Languages and Linguistic Agency in Ms. Fr. 640

Gilles Narcy

Spring 2023

HIST GU4962: Making and Knowing in Early Modern Europe: Hands-On History

Introduction: Languages as practical knowledge

This essay focuses on the role played by languages in Ms. Fr. 640. Although written in French, as its call number in the Bibliothèque nationale de France’s catalogue indicates, it contains several occurrences of other languages. Extensive scholarship has been dedicated to artisan authors and the rise of books of recipes in the early modern era, focusing on the difficulties and paradoxes of putting embodied, practical knowledge into writing.1 The perspective adopted in this essay is to approach writing, and more specifically the use of different languages in various contexts, as a skill and a practical process itself. My main contention, drawn from sociolinguistics, is that languages, rather than neutral and substitutable vehicles for communication, carry different meanings and implications in and of themselves. They coexist and define themselves in relation to each other inside a social space that can be described alternatively as an ecology2 or as a market3. The use of each language produces precise textual effects in the manuscript, whether they are purposely intended by the author-practitioner or not.

In practical metaphors, languages can be understood as materials with different properties that influence the information they carry. They can also be conceived as tools, used by the author-practitioner to achieve textual goals. In this perspective, languages should be considered separately as well as in relation to each other. The historian Paul Cohen reminds us that plurilingualism was the rule for all in Renaissance France, at the same time, drawing attention to the fact that a sociolinguistic hierarchy separated and classified the existing languages. But while historians have extensively studied the relation of language to culture, politics,4 and even the sciences,5 its relationship in the crafts and sciences remains largely overlooked. Ms. Fr. 640 is a good case study to examine the use of language by early modern craftsmen.

The non-French languages in the manuscript belong to three different categories: ancient languages (Latin and Greek), foreign languages (Italian and German), and local languages (Occitan and Poitevin).6 This group of languages, as I will try to demonstrate, is not merely conventional or coincidental: ancient, foreign, and local are not only linguistic categories, but, rather, to some extent epistemological. Ancient languages are linked with learned knowledge, foreign languages with the circulation of artisanal practices, and local languages with experimental accounts. The boundaries between each of these groups, however, are far from sharp, and their realms often blur.

In what follows, I will first present a dataset for non-French occurrences in Ms. Fr. 640, built with Excel with the valuable help of Naomi Rosenkranz and Terry Catapano, to whom I am sincerely grateful. I will show how we can use this dataset in combination with other quantitative tools to offer a computational approach to linguistic tags in the manuscript, an approach that paves the way for qualitative analysis.

Each language can be approached individually or thematically. Thus, the question was whether to follow language groups or thematic sections which show intersections between various languages: the author-practitioner’s literacy, or the various names of materials, plants, and tools, for example. As the dataset is built upon occurrences per language, I chose to delve successively on each of my three groups of ancient, foreign, and local. Nonetheless, these themes will be tackled repeatedly throughout the essay in a comparative perspective between individual languages.

Building and exploiting a dataset on languages in Ms. Fr. 640

I started building the dataset of languages in Ms. Fr. 640 manually. Using the digital edition, I entered every recipe containing an occurrence of non-French language. For each, I entered the language, the folio number, the English title of the recipe, the semantic tag(s) of the recipe, and the number of linguistic tags (i.e., the number of occurrences of each language per recipe). Terry Catapano and Naomi Rosenkranz then very generously helped me to improve my dataset using the xml code of the edition: instead of having one line per recipe, I now have one line per occurrence. The dataset in its current version also provides the three closest parent tags for every occurrence, as well as the text itself on the same line. This first version was based on the English translation version of the manuscript. I exported the code of the French diplomatic version to Excel to produce a second one. There was no major difficulty, except for some special characters and recipe titles which were lost in the process and that I had to add again manually. The same can obviously be done for the French normalized version of the text.

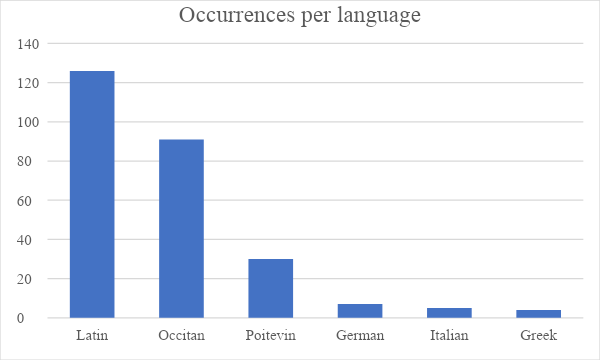

Assembling the data by hand already gave me a good sense of the linguistic patterns for every language. The most instinctive use of the dataset was to plot a chart of the occurrences of every non-French language in the manuscript, which gives a clear visualization of the gap between three most frequent languages on one hand (Latin, Occitan, and Poitevin), and three rarest ones on the other (German, Italian, and Greek) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Number of occurrences per language

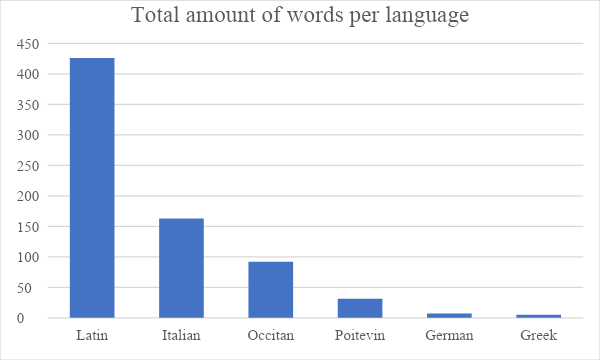

However, a second chart (Fig. 2) reveals that Occitan and Poitevin occur only as single words, whereas Italian accounts for full sentences. It demonstrates that a close reading of the recipes remains necessary to interpret the data created.

