Intertextuality and the Anonymous Author-Practitioner of Ms. Fr. 640

Javier R. Ardila

Introduction

Ms. Fr. 640 is full of mystery. Over the last decade, the Making and Knowing project has provided valuable insights into the complexities of this volume. An interdisciplinary team has used historical reconstruction to explore the early modern debates surrounding natural science, philosophy, alchemy, medicine, arts, and crafts, all while following the recipes of an unknown author-practitioner.1 Despite the project’s substantial evidence indicating that this author was not just an educated scribe but also a practitioner of the recipes he documented, his identity remains a mystery. Additionally, the sources he relied on to create the volume and the purpose of his laborious endeavor are still unclear. Another enigma appears at both the beginning and the end of the codex: a list of authors and book titles.

The author-practitioner began a manuscript book with a list of titles and authors. A recipe of herbs and opioids to work against the plague. By the recipe, on the left margin, he wrote what seems to be a reference: Othonis episcopi Frisigensis ab orbe condito. This loose allusion points toward Otto Frisingensis (ca. 1114–1158), bishop of Freising and chronicler, and to his work Chronicon sive rerum ab orbe condito ad sua usque tempora gestarum [Chronicon, or of the Events of The World from The Creation Until Its Current Times] (Ms640.R70D).2 Right after, the author wrote a new formula, this time one “to preserve oneself when one goes into infected air.” The recipe of vinegar, rue, and juniper berries stands beside two references: Abbatis Urspergensis Chronicon [Konrad of Lichtenau (d. 1240), Chronicum Abbatis Urspergensis: a Nino Rege Assyriorum Magno usque Fridericum II] (Ms640.R71D) and “Hyeronimus / Mercurialis / Variarum” [Girolamo Mercuriale (1530-1606), Variarum lectionum, in medicinae scriptoribus & aliis, libri sex (1585)] (Ms640.R72D). Immediately after, the writer listed six entries of authors and titles. For an unknown reason, the author seemed to have decided to turn the book upside down and start working from the back of the blank book. The list of references continues with another sixty titles at the back (now front) of the book.3

The list has provoked several possible interpretations, from the representation of a possible physical collection of books to an ideal list of references. Still, this document section has not yet been analyzed in depth. Following Andrew Hui’s very provocative invitation: “A history of Renaissance knowledge — or, for that matter, any knowledge — without a consideration of the study would be incomplete. We should study personal libraries because they are the sites of our knowledge production — and sometimes destruction. To study the study, then, is to take a critical gaze at our own day-to-day practice of scholarly work. A historical investigation into the personal library would very much inform our present habits of mind.”4

This paper examines a list of eighty references included in the manuscript. My central argument is that, despite various uncertainties regarding the meaning or authorship of this list, it provides insight into the cultural and intellectual landscapes of the sixteenth century. Compiling authors and titles is not merely an intellectual exercise in organizing scattered elements but also reflects processes of inclusion and exclusion within a semantic field.5 The list is a piece of evidence about the debates surrounding the production of the manuscript Ms. Fr. 640. If the numerous recipes of crafts collected by the author-practitioner show a world where practical knowledge is crucial for interpreting the external, inner, and social worlds, the list of titles is also a window that pushes out of the manuscript and the workshop. Following Chartier’s description of the centripetal and centrifugal forces in a library, reading, in general, can lead to a process of joining and union with a broader context, as well as one for rupture and seclusion.6 The interplay between reception and appropriation leads to the idea that the list of authors and titles serves as both pieces of a puzzle and a bridge to the intellectual environment in which Ms. Fr. 640 was created. It also connects to simultaneous bibliographical debates.

This essay serves a descriptive purpose rather than an argumentative one. As previously noted, the connection between the list (presumably of books) and the rest of the manuscript remains unclear. While a potential disconnect may remind us of the limits of interpretation and caution us against drawing straightforward connections between ideas, books, and practical knowledge, this should not impede our analysis of the list itself. The primary aim of this paper is to identify the elements that make up the list and to explore what they reveal about the circulating titles and authors of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

My description is as detailed as the available evidence allows. Due to the limited data and supplementary sources, the reconstruction of the list has several gaps that will remain unfilled until more evidence is obtained. Despite these challenges, this research has identified the authors and compiled a possible list of eighty titles.7 With this information, I was able to trace the biographical and bibliographical recognition of each entry on the list. In a few cases, the research succeeded in making strong attributions regarding specific editions. However, a comprehensive description of the list through the lens of material texts has not been fully realized and is still necessary.8 The information regarding this aspect was very limited and mostly derived from the perspective of only a few titles. We can only begin to form hypotheses about the list’s epistemological aspects after gathering the essential elements needed to understand its contents and the profiles of the listed elements. For now, I aim to clarify the thematic contents of the texts listed, examine the balance between Ancient and Modern authors, and explore the geographical concentration with an eye toward vernacularization and nationalization.

