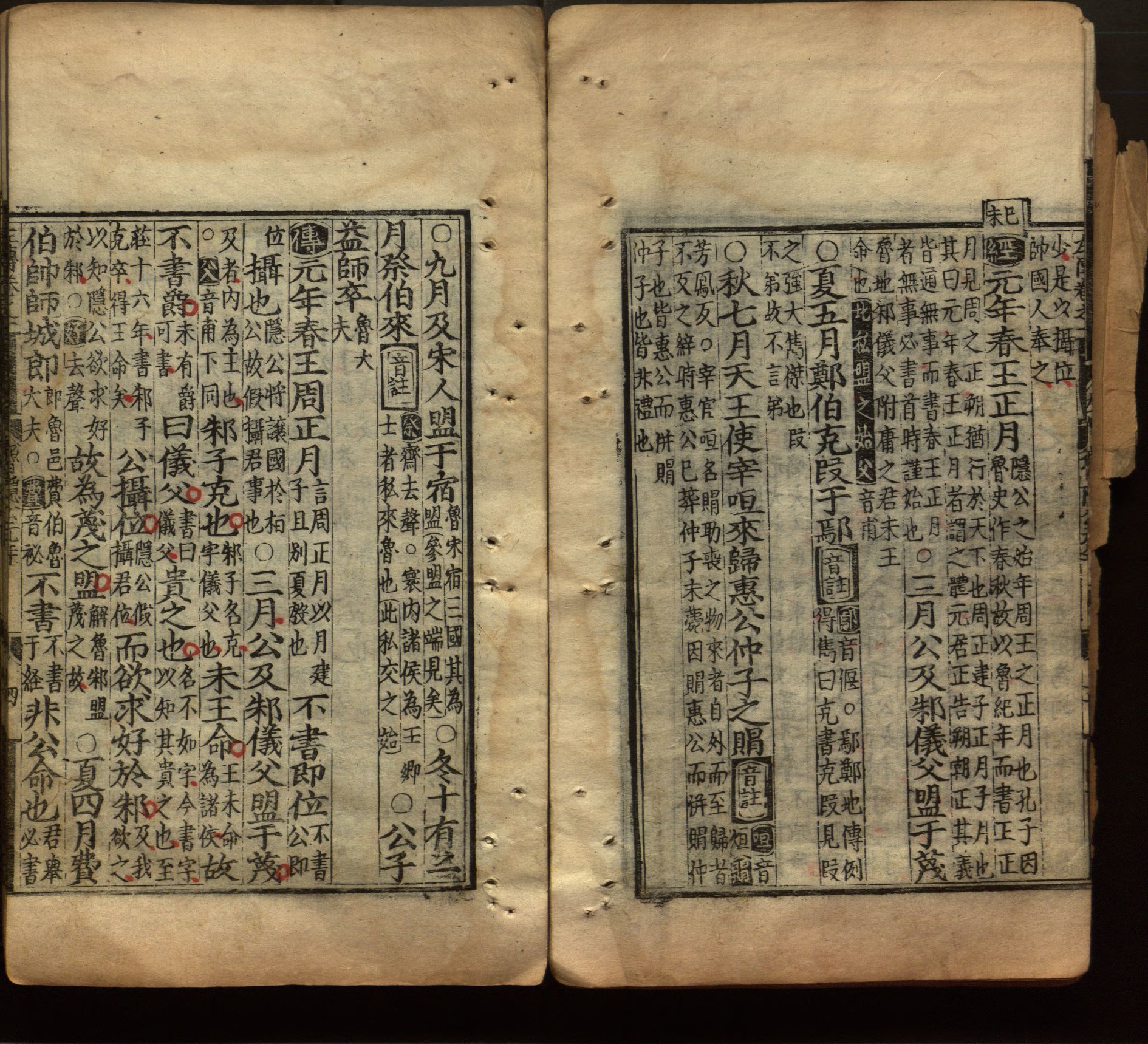

Fig. 3. Du, Yu, 222-284, Yaosou Lin, Quan Yang, and Chinese Rare Book Collection. Chun qiu Zuo zhuan: san shi juan. Chengdu fu zhi fu: yang quan, ming jiajing, between 1523 and 1566, 1523. Image. https://www.loc.gov/item/00510379/.

