Understanding Natural Things in the World and the Workshop

Anna Christensen

Summer 2021

The lifecasting and preservation practices that appear in BnF Ms. Fr. 640 are a window into the understanding of the natural world through craft practice during the sixteenth century. Animals that appear as casts or natural historical specimens in the manuscript include frogs and toads, snakes, lizards, turtles, flies, spiders, beetles, crabs, crayfish, bats, rats, cats, and birds of various kinds. The attention paid to these commonplace animals and their representation through craft practices can shed light on the way nature was imagined and came to be known during this period. Through certain choices the author-practitioner makes around the posing, juxtaposition, and display of his dried animal specimens and life casts, we can begin to get at his attitude towards representing the natural. More than just seeking to imitate the natural world, the author-practitioner’s craft reflects both artistic considerations and attempts to understand how animals interact with one another and with the world around them.

It becomes clear through reading the manuscript that the author-practitioner is working with a different set of conceptions about nature as a category than we typically use today. The question of whether he has a larger view about what nature is, or whether he is simply seeking to understand and recreate living things which possess the quality of being “natural” is not always evident. Isabella Lores-Chavez, in her paper “Imitating Raw Nature,” describes the author’s orientation towards the natural world as primarily focused on uncovering a set of processes of creation which could then be imitated. Her analysis of the author-practitioner’s use of terminology concludes that he discusses living things as possessing a quality of “the natural” (perhaps in reference to the forces that shaped them) rather than simply belonging to the category of “nature.” She notes that often the author’s use of terminology seems to locate nature in the raw material of a thing and to highly value the physical object as representation or accretion of natural properties.

The natural history and lifecasting projects that the author of the manuscript lays out are reminiscent of the work of other artists of the Renaissance such as Bernard Palissy (c.1510-c.1589) and Wenzel Jamnitzer (c.1507-1585), who created elaborate scenes of ceramic and metal animals from lifecasts, often to decorate various forms of tableware. These forms of artistic practice were both decorative and natural historical, often seeking to blur the boundaries between the work of the human hand and that of nature. While the lifecasting instructions laid out by the author of our manuscript tend not to be explicitly situated as part of a grander decorative project, they do seem to combine aesthetic sensibilities with attempts to express knowledge about nature. As Pamela Smith points out, the practices described in this manuscript contain uniquely “extensive observations of animal behavior,” often connected to its instructions on lifecasting.1

In some instances, the author of the manuscript explicitly bases his choices about display of animals on practical aesthetic concerns. The author in his entry “Various animals entwined” (folio 133v) notes, “You can entwine a snake with a lizard, one biting the other, or a snake that eats a frog or a wall lizard & suchlike. . . These entwinings are also made to cover a wound or fault in the animals, which one usually wounds when one catches them.” The author at other points suggests one might want to cast “female lizards entwined while biting each other” or “snakes bound together in embraces of love” when they are small (folio 122r).

While the author explicitly points out how the choice to pose multiple lifecast specimens together can be practical in nature, he does often mention the difficulty of uncovering (removing from the mold) certain entanglements like the entwined female lizards. (On practical concerns around casting a lizard, see Andrew Lacey and Siân Lewis, “In Pursuit of Magic.” The fact that such arrangements of multiple animals would typically make the casting and mold-removal process more difficult than casting a single animal, indicates that it has a value other than the practical one of covering what the author-practitioner refers to as “imperfections,” such as wounds in the animals that result from how they have been captured or killed.

The vision of the natural world that this variety of poses presents is one that runs along a spectrum from violent antipathy at one end to affectionate sympathy at the other. In fact, this view is further laid out in the next entry in the manuscript. In the entry “Flower in the mouth of the snake,” (folio 122r) the author suggests, “If you want to put in the mouth of the snake some flower or some branch of a plant which contains the antidote against its bite, take a little branch, as best arranged as you can find, & pose its stem into its mouth.” The juxtaposition of a snake with a harmless flower, or with the botanical antidote to its own venom, suggests a natural world that exists as a source of danger as well as of aesthetic pleasure, and where naturally occurring poisons have naturally occurring antidotes. (See also: Fabien Noirot’s essay on lifecast snakes, “Molding, Modeling, and Repairing: Lifecast Snakes Modeled in Black Wax.”)