This paper builds on over a decade of work from a diverse team of experts. I am deeply grateful to Professor Pamela Smith for sharing the information the team has gathered about the Collection Béthune with me and for providing insightful commentary on this intriguing list. Additionally, I relied largely on the transcriptions and identifications made by the team, which were published in the digital edition of the manuscript.9 Despite some minor discrepancies in the attribution of titles, I rely on the trustworthiness and accuracy of this outstanding transcription and translation work.10

I will begin with the premise that it is essential to describe the contents of the list before making any claims about its significance within Ms. Fr. 640. There is much invisible and unidentified information in this list of books, however, a more comprehensive understanding of the list is needed before establishing possible connections between it and the rest of the document.

Four Lists of Titles.

In his influential work, Jack Goody analyzed the impact of writing on cognitive practices. His goal was to examine how literacy affects intellect, particularly the process of reducing speech to graphic form. Drawing on evidence collected by European anthropologists from various regions worldwide (including Ghana, Sumer, Mesopotamia, and Egypt), Goody demonstrated that written language caused a fundamental transformation through the decontextualization of knowledge. This process involves separating utterances — which are ephemeral — from their specific contexts. Goody emphasized that writing practices significantly enhance our ability to view words as archival resources and tools for cognitive operations and intellectual techniques. The meaning of written words can vary, and scriptural practices often lead to contradictions, ambiguities, and ambivalences that depend on the context.11 Goody emphasizes that lists allow the reorganization of knowledge beyond the constraints of oral traditions. Written practices enable a distinct relationship with knowledge storage characterized by the flexibility of free arrangement, unlike the rigid methods found in oral societies. As a result, writing practices significantly influence knowledge organization by allowing permanent discontinuity.12

Following Goody’s analysis, the list in Ms. Fr. 640 exhibits both discontinuity and connections among objects within a semantic field. While there is still uncertainty regarding the exact nature of this list, previous and current research on the manuscript’s contents suggests that it includes several homogeneous variables. Firstly, there is a name attributed to an author. As Chartier points out, the authorship of a book can involve multiple entities beyond just the writer. In the early modern period, authorship might encompass not only the attributed author but also translators, commentators, abridgers, patrons, booksellers, and others involved in circulating a title and producing a book.13 Secondly, some items in the list include the title of a work. In many cases, the titles are very specific, but there are instances where the scribe takes a less rigorous approach, using just keywords or descriptive adjectives. Additionally, there are rare occasions when the information provided includes the printer’s name, and only one entry specifies the city and year of publication. Considering these elements, it can be concluded that the list in Ms. Fr. 640 primarily serves as a compilation of authors rather than a catalog of titles and, even more distantly, a list of books.

Information about authors, titles, and books is dispersed throughout the manuscript. However, it can be gathered into four main sections. For this analysis, I have categorized each section into a distinct list. The format and content of each list differ from each other, indicating that they serve different purposes. This variation is also reflected in the individual entry’s appearance and the list’s overall contents and forms.