Above are two pages from a 16th century printed edition of the semi-canonical Zuo Commentary 左傳 on The Spring and Autumn Annals. The Annals recorded the history of the state of Lu 魯 from 722 to 481 BCE in extremely sparse detail, but, as it was traditionally thought to have been compiled by Confucius, was believed to contain his judgments on politics and morality, if in very oblique ways. The ambiguity left by the extremely sparse text spawned an enormous commentarial tradition that sought to explain its significance, within which the Zuo commentary, first written around the 4th century BCE, came to be revered nearly as much as the Annals itself, as it described the events recorded in the Annals in far more detail than the original text.12

(Reminder: Traditional Chinese texts are read from top to bottom and then from right to left) On the right page and in the first three lines of the left page, all of the large-format characters are taken from the original text of the Annals. (This beginning of this section is marked with the character 經 [classic] against a black background) The large-format characters seen on remainder of the left page (i.e., everything after the character 傳 [tradition; here short for zuozhuan 左傳 or the Zuo Commentary] against a black background) are from the Zuo commentary. The small, half-width characters on each page are commentary written by a later writer, Lin Yaosou 林堯叟 (ND). The format of the text is quite typical; the original text of the classic (including the Zuo Commentary in this case, given its semi-canonical status) appears in larger, darker characters, while the commentary appears in half-sized characters after it. This is an extreme example given that there are essentially two layers of commentary present, but it gives a sense of how much more verbose commentaries could be than the classical texts they were interpreting.

Biji, in contrast to the prestigious classical commentary, were rarely the sites where authors chose to discuss their views on such lofty matters as learning and government; instead, they were an informal context in which intellectuals could record and circulate their thoughts on nearly any topic that might strike their fancy. To give a sense of the diverse material that biji might contain, some of the most common sorts of entries include anecdotes about historical figures, observations about regional customs, philological investigations and, perhaps most interestingly for our purposes, observations about the material world and various technologies and craft methods. As an example of the style and tone typical of entry belonging to this category, consider the following excerpt taken from an 11th-century biji called Mingdao Zazhi 明道雜誌 (Miscellaneous Notes Illuminating the Way). In it the author, Zhang Lei 張耒 (1054-1114), a prominent official and literatus, offers a lengthy consideration of whether the pufferfish or hetun 河豚 (commonly known today by its Japanese reading fugu) is, in fact, lethally poisonous, drawing on hearsay from a range of sources including his friends, courtesans, and “local people,”:

The pufferfish is an extraordinary delicacy among seafoods, yet tradition has it they are poisonous and capable of killing a man and that, if one ingests the poison and subsequently feels swelling in one’s stomach, it can be resolved so long as one quickly eats some filth; otherwise, one will certainly die. Now I have served as prefect of Danyang as well as Xuancheng and have seen the people of those places eating it. They boil it without any particular method, and using only three items [when doing so] — artemisia (louhao), reed sprouts (disun) and cabbage (songcai) — is said to be most appropriate. They use cabbage to remove its fat and nothing more than that, yet none have died. Some say that the locals are accustomed to it and thus it does not harm them, but this is absolutely not the case…..

河豚魚,水族之奇味也。而世傳以為有毒,能殺人,中毒則覺脹,亟取不潔食乃可解,不爾必死。餘時守丹陽及宣城,見土人戶食之。其烹煑亦無法,但用簍蒿、荻筍、菘菜三物,云最相宜。用菘以滲其膏耳,而未嘗見死者。或云土人習之,故不傷,是大不然。13

Zhang continues his discussion for several hundred more characters, concluding without reaching a verdict on the central issue, though seeming to suspect that the hetun is not poisonous after all in light of the evidence considered; this tentative tone, leaving open the possibility that further information could alter a preliminary judgment is also quite common. Biji often stop short of definitive judgments.

Fig. 4. A pufferfish in a tank at a restaurant in Nagoya, Japan. Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Fugu in Tank.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Fugu_in_Tank.jpg&oldid=485810013 (accessed June 21, 2021).

Zhang’s dependence on what he had personally seen or heard (wenjian 聞見) in evaluating the claim that hetun are poisonous is typical of Song biji, which generally place a high value on knowledge derived from personal or indirect experience; unlike Ms. Fr. 640, however, biji writers like Zhang rarely seem to have personally conducted hands-on experiments or trials in verifying claims, perhaps because it would have been thought uncouth for a scholar to do so. Zhang’s choice of subject is also typical of the biji genre in that, despite its lack of clear relevance to broader philosophical or intellectual discourse, it is obviously intriguing to Zhang; biji, insofar as their contents are steered by any clear principle, most often seem to simply follow the whims and interests of their authors. That Zhang’s whims and interests are extremely diverse, then, also seems to be typical of biji authors. The Mingdao Zazhi includes entries that are simply jokes and puns, that address philological problems, discussions of physiognomy, tales of the supernatural, musings on where the best wine in the country is to be found, etc.