Fig. 2. Total number of words per language

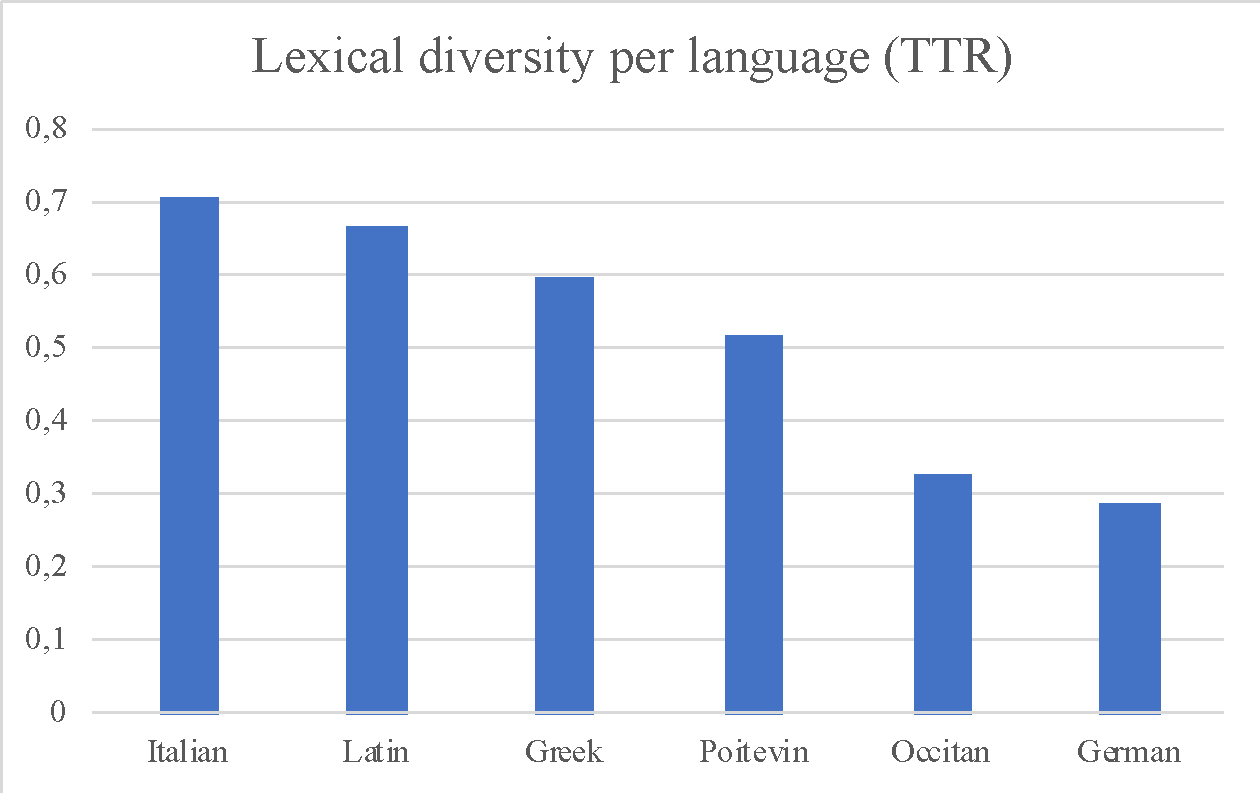

I further relied on the extensive computational research that has been done on the manuscript by Clément Godbarge, Roni Kaufman, and Dana Chaillard.7 I use their charts extensively throughout this essay. I tried to implement the correlations between languages and semantic tags with a focus on linguistic diversity: using Professor Alex Reuneker’s free calculator online, I generated lexical diversity scores for each language. The score corresponds to a Type-Token ratio (TTR): the number of single-occurring words divided by the total number of words (Fig. 3). 1 represents a text in which every word occurs only once. TTR is one of the most basic indicators of linguistic diversity. Despite its lack of precision, it gives a sense of the lexical variety of the author-practitioner for each language. In the case of German, I uniformized the spelling of “Spat” into “Spalt” to produce a coherent result. I then proceeded to plot the scores into a single bar-chart.

Fig. 3. Lexical diversity per language (TTR)

The results show that there is no association between frequency of occurrences and diversity: Occitan is the second most frequent language but has the second lowest lexical diversity score, while Italian has the highest score of all languages. As expected, there is, on the contrary, a strong association between the number of words and lexical diversity, especially when leaving aside the very small samples of German and Greek.

Such quantitative analysis is not a terminal point, however, but rather helps reveal unexpected patterns and possible reading paths for Ms. Fr. 640.

Latin and Greek: performing high knowledge

Ancient languages constitute the first group of non-French languages in the manuscript. In the sixteenth century, Latin and Greek were perceived as sharing several common features. First, they were the languages of classical knowledge from pagan as well as Christian Antiquity. Second, they were regarded, alongside Hebrew (a novelty of the sixteenth century for Christian scholars), as the most perfect languages, by far superior to any of the vernaculars. However, the relation between Latin and Greek was very much asymmetrical: while Latin was the language of religion, power, and science, widely spread among learned elites and taught in grammar schools, Greek was a scholarly knowledge that had been rediscovered in Western Europe during the fifteenth century only. Ms. Fr. 640 testifies to this asymmetry (Fig. 1).

