Counterproofing: Reproduction and Theft in Early Modern Print Culture

Theodora Bocanegra Lang

Spring 2022

Making and Knowing in Early Modern Europe: Hands-On History

In an entry of BnF Ms. Fr. 640 entitled “Counterproofing” (folio 51r, the author-practitioner provides the reader with instructions on how to copy a print using a method of the same name that entails wetting the print and pressing it onto a fresh piece of paper in an attempt to dampen the ink and ultimately transfer the image. Part of the author-practitioner’s recommended process involves burnishing the back of the page with a tooth or glass, which can leave indentations or marks on the paper. In this entry there is a particularly curious sentence: “And if you want this not to be known, if by chance, you borrowed the piece, moisten the paper, and the polishing that the burnisher has made on the back, which shows what has been done, will not be known.” Not only is the author-practitioner sharing how to counterproof, he is teaching something potentially nefarious: how to steal and not get caught. This essay asks the question of why might a craftsman in the sixteenth century, like the author-practitioner or his projected reader, want to steal a print, copy it, and surreptitiously return it.

To answer that question, first we must find why someone might want to copy a print to begin with. As Renaissance print scholar Ad Stijnman writes, counterproofing was an “ideal way of replicating a plate in order to extend the print run.”1 If the plate or matrix became damaged or was used to the point of destruction, a printer could take a finished print and reverse engineer another iteration of the plate, so as to continue printing. As is demonstrated by Nicole Bertozzi’s essay “Transferring Images” (https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_067_fa_18), counterproofing is particularly useful for this task because it preserves the original image, instead of other replicating techniques that destroy the original.2 This might allow the printer to make any tweaks or minor changes to the new print, and ultimately new plate, while still being able to reference the original. This technique also saves time: one might otherwise have to copy the original image by redrawing it from scratch. Counterproofing, even if incomplete, provides at least a sketch to start with.

The objective of extending a print run assumes that the printer owns the original print, that it is of his own making and he seeks to replicate it to continue his own ends of selling it. In the sixteenth century, however, forging or copying the works of others was a fairly common practice, sparking debates on authorship and ownership. Historian Brenda Hosington points out that “the identity of the author, often absent from medieval works, was given increasing prominence in the early modern book.”3

During this time, ideas about image originality, copies, and forgeries were similarly changing. Famed painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) was particularly bothered and subsequently vigilant about copies of his work, for good reason. A prolific artist, Dürer’s work was copied and forged as early as 1494.4 He famously included a notice at the beginning of one work, addressing would-be forgers. The colophon of The Life of the Virgin (1511) warns:

Beware, you envious thieves of the work and invention of others, keep your thoughtless hands from these works of ours. We have received a privilege from the famous emperor of Rome, Maximilian, that no one shall dare to print these works in spurious forms, nor sell such prints within the boundaries of the empire…. Printed in Nuremberg, by Albrecht Durer, painter.5