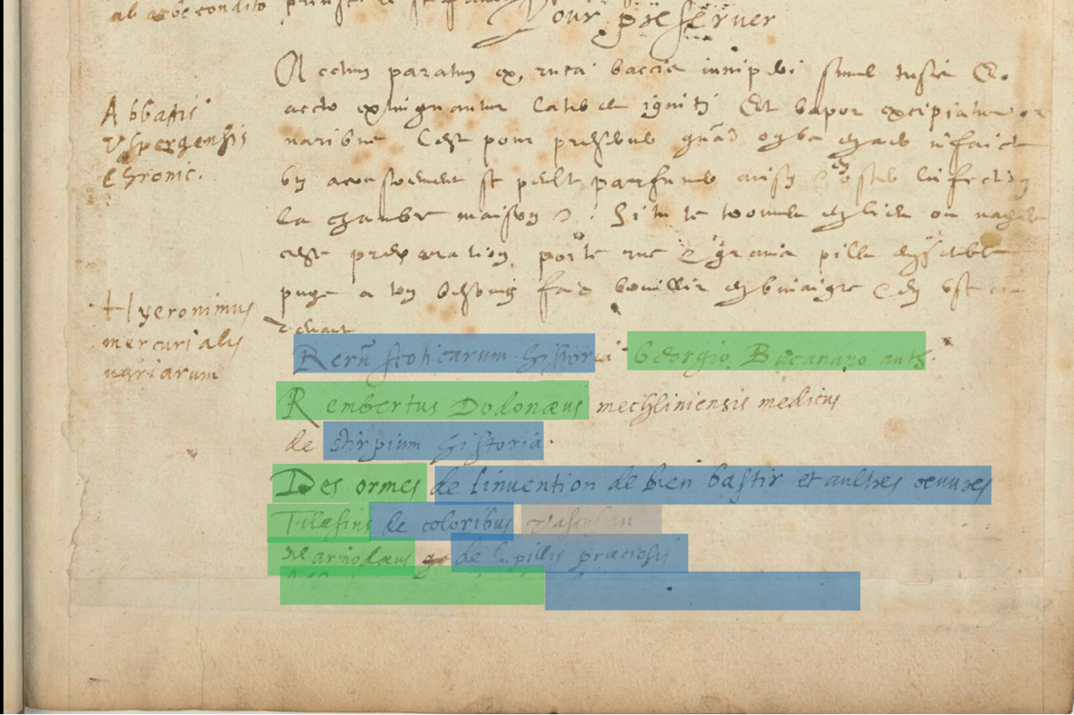

Fig. 1. Ms. Fr. 640 – Fol. 170v [Fragment]

List A

Source: Making and Knowing Project. Digital Critical Edition, fol. 170v. Digital highlight by the author: title (blue), author (green), printer (grey).

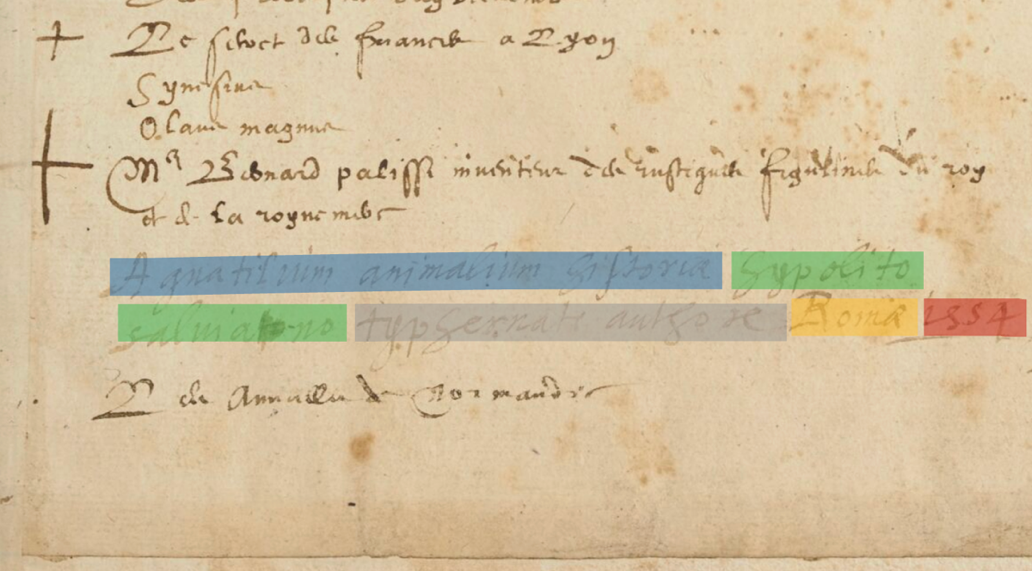

Fig. 2. Ms. Fr. 640 – Fol. 1r [Fragment]

List A

Source: Making and Knowing Project. Digital Critical Edition, fol. 170v. Digital highlight by the author: title (blue), author (green), printer (grey), city (yellow), year (red).