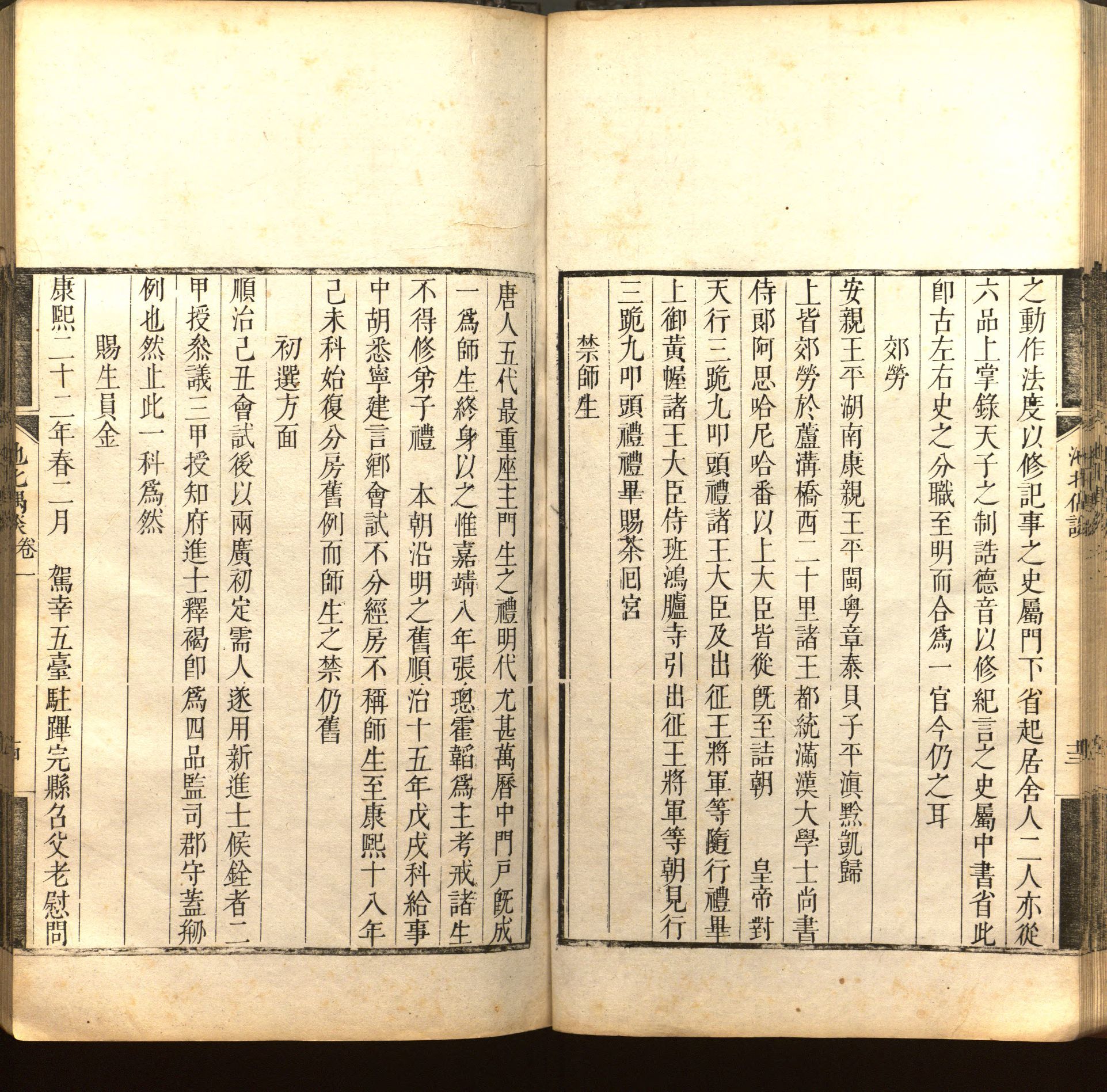

Fig. 5. Two pages from a 17th-century biji; the entry-based structure typical of the genre is clearly visible here. Wang, Shizhen, Tinglun Zhi, and Chinese Rare Book Collection. Chi Bei Ou Tan: Er Shi Liu Juan. [Fujian Tingzhou fu: Zhi Tinglun, Qing Kangxi 30 nian, i.e, 1691] Image. https://www.loc.gov/item/2012402038/.

In their free-ranging, unsystematic attention to a wide range of subjects — and especially their interest in the particular rather than the universal — biji seem quite similar to Renaissance European miscellanies. Like their European counterparts, they too have often been interpreted not merely as a genre, but also as emblematic of an intellectual current that offered a challenge to the systematizing mainstream of their day. In an article on Zhang Lei’s Mingdao Zazhi, the intellectual historian Peter Bol takes precisely this position, if tentatively:

“I shall suggest that the pi-chi is as representative of the new literati culture of the Sung dynasty as Neo-Confucianism and Wang An-shih’s great plans for political reform [i.e., the grand, systematic approaches that characterized the mainstream of 11th century thought] but that it represents a very different stream. It stands against philosophical systems and authority from above.”14