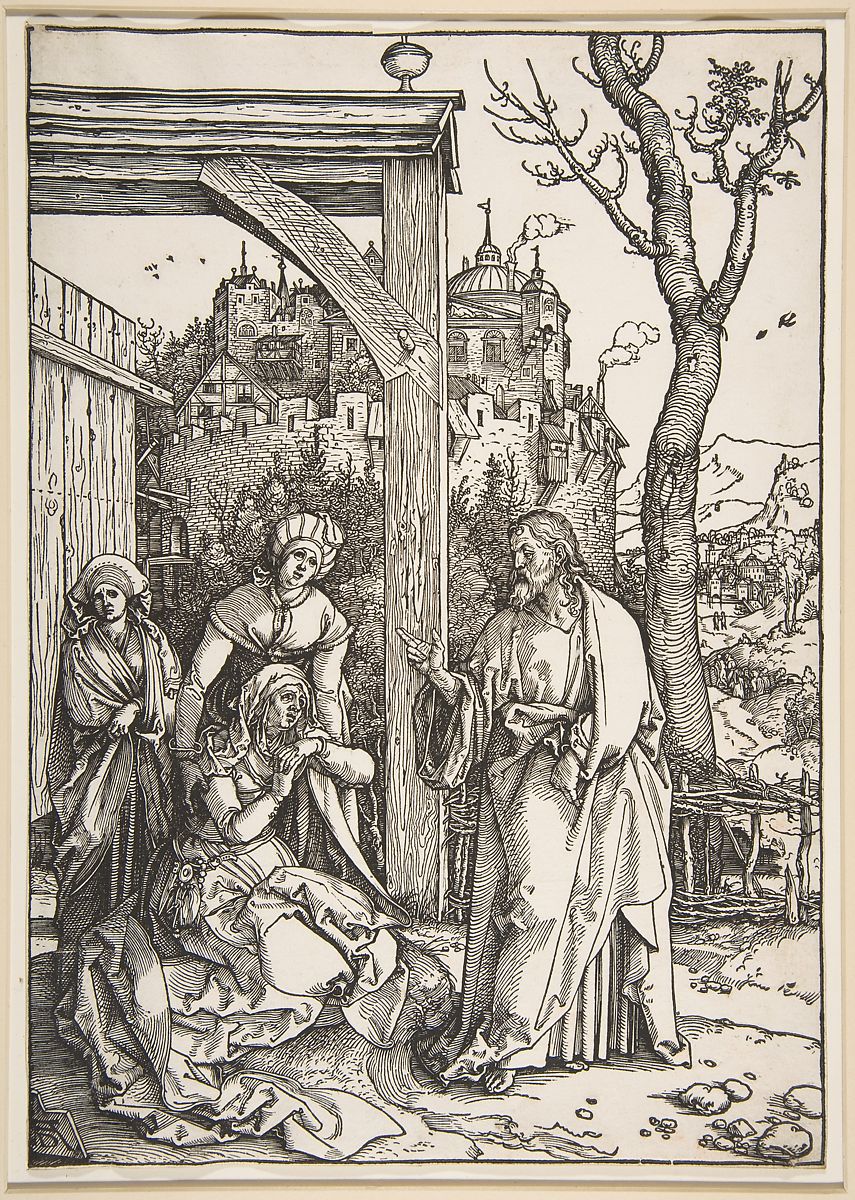

The impetus for this directive occurred several years prior. An earlier version of The Life of the Virgin was published in 1502, and, in 1506, a concerned friend of Dürer’s sent him a print that appeared to belong to the series. After examining it and determining it was a copy, Dürer brought a lawsuit against the creator, accomplished artist Marcantonio Raimondi (1480–1534). Art historian Noah Charney claims that this is the “first-known case of art-specific intellectual property law brought to trial.”6 Perhaps surprising to a modern audience, Raimondi was not found at fault. The Venetian court pronounced that although they were nearly identical and the exact same size, since he had made several small changes to the image, including adding his own signature and the mark of the publishing house (though keeping Dürer’s easily recognizable monogram, in the lower left corners of the figures below), it was not a forgery.

Albrecht Dürer, Christ Taking Leave of His Mother, from The Life of the Virgin, ca. 1504. Woodcut, sheet: 11 3/4 x 8 1/4 in. (29.8 x 21 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1918. 18.65.12, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/387875

Marcantonio Raimondi, Christ Taking Leave of His Mother, from The Life of the Virgin, after Albrecht Dürer, c. 1506. Engraving. 292 x 211mm. Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Christchurch, New Zealand. Sir Joseph Kinsey bequest. 69/279, https://christchurchartgallery.org.nz/collection/69279/item/christ-taking-leave-of-his-mother-from-the-life-of.

Though there is no evidence that Raimondi used counterproofing here (in fact, many sources applaud him for his painstaking detail in copying Dürer’s prints by hand), it is easy to imagine that the technique might be useful in a situation such as this. Simply providing a rough outline to guide Raimondi’s reproduction would have saved him both time and labor, which would ultimately allow him to increase his print yield and sell more prints faster. When selling copies, production time could be crucial in selling as many prints as possible before the copying is discovered.