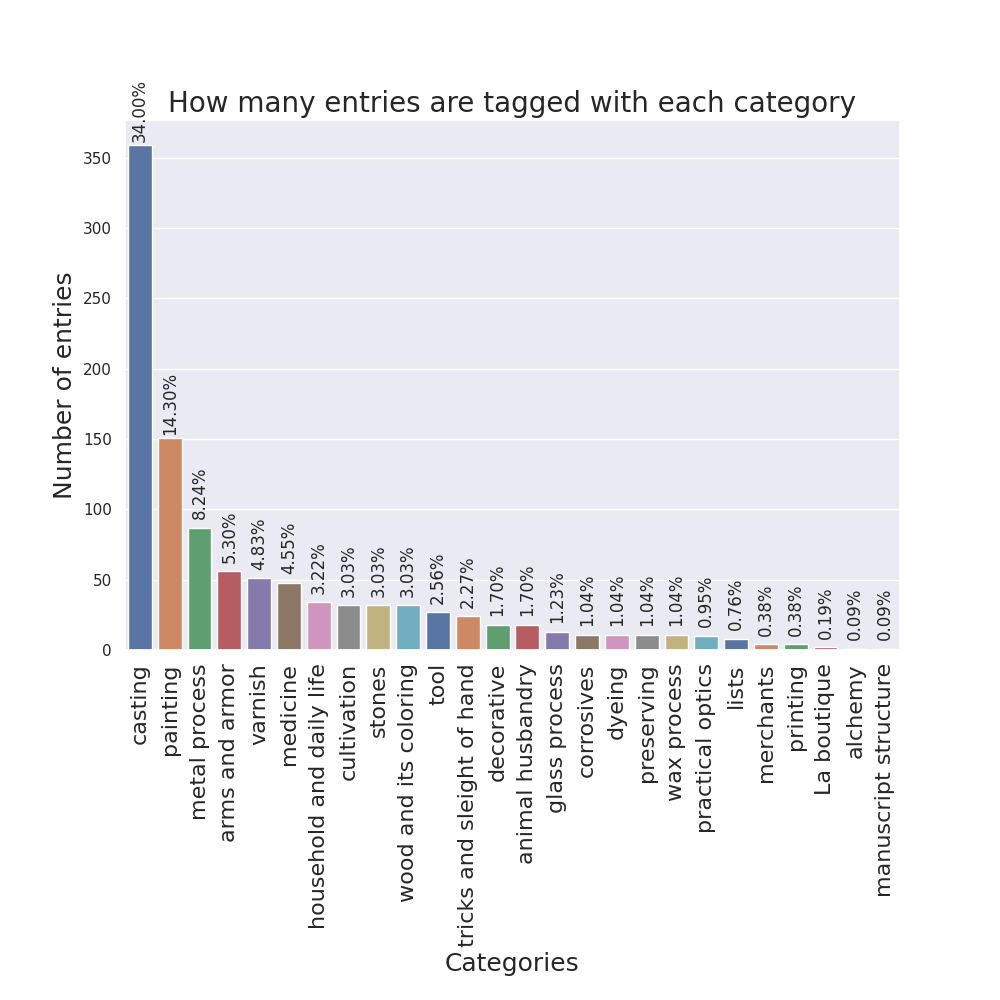

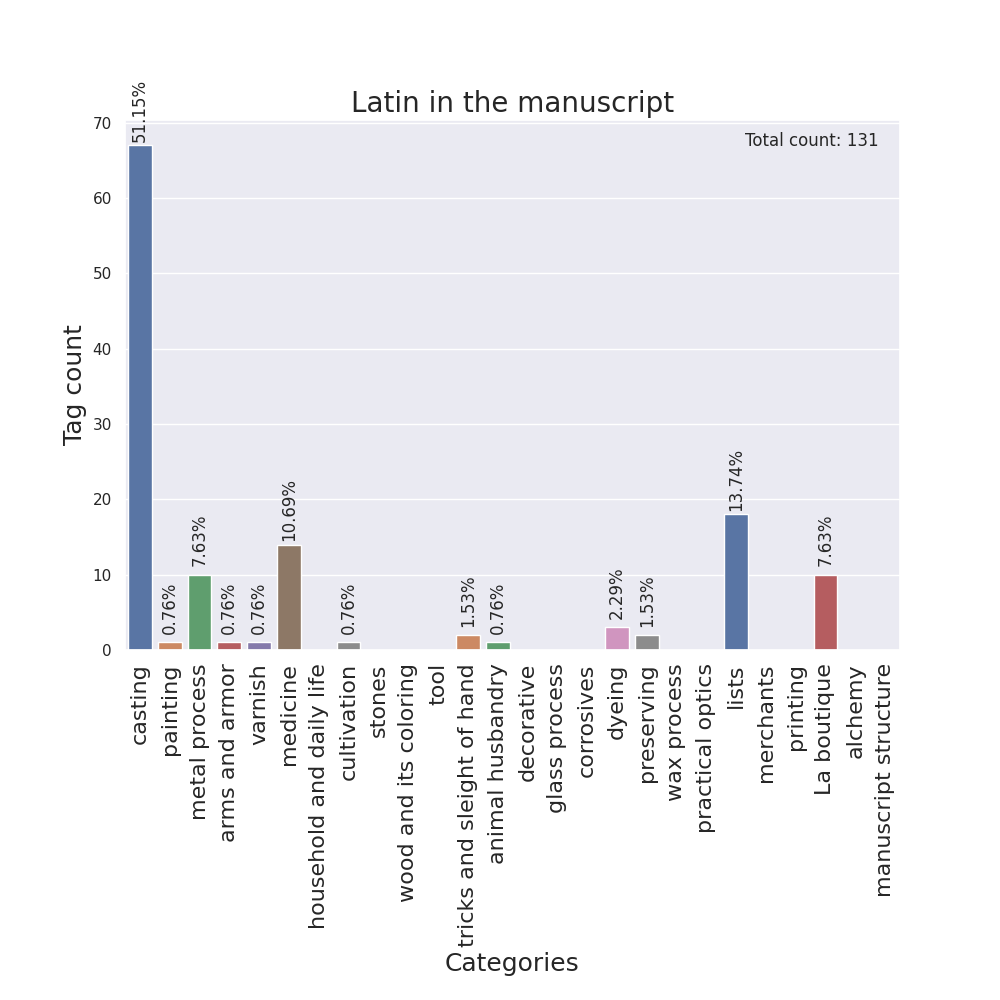

Comparing Naomi Rosenkranz’s general chart on the frequency of each semantic tag in Ms. Fr. 640 (Fig. 4) with Roni Kaufman’s bar charts (Fig. 5) on the correlation between language tags and semantic tags, we can observe that casting, which already amounts to 34% of the total entries, is overrepresented in Latin, with more than half of the occurrences. Medicine also has a strong association with Latin (10.69% against an overall 4.55%). On the contrary, painting (0.76% against 14.3%), cultivation (0.76% against 3.03%), and household and daily life (0% against 3.22%) are underrepresented. At first sight, Latin seems to be associated with high realms of knowledge: medicine was taught in the universities, and casting could have military applications8 or serve to create precious objects for a Kunstkammer. Common life, on the contrary, is poorly transcribed into the language of elites.