The association of snakes and their venom with antidotes to poison during this period is reflected in other objects of human artifice such as the coral tree described by Martin Kemp which had “serpents’ tongues” (really fossil sharks’ teeth) hanging from its branches, which could be dipped in food or drink to act against poison. Kemp points to objects such as these as “a conscious blurring of the demarcation between the products of nature and man.”2

In addition to understanding and representing nature, the author-practitioner seeks to influence, and even modify, nature. The author provides a particularly compelling picture of the ability of human artifice to both imitate and influence nature in his entry on “Catching birds” (folio 160v). After instructing the reader to skin birds after they have molted in winter and to dry them out and stuff them, he says “Then arrange them on the trees, & have someone who sings, & you will gather them & catch many.” The image of dozens of stuffed birds tied to a tree, with a singer hiding below while trying to entice live birds to land is a distinctly comical one. But the author-practitioner seems to take it in all seriousness as a way to use natural historical specimens to beget a meal, or perhaps more natural historical specimens.

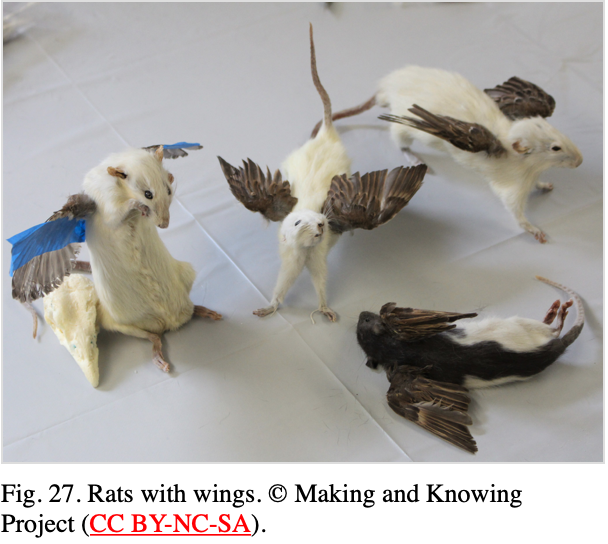

The entry “Animals dried in an oven” (folio 130r), begins to hint at practices that go beyond the imitation of nature and move into the realm of imagination. After describing how to dry and display a small cat, the author notes, “One gives it a painted tongue, horns, wings & similar fancies. Thus for rats & all animals.” (For more on this entry, see Divya Anantharaman’s essay, “Animals Dried in an Oven.”)

Though moving away from representative nature, this practice is still, I would argue, a natural historical one. Here the author-practitioner is exploring the power of the human hand to enhance natural objects and hybridize species, an artistic project not uncommon during the sixteenth century as new and strange animals were encountered and imagined in the conquest of the Americas3 and as books such as Ovid’s Metamorphosis were widely read. This project, along with the lifecasts that the author-practitioner makes, can together be characterized as part of an effort to “demonstrat[e] the human ability to imitate the transformative powers of nature.” 4 In seeking to push the boundaries of what nature can be, the author-practitioner is still investigating what nature is, and how it functions in tandem with and in relation to humanity. What the author of Ms. Fr. 640 brings to these questions is a work that uniquely combines observation and care of live animals with detailed instructions in lifecasting and occasionally taxidermy, and subsequent suggestions for how to pose the animals of interest that point to observations about their role in nature. It is through these ideas about how crafted animals should be posed that the author-practitioner’s observations of life become melded with the art of the human hand, by which evidence of both nature and craft are displayed.

Pamela H. Smith, “In the Workshop of History: Making, Writing, and Meaning,” West 86th 19, no. 1 (2012): 4-31. ↩︎

Martin Kemp, “‘Wrought by No Artist’s Hand’: The Natural, the Artificial, the Exotic, and the Scientific in Some Artifacts from the Renaissance,” in Reframing the Renaissance: Visual Culture in Europe and Latin America, 1450-1650, ed. Claire Farago (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995). ↩︎

Dániel Margócsy, “The Camel’s Head: Representing Unseen Animals in Sixteenth-century Europe,” in Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 61 (2011): 61-85. ↩︎

Pamela H. Smith and Tonny Beentjes, “Nature and Art, Making and Knowing: Reconstructing Sixteenth-Century Life-Casting Techniques,” Renaissance Quarterly 63, no. 1 (2010): 128-79. ↩︎