Raimondi was known for his penchant for replication. As Charney describes, “Raimondi was among the most famous and skillful printmakers of the sixteenth century. He was a major artist in his own right, but he was best known for having been Raphael’s official printmaker.”7 Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483–1520), known by the mononym Raphael, was an internationally known painter. Though the exact terms of Raimondi’s employment are unknown, Raphael supplied him with drawings that Raimondi would engrave and subsequently print.8 Printing at this time was a relatively inexpensive and new technology, and had the potential to reach much wider audiences than painting. As art historian Catherine Wilkinson writes, “Marcantonio’s prints came to be perceived as substitutes for Raphael’s paintings and were widely collected and used by such artists as Rembrandt or Delacroix, whose experience of original paintings by Raphael was limited.”9 Wilkinson also describes prints as similar to a modern day reference book, writing that “prints were ‘reproductions’ (a sort of sixteenth-century equivalent of photographs),” and that Raimondi’s prints provided artists “with a stock of available images, ready to use in their own works.”10

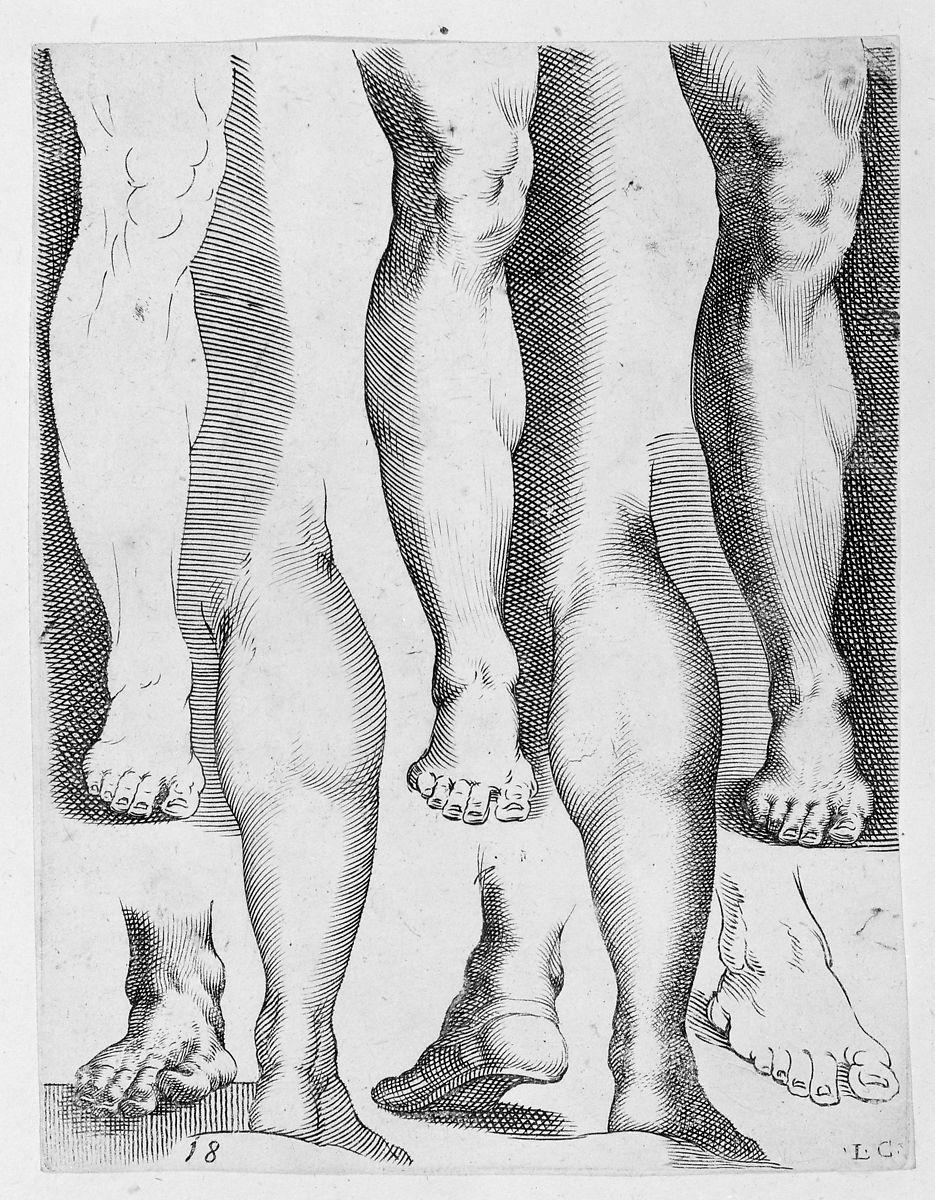

Art historian Hannah Friedman examines another motivation for copying: teaching. In her lecture “Modern Michelangelos? Copies, Fakes, and New Economies of Taste in the Early Seicento,” she describes a print of a study of legs by printer Luca Ciamberlano (1580–1641), done after a drawing by artist Agostino Carracci (1557–1602).11 This and similar prints were made as educational tools and often compiled in books.12 The purpose of these books, often referred to as “drawing books,” was to teach life drawing skills outside of the typical artist workshop environment.13 As Friedman indicates, images from certain artists, such as Michelangelo (1475–1564), were particularly valued as means of learning from great masters by copying them. Some such drawings could be successfully sold as forgeries.

Luca Ciamberlano, Five Legs and Three Feet, 17th century. Engraving, sheet: 6 1/16 x 4 11/16 in. (15.4 x 11.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1951. 51.501.270, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/386108.