Fig. 4. How many entries are tagged with each category9

Fig. 5. Tag count: Latin in the manuscript10

Latin occurs in three different ways. First, in references or quotes, most of which have been identified by the digital editors of the manuscript. Even leaving aside the first folio, which contains a list of books to recover written by a different hand than the author-practitioner’s,11 Ms. Fr. 640 contains several titles of books and borrowed sentences in Latin, such as Henri Estienne’s translation of Herodotus, Flavius Josephus, Terence, and other classical authors. Some Latin quotes are also borrowed from modern authors, such as the Italian professor of medicine Girolamo Mercuriale in the “For preservation” entry (fol. 170r). Interestingly, these Latin references are to be found mainly in the programmatic entries “For the workshop” (fols. 162r and 166r). In fol. 166r, the author-practitioner reflects on how he should respond to a “jealous person” (“zélotype”) who would blame him for having only compiled recipes and not provided for new knowledge. His answer is taken from Terence: “nullum est jam dictum quod non dictum aut factum sit prius,” (nothing is said now that has not been said or done before). This is followed by a list of Latin authors who borrowed from Greek predecessors and by comparisons with weavers and masons as well, who use the materials of others to create new objects. It reveals that the author-practitioner’s practical epistemology is rooted in the same conservative and imitative culture of the humanists.

The author-practitioner uses Latin not only to defend his theory of knowledge, but also to describe practical processes. In fact, most Latin occurrences are names of materials. Quantitatively speaking, casting dominates, as Figs. 4 and 5 show, with two main materials: aes ustum (burnt copper) and above all crocum ferri (an iron additive). However, there is more variety in the use of Latin names for plants and organic materials in general, with a total of 10: pix Graeca, capillum Veneris, lapathum acutum, symphitum, consolida, semperviva, vermicularis, palma Christi, ranunculus, palta lupina. We can add to those, caput mortuum,12 a haematite pigment. Many of these materials, such as capillum Veneris (maidenhair fern), were common in Languedoc and could have easily been designated using vernacular names in French or Occitan. In this context, the use of Latin on the author-practitioner’s part could be linked with the rise of herbals, such as that of Ulisse Aldrovandi or Conrad Gessner’s Historia Plantarum (although it remained unpublished until the eighteenth century), and of natural history in general. Latin, here, conveys the learned character of several of the author-practitioner’s recipes, illustrating its role as a vehicle for knowledge in early modern Europe.

Latin proves useful to the author-practitioner not only to designate various materials, but also to give instructions and annotations about the processes he describes. Several technical terms or abbreviations in Latin, in fact, are recurrent throughout the manuscript: nota (“note”) occurs 6 times; ℞, abbreviation for “recipe” (“take”), 5 times; ana (“equally”), 2 times. The recipe “To make silver run” (fol. 120v) also contains the marginal annotation “Siscitatio [sic.] dubia,” meaning “dubious question,” although spelled wrong (“siscitatio” for “sciscitatio”).

Overall, the use of Latin in the manuscript is pervasive, whether to imitate learned culture and prove the learning of the author-practitioner or to describe precise materials and plants. In the era of print, names and processes tended to be standardized at a transnational level, an opposite trend to the rise of political nation states. The variety of ways in which the author-practitioner uses Latin shows its relevance in practical knowledge as much as in high culture. It enlarges Françoise Waquet’s traditional interpretation of Latin in early modern Europe, according to whom Latin survived thanks to three conservative elite institutions: schools, the Church, and scholarship.13 Ms. Fr. 640, on the contrary, provides an example of a transnational circulation of knowledge in Latin among practitioners rather than scholars, and of social imitation of cultural elites by a lower member of the social hierarchy.

Greek occurrences, on the other hand, are limited to two recipes only: “Snakes” (fol. 13v) and “For the workshop” (162r). In the latter, the author-practitioner uses the name Clio, the Greek muse of history, to refer to Herodotus’ Historia. The former entry, which has been extensively researched by Victoria Nebolsin, is short and seemingly odd.14 It indicates that snakes, if called with their Greek name, όφι, will flee. On the contrary, pigs called with their Greek name ïon will come. As far as literacy is concerned, it is evident that the author-practitioner had barely any notion of Greek: his orthography of single words is not correct, and the first term only is spelled in Greek alphabet. Nonetheless, the recipe can still be regarded as a form of reenactment of ancient Greek knowledge. It is probably inspired by an episode of Plutarch’s Moralia, also mentioned in Giovanni Battista Gelli’s La Circe (1549). Gelli was himself an author-practitioner: trained as a shoemaker in Florence, he published books dealing with crafts as well as philosophical dialogues in the humanistic tradition. It is likely that Plutarch’s anecdote was borrowed from him, but it should also be noted that the Greek philosopher was a very popular author in Renaissance France. The passage from the Moralia is a parody of Odyssey, X: Odysseus engages in dialogue with a swine philosopher, Gryllus, who advocates for the superiority of animals over humans since they possess crafts by nature and do not need to acquire them through training. Nebolsin interprets this unacknowledged reference as an endorsement of Gryllus’ praise of natural skill on the author-practitioner’s part. However, it is also worthy to note that the “Snakes” entry on fol. 13v does not deal with crafts or skills as much as with language and literacy. Why should animals respond to Greek rather than to French, Latin, or any other language? My hypothesis is that the author-practitioner regards Greek as a language with a magical aura, associated with ancient, philosophical, and also occult knowledge. The ability to command animals through language is in fact a recurring magical skill in different cultures and societies.

The “Snakes” entry demonstrates that ancient languages carry supernatural implications. In Saussurian terms, they do not serve only as signifiers for a signified such as tools or materials; they are a material element of the recipe. This is also the case in the entry “Against burns, excellent” (103r), which contains a recipe for a healing salve that must be used while reciting the paternoster prayer in a precise order.15 The words “pater noster” have been encoded as French and not Latin in the manuscript, on the ground that it was indeed a common phrase. Nonetheless, the prayer still had to be said in Latin, especially in a Catholic context. The prayer must be said in a precise rhythm, making the recipe akin to a religious ritual such as the Catholic Eucharist, where the transubstantiation occurs through the combination of the priest’s gestures and the uttering of the “words of institution.” Both entries pertain to what linguist James L. Austin famously called “performativity”: the use of language to act rather than to state.16 But in the context of practical knowledge, as demonstrated by these uses in Ms. Fr 640, languages are not only performative, rather, they are put on the same level as other materials. It can thus be contended that under certain circumstances, such as the supernatural use of Latin and Greek, languages possess their own form of materiality, where Latin is used in the form of a prayer inspired by Church rituals that helps effect a material transformation, Greek is the language of performativity that compels the action of a physical being.