“The pi-chi is a work as much from the bottom up as the top down, but it is not really a work of persuasion at all. Instead, it draws attention back to the diversity and particularity of actual phenomena and experience and it contradicts the politicians and the philosophers who believed they could understand history, the Classics, and man’s relation to the cosmos in a systematic way and redirect human affairs accordingly.”15

Despite the breadth of his claims, however, Bol offers such speculation on the basis of almost no clear evidence that Zhang or the other biji writers he discusses actually harbored any resentment toward or desire to reject systematization. It is, rather, their inversion of the systematic approach through their un-systematic attention to the particular that is taken as a sign of implicit opposition. Earlier in his article, however, Bol takes a gentler stance, and makes a suggestion that might be helpful in making sense of texts like Zhang’s biji or Ms. Fr. 640: “One sometimes suspects that the heterogeneous character of the pi-chi format is a tactic meant to free the author from having to mean something in a larger sense.”16 Perhaps both in Renaissance Europe and in Song China it was the freedom such genres as the miscellany and the biji permitted to pursue knowledge in provisional, fragmentary ways in eras when systematicity was highly prized that led them to become so ubiquitous.17

_______

In sum, then, both in the case of Ms. Fr. 640 and of Song biji like Zhang Lei’s, perhaps the best way forward is, as Olivia Branscum suggests in her essay on Ms. Fr. 640, to to reject “the choice between the encyclopedic and miscellaneous paradigms.”18 Might it be that in trying to fit Ms. Fr. 640 into the encyclopedic vs. miscellaneous discourse — or to frame biji as inherently opposed to systematic approaches to knowledge — we are failing to realize that their authors’ interests lay elsewhere? Although not as satisfying as assigning these texts and their authors clear positions in intellectual debates, it might be that the relationship between practical, material knowledge and overarching, coherent understandings of the cosmos was not much on their minds. It need not have been that they felt this relationship unimportant or not worth articulating; they may simply have been content to leave this articulation for another time or another person, while pursuing their individual interests with little direct consideration of their significance to any overarching scheme. Even if this were so, however, the larger contexts in which texts like Ms. Fr. 640 and Zhang Lei’s Mingdao Zazhi emerged suggest that, if in ways that are still unclear, these texts were not merely the byproducts of the isolated whims and interests of their authors. The interest in both Renaissance Europe and Song China in particulars instead of universals and description in place of synthesis can be seen as a significant intellectual shift in the treatment of natural phenomena. What might have triggered such a shift in such remarkably similar directions in times and places as far removed as these is a question worthy of further comparative research.

Neil Kenny, The Palace of Secrets: Béroalde de Verville and Renaissance Conceptions of Knowledge (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), 43. ↩︎

Ibid., 1. ↩︎

Olivia Branscum, “Necessary Particulars: Philosophical Reflections on Making and Knowing with Ms. Fr. 640,” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, ed. Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020), https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_069_fa_18. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/2ap7-d967. ↩︎

“As small peddlers lay open small wares in order to buy richer ones & to profit more and more, so I, from a desire to learn, am exposing what little is in my workshop to have it receive, through a common commerce of letters, much rarer secrets from my benevolent readers” - BnF Ms. Fr. 640, fol. 162r, “For the workshop.” ↩︎

Vera Keller, “An Active Form of Education: The Boutique and the Tablet of Cebes,” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020) https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_330_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/dy3g-xm85. ↩︎

Image, citation, and caption are from Keller, “An Active Form of Education.” ↩︎

It is, however, possible that this concentration of content on a single set of closely-related topics was the result of the author-practitioner having consulted another text dealing with or a practitioner of the craft in question. ↩︎

Branscum, “Necessary Particulars.” ↩︎

Biji were already being written more than half a millennium before the Song, though they became much more common over time and also changed significantly in character. The miscellany-like character of many Song biji is not as apparent in pre-Song examples of the genre; an interest in the material world, in particular, seems to have been new. ↩︎

For more information on the textual history and significance of the Zuo commentary, see the introduction to the text by Durrant, Li, and Schaberg in their recent translation. Stephen W. Durrant, Wai-yee Li, and David Schaberg, trans., Zuo Tradition / Zuozhuan : Commentary on the “Spring and Autumn Annals.” 3 vols., Classics of Chinese Thought (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016). ↩︎

“明道雜誌,” Chinese Text Project, accessed June 20, 2021, https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=865185. ↩︎

Peter Bol, “A Literati Miscellany and Sung Intellectual History: The Case of Chang Lei’s Ming-tao tsa-chih,” Journal of Sung-Yuan Studies 25 (1995), 148. ↩︎

Ibid., 150-1. ↩︎

Ibid., 125. ↩︎

Far more, of course, could be said about the authors of biji and their reasons for writing them, but fuller consideration of the similarities and differences between European miscellanies and Chinese biji must, for the time being, be left for future work. ↩︎

Branscum, “Necessary Particulars.” ↩︎