This seemingly generous offering of technical knowledge may seem like an unexpected development in the lucrative art market. In art historian Christina Neilson’s essay “Demonstrating Ingenuity: The Display and Concealment of Knowledge in Renaissance Artists’ Workshops,” she investigates attitudes regarding knowledge sharing during this time. She writes,

In his treatise, Biringuccio explains why he is revealing the secret of using mercury to extract gold and silver from metal sweepings…: ‘in order that you [the reader] should esteem and value [this knowledge] so much more.’14 Biringuccio’s comment may be taken to stand for a general attitude toward the motivation of artisans in revealing knowledge during the Renaissance, manifested in the explosion of manuscripts and printed books on information about the so called mechanical arts: the value of revealing previously held secrets lay in the appreciation of that knowledge (and the appreciation of those who disseminated it) by patrons.15

Ms. Fr. 640 is one such text on technical knowledge; perhaps the theft technique is included merely to entice a reader, or to assert expertise. Neilson continues, “But to keep their patron–and other visitors–interested, artists often withheld information to add to the mystique of their work.”16 This oscillation between openness and secrecy, remaining irreplaceable to patrons while advertising to new audiences (or new patrons), coupled with emerging questions of authorship provides insights into why the author-practitioner may have seen value in secretly copying imagery. Perhaps he wanted to reproduce another’s work and sell it as his own, or innocently wanted to learn from another artist whose prints were in demand, possibly at the request of a patron. Inclusion of the method could have served as a means of flaunting his skill in order to promote himself to possible students, apprentices, other artisans, or customers. He may have wanted a copy of an image to use as a reference, such as Raimondi’s prints after Raphael. It could have even been a cost-saving solution to acquire new prints without paying for them.