On an anthropological level, the Latin-Greek couple thus replicates to some extent the duality of religion and magic.17 This divide, however, should not be overemphasized. In fact, the recipe “For melting or transmuting a jewel put inside a box” (fol. 34v) uses Latin in a magical context18: to perform the transmutation, one is supposed to say “inhonorificabilitidinitatudinibus” before performing the trick. Still, magic in this sense differs from the “Snakes” recipe: macaronic Latin is used in a sleight of hand to deceive the spectator into thinking that real magic is taking place. The fake and absurd Latin creates an effect of burlesque far from the sacredness of the paternoster prayer. Calling animals with their Greek names, on the contrary, implies supernatural powers, or rather ascribes to the animals’ nature what is usually regarded as the definition of humanity: language.

Italian and German: the geography of artisanal practices in early modern Europe

Italian and German are the only foreign languages in the manuscript. Their presence tells as much as the absence of others since it gives us a clue, in Carlo Ginzburg’s sense,19 of transnational circulation of artisanal knowledge at the time. Foreign languages were not taught at school in the sixteenth century and the author-practitioner, even if he had attended one, could only have been in contact with them through other craftspeople. While the absence of English should not be surprising, that of Flemish and Spanish must be questioned. Flanders was a major artistic and artisanal center in sixteenth-century Europe and several techniques described in the manuscript were also known in Flanders and the Netherlands. Spain, on the other hand, was at the height of its power under Philip II and had a growing influence on French domestic affairs during the final years of the Wars of Religion during the period the manuscript was written.20 It is even more curious since Toulouse is so close to Spain. While no general conclusion can be drawn from one single case, the fact that only Italian and German occur testifies to their primacy in crafts at the time.

The two languages differ widely in their variety and their uses in the manuscript. German occurs slightly more often than Italian: 7 vs. 5. However, German is only present in casting. In fact, out of 7 occurrences, the word “Spalt” (sometimes spelled “Spat”) is responsible for 6. Spalt was a powdered earth used in casting. The other German occurrence is “Stuf” (fol. 118r), a limestone which the author-practitioner uses in a grotto recipe. Sofia Gans concludes from the frequency of the word “Spalt,” an earth sourced in Augsburg, that German was the center of European casting for the author-practitioner, rather than Italy, as is usually assumed for sixteenth-century Europe.

While there are fewer Italian occurrences in the manuscript and none related to casting, they are considerably longer in length and broader in scope, with the second largest number of words after Latin. The only recipe which has been directly retraced to another text also comes from an Italian background: “For making very beautiful color of gold & of little expense” (fol. 76v).21 It is borrowed from the French translation of Alessio Piemontese’s Segreti.

The first occurrence of Italian is simply a book title on the first folio. But one recipe, “Purpurine” (43r), is written entirely in Italian:

℞ stagno dolce meza onca farlo fondere in un cochiaro depoi fonduto gectarly dentro una ℥ de ☿ mesedar insieme essendo freddo macinar supra il porfidio dapoi piglia una ℥ de sal armoniaco una ℥ de solfo del piu giallo que se possa troval macinar tutti duoi Et poi mesedar molto bene tutti gli matteriali sopradetti dapoi metter tutto insieme dentro un a pignatta sublimatorio di vetro tenerlo sopra picciol fuoco una hora & una hora un poco piu forte & una hora bonissimo fuoco Et sara fatto dapoi per adoper{ar}la datte il negro di resina con colla di pintori da pintar & per doi o tre volte fin a tanto che sia ben negro dapoi datte un poco di vernice Essendo secco datte a secco con ditto la purpurina dove vorrette tanto piu ne darette sara piu bello dapoi si volete datte vernice sopra.

The Italian is correct overall, although shaky at times and fraught with Hispanicisms: “meza” for “mezza,” “mesedar” for “mescolar” or “mischiar,” “que” for “che.”. The recipe was most probably copied or dictated to the author-practitioner, attesting to his acquaintance with Italian craftspeople whom he could have met in Toulouse or elsewhere.

The three remaining Italian occurrences can be grouped together as they

share a common particularity: they are the only titles in the entire

manuscript in a language other than French. As such, the Italian has

been left intact in the English translation. These are “To fire a

schioppo senza rumore” (fol. 55r), what we would call today a rifle

silencer; and “Onenev elbirro hcihw sllik fi eno spets no a draob ro a

ueirse purrits” (fol. 55r); and “A means di far correr lotnegra”

(fol. 123r). The second and third of these only seem incomprehensible

because their title must be read backwards, as follows: “Veneno orrible

[another Hispanicism] which kills if one steps on a board or a

stirrup” and “A means di far correr largento.” The use of backwards

writing, although very easily readable as a code, nonetheless connotes

the idea of secrecy: in the first case, because dealing with poison

(“veneno,” or venom); in the second, because the technique is known by

only a few goldsmiths and should remain such, or this is at least what

the author-practitioner paradoxically writes while proceeding to reveal

it (“This material should not be divulged, lest it be abused”). The

author-practitioner here was probably interested in giving the

impression of secrecy in order to appeal to his audience. It should not

be taken too literally, since real secrets would not have been so easily

divulged in print and would certainly have been encoded entirely,

whereas here the title or parts of it only are written backwards. Why,

then, choose to write in Italian to convey this idea? In late

sixteenth-century France, Italy was associated with secret and artifice

for many reasons. Italian influence on the arts and the royal court had

been important for several generations, from the School of Fontainebleau

during Francis I’s reign to the Italian courtesans surrounding the Queen

Mother Catherine de’ Medici. Italophilia and Italophobia ran parallel

and Italian influence became a political theme22: Italians, and

especially Florentines, were seen simultaneously as refined and

mischievous (even evil), mostly due to Machiavelli’s notoriety, whose

work, The Prince, was becoming a bestseller all around Europe at the

end of the sixteenth century.23 While admired by some, most regarded

him as the theorist of evil in politics, giving his name the aura it has

retained today. Catholics put him on the Index of prohibited books, but

Protestants nonetheless accused them of Machiavellism, which had become

an insult, especially after the Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre in 1572.