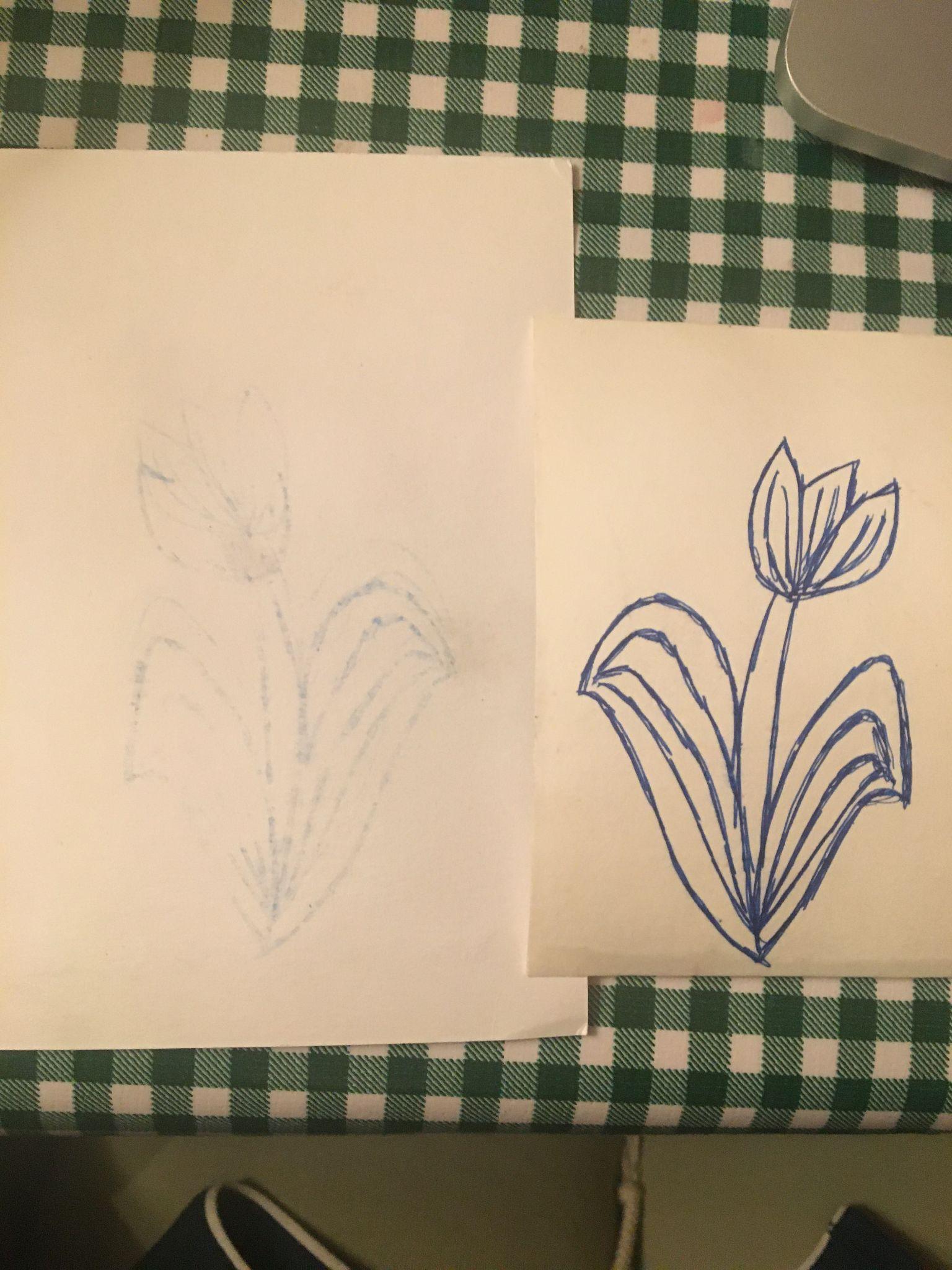

Though I did not have the exact materials that the author-practitioner most likely used, I tested the basic efficacy of this technique for removing evidence of counterproofing. I did not have a print suitable for this test, so I used an ink drawing that I did in pen. As can be seen in my field notes, the method worked surprisingly well.17 I successfully transferred the image to fresh paper, though I was not able to print it exactly or in perfect detail. For removing evidence of the process, I found that by following the author-practitioner’s instructions and dampening the original, nearly all burnishing marks were erased. Those remaining were hardly noticeable, even when closely searching for them. Whatever the author-practitioner may have done with his covert copies, it certainly seems he was capable of getting away with it.

Results of counterproofing test. On the left, the new print, and on the right, the original drawing used here.