Italy was regarded as the country of artifice, secrecy, and conspiracy,

and the author-practitioner played with this reputation in his

manuscript.

Occitan and Poitevin: linguistic tools of experience

After Latin, Occitan and Poitevin are the most frequent non-French languages in Ms. Fr. 640. The literacy of the author-practitioner in these languages is harder to establish. On the one hand, they occur only in few words or expressions and present a low lexical diversity score (Fig. 3). However, all French people were at least bilingual in early modern France, even after the Villers-Cotterêts edict of 1539 which made French mandatory for every official, lay act. French became the dominant written language, but every region retained its own local idioms which were far more common in everyday life speech. As the identity and background of the author-practitioner remains obscure, we cannot know if he was a native speaker of Occitan, but the extent of Toulouse background he possesses allows us to make the hypothesis that he had at least solid notions of it. The choice of writing in French should thus be interpreted as an editorial choice as much as the consequence of his own literacy.

As far as the presence of Poitevin is concerned, we can assume that it came from the massive presence of Poitevin speakers in Toulouse. Poitevin was spoken roughly in a triangle area between Nantes in the North, Poitiers in the East, and Bordeaux in the South, not too far away from the Languedoc area of Toulouse. In French linguistics, it is considered a langue d’oïl, a Northern language, but takes some words from Occitan, which is a Southern langue d’oc.