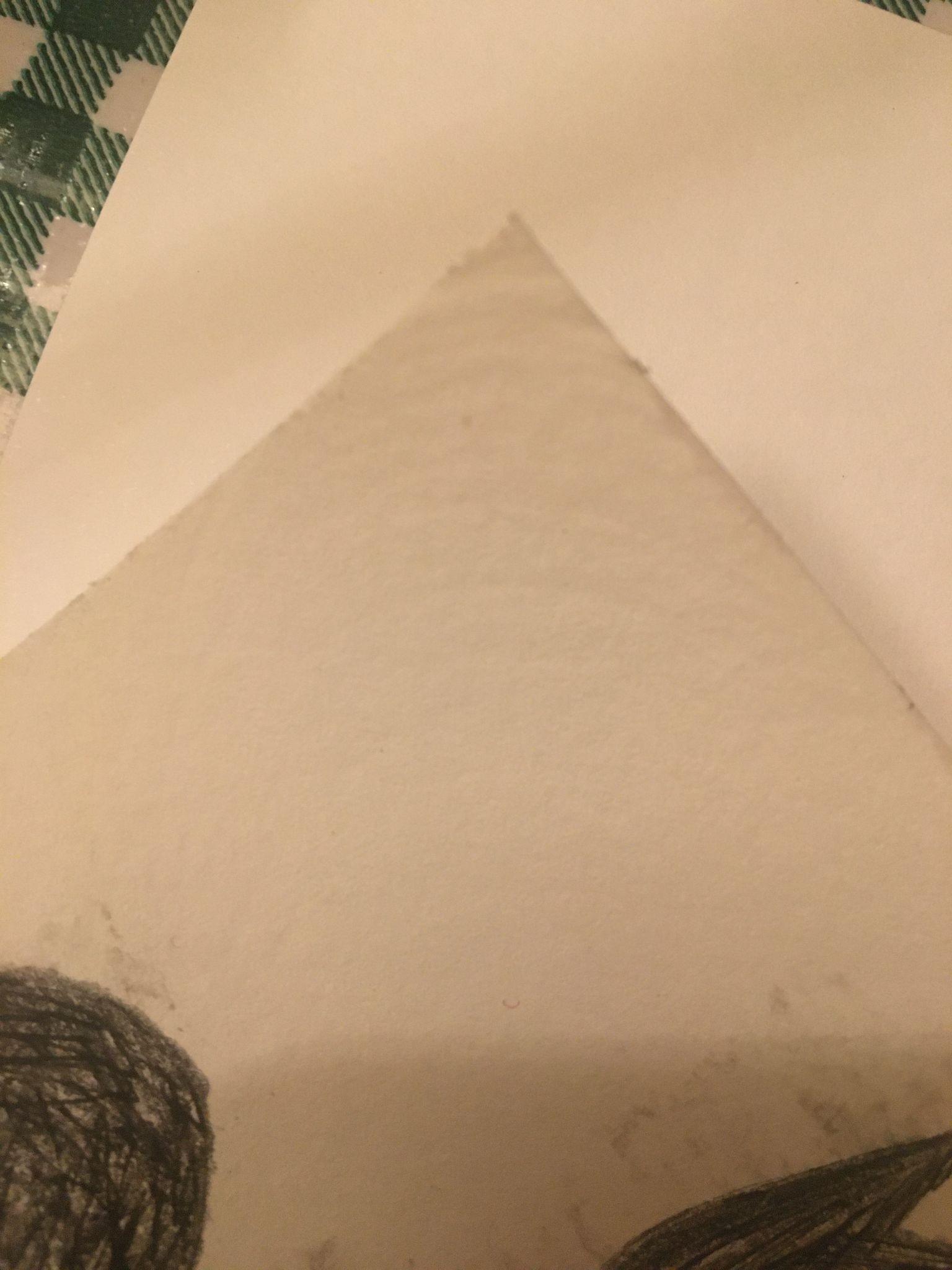

A corner of the back of the original drawing after burnishing, with the round indentations of the muller I used visible.

The same corner after wetting it and letting it dry. As is clear, the indentations are no longer visible.

Bibliography

Bertozzi, Nicole. “Transferring Images.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_067_fa_18. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/qmcq-ce66.

Charney, Noah. The Art of Forgery: The Minds, Motives and Methods of the Master Forgers. London: Phaidon Press Limited, 2015.

Charney, Noah. The Devil in the Gallery: How Scandal, Shock, and Rivalry Shaped the Art World. Blue Ridge Summit: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2021. Accessed May 13, 2022. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Ford, Lauren Moya. “How Europe Learned to Draw.” Hyperallergic. January 1, 2020. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://hyperallergic.com/526880/how-europe-learned-to-draw/.

Friedman, Hannah. “Modern Michelangelos? Copies, Fakes, and New Economies of Taste in the Early Seicento.” Paper presented at “When Michelangelo Was Modern: The Art Market and Collecting in Italy, 1450–1650,” organized by the Center for the History of Collecting, Frick Art Reference Library, New York. April 13, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VuB9EtQ8DeY.

Hosington, Brenda M. “Introduction: Translation and Print Culture in Early Modern Europe.” Renaissance Studies 29, no. 1 (2015): 5–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26631746.