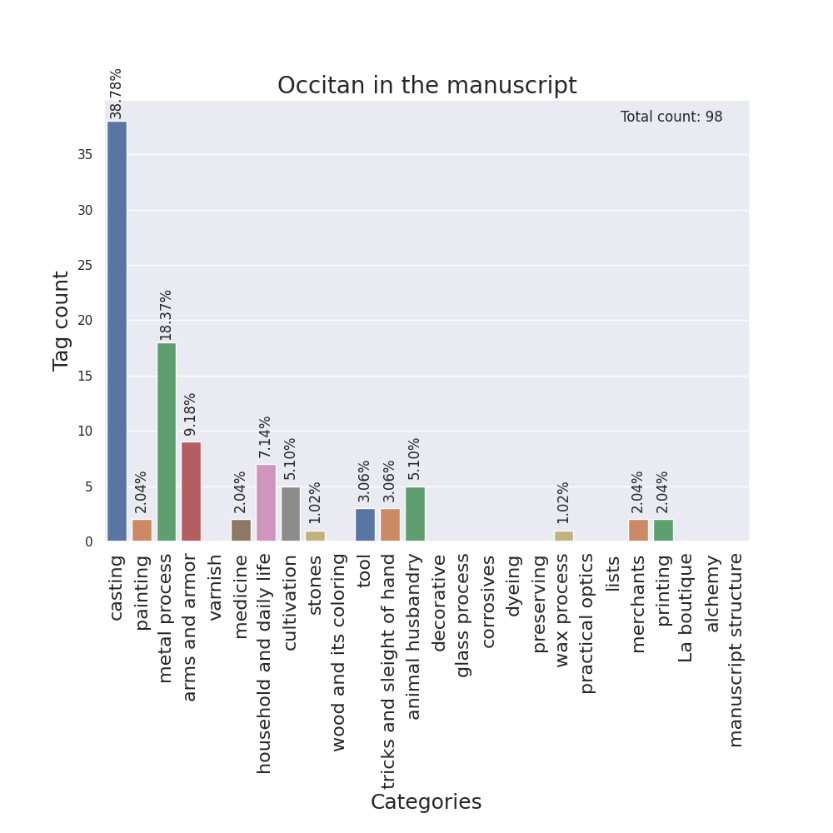

Fig. 6. Tag count: Occitan in the manuscript24

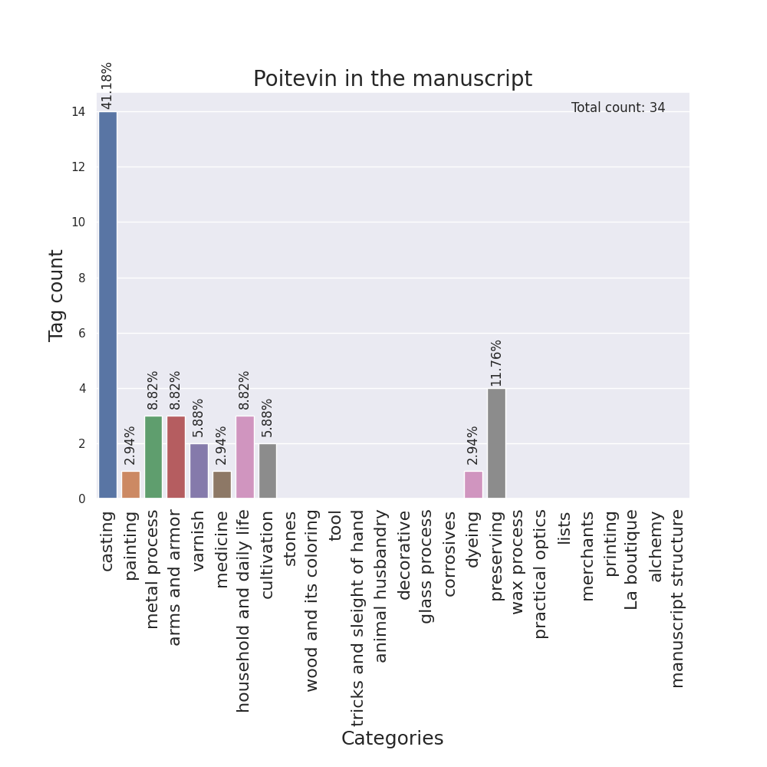

Fig. 7. Tag count: Poitevin in the manuscript25

Fig. 6 shows that Occitan is strongly associated with casting (38.7%) and metal processes (18.37%), with high percentages as well of entries dealing with arms and armor (9.18%), household and daily life (7.14%), and cultivation (5.10%). Fig. 7 shows that Poitevin’s profile is similar, with strong connections to casting (41.1%), household and daily life (8.82%), and cultivation (5.88%). As regional idioms, they can be linked to a form of local, native knowledge. There are no book titles in these languages, rather, they serve mainly to indicate some common tools, animals, or materials with the names that probably sounded more natural to the author-practitioner and/or to his informants. Compared to Latin, these occurrences attest to the permanence of vernacular knowledge in vernacular languages against the process of Latinization that we observed earlier in this essay. In Occitan, the overwhelming term is “crusol,” (crucible), a tool involved in dozens of recipes in the manuscript and occurring 54 times. The same is true for Poitevin with the word “tourtelle” (“cake,” in a very broad sense), which occurs 13 times. Here, the absence of complete sentences and the lack of linguistic diversity indicates that these terms come naturally to the author-practitioner. It allows him to give detailed, accurate accounts where the learned terms in Latin or French are missing or might be too vague and general.26

Conclusion: Making with languages

Although far from complete, this overview nonetheless reveals that the author-practitioner makes consistent and thoughtful use of the vast array of linguistic resources available to him in Renaissance France. Despite being a craftsman, he demonstrates a capacity to use various languages to achieve different goals. He exploits the possibilities of Latin as the language of knowledge and religion in his search for respectability, but also recurs to Greek as its occult and somehow mysterious pendant. The occurrences of German and Italian reveal his own involvement in transnational networks of crafts. To some extent, we can hypothesize that they are the traces left by wider circulations, which have been erased for the most part by translation and non-textual transmission. Occitan and Poitevin, finally, are very much associated with a handful of tools and materials: whether the author-practitioner himself originated from Toulouse or not, he needs the words of his professional environment to restitute his recipes and processes in the most accurate way.

This case study, as limited as it is, highlights two main aspects in the history of languages in sixteenth-century France. First, it confirms Paul Cohen’s thesis that France was a plurilingual country in which everybody made daily use of a surprising number of different languages. This does not mean that they were all equivalent; on the contrary, the hierarchy of languages and the struggle for linguistic respectability is essential in understanding linguistic practices, as Ms. Fr. 640 shows. Second, it widens the area of plurilingualism from cultural elites to other categories of society such as crafts practitioners, showing that Latin or foreign languages were not the exclusive domain of clerks and humanists. Even if they did not have the same linguistic training and capacities, practitioners such as the author of Ms. Fr. 640 were able to appropriate and use different languages according to their own strategic agendas.

Bibliography

Austin, J. L. How to Do Things with Words. 2d ed. The William James Lectures 1955. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975.

Burke, Peter, and Roy Porter, eds. The Social History of Language. Cambridge Studies in Oral and Literate Culture 12. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Balsamo, Jean. L’amorevolezza verso le cose Italiche: le livre italien à Paris au XVIe siècle. De lingua et linguis, vol. 2. Genève: Librairie Droz, 2015.

Balsamo, Jean. Les Rencontres Des Muses: Italianisme et Anti-Italianisme Dans Les Lettres Françaises de La Fin Du XVIe Siècle. Bibliothèque Franco Simone 19. Genève: Editions Slatkine, 1992.

Balsamo, Jean, Vito Castiglione Minischetti, and Giovanni Dotoli. Les traductions de l’italien en français au XVIe siècle. Biblioteca della ricerca 2. Fasano (Italie) Paris: Schena Hermann, 2009.

Barwich, Ann-Sophie. “Sleight of Hand Tricks.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_043_sp_16. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/rfq6-0k88

Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Symbolic Power. Translated by John B. Thompson. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Brunet, Serge. “Philippe II et la Ligue parisienne (1588).” Revue historique 656, no. 4 (2010): 795–844. https://doi.org/10.3917/rhis.104.0795.

Chaillard, Dana. “My Work at the Making and Knowing Project,” 2020. https://cu-mkp.github.io/sandbox/docs/Chaillard_final-report.html.

Chartier, Roger, Pietro Corsi, and Centre Alexandre Koyré, eds.Sciences et Langues En Europe. Paris: Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales, 1996.

Cohen, Paul. “Courtly French, Learned Latin, and Peasant Patois: The Making of a National Language in Early Modern France.” Ph.D., Princeton University, 2001. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (230830091).

Ginzburg, Carlo. Myths, Emblems, Clues. London: Hutchinson Radius, 1990.

Godbarge, Clément. “The Manuscript Seen from Afar: A Computational Approach to Ms. Fr. 640.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_301_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/nnyc-gd81.

Godbarge, Clément. “Visualizing Semantic Markup in BnF Ms. Fr. 640.” Clément Godbarge (blog), November 29, 2022. https://www.clementgodbarge.com/post/visualization/.

Kaufman, Roni. “My Work at the Making and Knowing Project,” 2020. https://cu-mkp.github.io/sandbox/docs/Kaufman_final-report.html.

Liu, Xiaomeng. “An Excellent Salve for Burns.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_080_sp_17. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/58dr-ns42.

Mauss, Marcel. A General Theory of Magic. London, Boston: Routledge and K. Paul, 1972.

Nebolsin, Victoria. “Animal Rationality in Ms. Fr. 640.” In Naomi Rosenkranz, Pamela H. Smith, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Terry Catapano, Research and Teaching Companion. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2024. https://teaching640.makingandknowing.org/resources/student-projects/sp22_nebolsin_victoria_final-project_animal-rationality/.

Palframan, Jef and Emily Boyd. “For Making Very Beautiful Color of Gold.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_507_ad_20.

Picot, Emile. Les Italiens En France Au XVIe Siècle. Memoria Bibliografica 25. Manziana (Roma): Vecchiarelli editore, 1995.

Rosenkranz, Naomi. “Understanding and Analyzing the Categories of the Entries in BnF Ms. Fr. 640,” 2021. https://cu-mkp.github.io/sandbox/docs/categories.html.