Long, Pamela O. Openness, Secrecy, Authorship: Technical Arts and the Culture of Knowledge From Antiquity to the Renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 2001.

Neilson, Christina. “Demonstrating Ingenuity: The Display and Concealment of Knowledge in Renaissance Artists’ Workshops.” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance 19, no. 1 (2016): 63–91. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26558270.

Pon, Lisa. “Prints and Privileges: Regulating the Image in 16th-Century Italy.” Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin 6, no. 2 (1998): 40–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4301572.

Pyne, Lydia. “The Proliferation and Politics of Copies During the Renaissance.” Hyperallergic. April 29, 2019. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://hyperallergic.com/497448/copies-fakes-and-reproductions-printmaking-in-the-renaissance-blanton-museum-of-art/.

Solly, Meilan. “What Differentiates Renaissance Copies, Fakes and Reproductions?” Smithsonian Magazine, May 7, 2019. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/austin-exhibition-asks-what-differentiates-renaissance-copies-fakes-and-reproductions-180972094/.

Stijnman, Ad. “It’s All about Matter: Thoughts on Art History from the Perspective of the Maker.” Art in Print 6, no. 3 (2016): 16–17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26408682.

Stijnman, Ad. Engraving and Etching, 1400–2000: A History of the Development of Manual Intaglio Printmaking. London: Archetype Publications, 2012.

Wilkinson, Catherine. “The Engravings of Marcantonio Raimondi.” Art Journal 42, no. 3 (1982): 236–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/776586.

Ad Stijnman, Engraving and Etching, 1400–2000: A History of the Development of Manual Intaglio Printmaking (London: Archetype Publications, 2012), p. 159. ↩︎

Nicole Bertozzi, “Transferring Images,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020). https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_067_fa_18. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/qmcq-ce66. ↩︎

Brenda M. Hosington, “Introduction: Translation and Print Culture in Early Modern Europe,” Renaissance Studies 29, no. 1 (2015): 5–18. p.7. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26631746. ↩︎

Lisa Pon, “Prints and Privileges: Regulating the Image in 16th-Century Italy,” Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin 6, no. 2 (1998): 40–64. p. 41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4301572. ↩︎

Quoted by Pon, quoting Joseph Koerner’s translation from The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art (Chicago, 1993), p. 213. ↩︎

Noah Charney, The Art of Forgery: The Minds, Motives and Methods of the Master Forgers (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 2015), p. 12. ↩︎

Noah Charney, The Devil in the Gallery: How Scandal, Shock, and Rivalry Shaped the Art World (Blue Ridge Summit: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2021), p. 84. Accessed May 13, 2022. ProQuest Ebook Central. ↩︎

Catherine Wilkinson, “The Engravings of Marcantonio Raimondi,” Art Journal 42, no. 3 (1982): 236–39. p. 237. https://doi.org/10.2307/776586. ↩︎

Ibid. p. 239. ↩︎

Ibid. p. 238. ↩︎

Hannah Friedman, “Modern Michelangelos? Copies, Fakes, and New Economies of Taste in the Early Seicento.” Paper presented at “When Michelangelo Was Modern: The Art Market and Collecting in Italy, 1450–1650” organized by the Center for the History of Collecting, Frick Art Reference Library, New York. April 13, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VuB9EtQ8DeY. ↩︎

For an excellent digital reproduction of one such book, see this link to one in the collection of the Biblioteca Nacional de España: http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=bdh0000251828. ↩︎

Lauren Moya Ford, “How Europe Learned to Draw,” Hyperallergic, January 1, 2020. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://hyperallergic.com/526880/how-europe-learned-to-draw/. ↩︎

Pamela O. Long, Openness, Secrecy, Authorship: Technical Arts and the Culture of Knowledge From Antiquity to the Renaissance. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001). https://www.press.jhu.edu/books/title/2083/openness-secrecy-authorship. ↩︎

Christina Neilson, “Demonstrating Ingenuity: The Display and Concealment of Knowledge in Renaissance Artists’ Workshops,” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance 19, no. 1 (2016): 63–91. p. 78 https://www.jstor.org/stable/26558270. ↩︎

Ibid. p. 78. ↩︎

Linked here: sp22_lang_theodora_final_counterproofing ↩︎