Smith, Marc. “Making Ms. Fr. 640.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_326_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/1wmr-2t14.

Smith, Pamela H. From Lived Experience to the Written Word: Reconstructing Practical Knowledge in the Early Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022.

Soll, Jacob. “The Reception of The Prince 1513–1700, or Why We Understand Machiavelli the Way We Do.” Social Research 81, no. 1 (2014): 31–60.

Taape, Tillmann. “‘Experience Will Teach You’: Recording, Testing, Knowing, and the Language of Experience in Ms. Fr. 640,” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_303_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/njnq-6q58.

Tavares, Jonathan. “Arms and Armor in Ms. Fr. 640.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_308_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/9rye-d152.

Waquet, Françoise. Latin, or, The Empire of the Sign: From the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century. London; New York: Verso, 2001.

Pamela H. Smith, From Lived Experience to the Written Word: Reconstructing Practical Knowledge in the Early Modern World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022). ↩︎

Paul Cohen, “Courtly French, Learned Latin, and Peasant Patois: The Making of a National Language in Early Modern France” (Ph.D., Princeton University, 2001), ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (230830091). ↩︎

Pierre Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, trans. John B. Thompson (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1991). ↩︎

Peter Burke and Roy Porter, eds., The Social History of Language, Cambridge Studies in Oral and Literate Culture 12 (Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987). ↩︎

Roger Chartier, Pietro Corsi, and Centre Alexandre Koyré, eds., Sciences et Langues En Europe (Paris: Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales, 1996). ↩︎

Marc Smith, “Making Ms. Fr. 640,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020), https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_326_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/1wmr-2t14. ↩︎

Dana Chaillard, “My Work at the Making and Knowing Project,” 2020, https://cu-mkp.github.io/sandbox/docs/Chaillard_final-report.html; Clément Godbarge, “The Manuscript Seen from Afar: A Computational Approach to Ms. Fr. 640,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project et al., https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_301_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/nnyc-gd81; Clément Godbarge, “Visualizing Semantic Markup in BnF Ms. Fr. 640,” Clément Godbarge (blog), November 29, 2022, https://www.clementgodbarge.com/post/visualization/; Roni Kaufman, “My Work at the Making and Knowing Project,” 2020, https://cu-mkp.github.io/sandbox/docs/Kaufman_final-report.html. ↩︎

Jonathan Tavares, “Arms and Armor in Ms. Fr. 640, in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project et al., https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_308_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/9rye-d152. ↩︎

Naomi Rosenkranz, “Understanding and Analyzing the Categories of the Entries in BnF Ms. Fr. 640,” 2021, https://cu-mkp.github.io/sandbox/docs/categories.html. ↩︎

Kaufman, “My Work at the Making and Knowing Project, https://cu-mkp.github.io/sandbox/docs/Kaufman_final-report.html. ↩︎

Smith, “Making Ms. Fr. 640,” https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_326_ie_19. https://www.doi.org/10.7916/1wmr-2t14. ↩︎

The translation for most of these terms can be found in the Glossary of Secrets of Craft and Nature: https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/folios/1r/f/1r/glossary. ↩︎

Françoise Waquet, Latin, or, The Empire of the Sign: From the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century (London; New York: Verso, 2001). ↩︎

Victoria Nebolsin, “Animal Rationality in Ms. Fr. 640,” https://teaching640.makingandknowing.org/resources/student-projects/sp22_nebolsin_victoria_final-project_animal-rationality/. ↩︎

Xiaomeng Liu, “An Excellent Salve for Burns,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project et al., https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_080_sp_17. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/58dr-ns42. ↩︎

J. L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words, 2d ed., The William James Lectures 1955 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975). ↩︎

Marcel Mauss, A General Theory of Magic (London; Boston: Routledge and K. Paul, 1972). ↩︎

On tricks in Ms. Fr. 640, see Ann-Sophie Barwich, “Sleight of Hand Tricks,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project et al., https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_043_sp_16. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/rfq6-0k88. ↩︎

Carlo Ginzburg, Myths, Emblems, Clues (London: Hutchinson Radius, 1990). ↩︎

Serge Brunet, “Philippe II et la Ligue parisienne (1588),” Revue historique 656, no. 4 (2010): 795–844, https://doi.org/10.3917/rhis.104.0795. ↩︎

Jef Palframan and Emily Boyd, “For Making Very Beautiful Color of Gold,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project et al., https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_507_ad_20. ↩︎

On this topic, see Jean Balsamo, Les Rencontres Des Muses: Italianisme et Anti-Italianisme Dans Les Lettres Françaises de La Fin Du XVIe Siècle, Bibliothèque Franco Simone 19 (Genève: Editions Slatkine, 1992); Jean Balsamo, L’amorevolezza verso le cose Italiche: le livre italien à Paris au XVIe siècle, De lingua et linguis, vol. 2 (Genève: Librairie Droz, 2015); Jean Balsamo, Vito Castiglione Minischetti, and Giovanni Dotoli, Les traductions de l’italien en français au XVIe siècle, Biblioteca della ricerca 2 (Fasano (Italie) Paris: Schena Hermann, 2009); Emile Picot, Les Italiens En France Au XVIe Siècle, Memoria Bibliografica 25 (Manziana [Roma]: Vecchiarelli editore, 1995). ↩︎

Jacob Soll, “The Reception of The Prince 1513–1700, or Why We Understand Machiavelli the Way We Do,” Social Research 81, no. 1 (2014): 31–60. Shakespeare’s plays such as Henry VI or The Merry Wives of Windsor testify to a similar twist in Machiavelli’s reception in English culture at the end of the sixteenth century. ↩︎

Kaufman, “My Work at the Making and Knowing Project,” https://cu-mkp.github.io/sandbox/docs/Kaufman_final-report.html. ↩︎

Kaufman, “My Work at the Making and Knowing Project,” https://cu-mkp.github.io/sandbox/docs/Kaufman_final-report.html. ↩︎

On writing down experience in Ms. Fr. 640, see Tillmann Taape,“‘Experience Will Teach You’: Recording, Testing, Knowing, and the Language of Experience in Ms. Fr. 640.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project et al., https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_303_ie_19. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/njnq-6q58. ↩︎