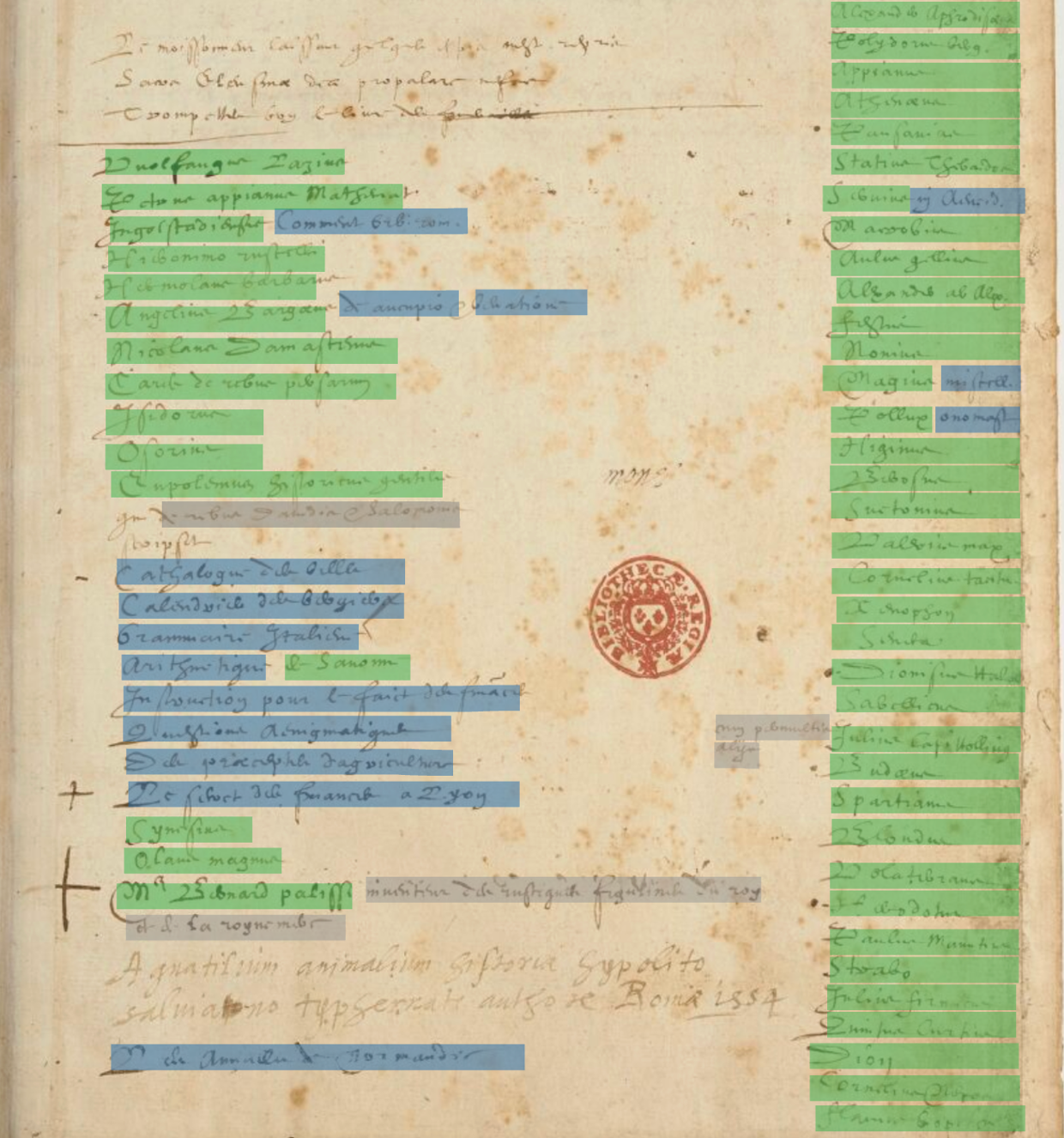

List A starts on the last page and is identified as the first part of the list of books. It is arranged opposite the order and layout of the manuscript’s final folio.14 One entry from the same list continues onto the first page (fol. 1r), following the standard format of the entire volume. It is noticeable that the handwriting in this list is similar, differing from the other three lists. When combining the titles from List A found on fols. 170v and 1r, we arrive at a total of seven entries. This list seems to be the most comprehensive in terms of pairing information about the titles with their respective authors. All seven entries include details about both the author and the title. Two of them also provide information about the printer, and one includes the city and year of printing. The similarities extend beyond format; the contents also reflect thematic connections, with the titles mainly associated with Natural Philosophy and Arts and Secrets. As indicated, the elements of List A extend into fol. 1r, where List B is also present. However, despite the overlap between the registers, the entries from List A maintain a distinct form, format, and content, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

List B appears on the first page of the manuscript (fol. 1r). As shown in Fig. 2, it was written in a different handwriting than List A. It is unclear whether the same scribe used two styles or if the lists were intended for two individuals. Comprising 59 entries, List B is the longest compilation of authors and titles within Ms. Fr. 640. The list is arranged in two columns, with each entry typically containing only the author’s name or title and occasionally some combined information (as seen in Fig. 3). Many authors are classical writers, each associated with only a recognizable title. In seven instances, it was not possible to identify the title at all. Overall, making any claims about the edition of the items is quite challenging due to the limited information available for attribution.

The entry to the Jewish historian Eupolemus (Second century BCE) (Ms640.R11B) provides insights regarding the nature of the inventory. The author-practitioner included a commentary that refers to Eupolemus as “historicus gentilis qui de rebus Davidis & Salomonis scripsit,” indicating that he was a pagan historian who wrote the history of David and Solomon. The team from Making and Knowing identified that this commentary was likely sourced from Josuae Imperatoris Historia Illustrata by Andreas Masius (1514–1573), who describes Eupolemus in very similar terms in his index.15 This case strengthens the possibility that List B represents an ideal recollection of references.

Fig. 3. Ms. Fr. 640 – Fol. 1r [Fragment]

List B

Source: Making and Knowing Project. Digital Critical Edition, fol. 170v. Digital highlight by the author: title (blue), author (green), commentaries (grey).

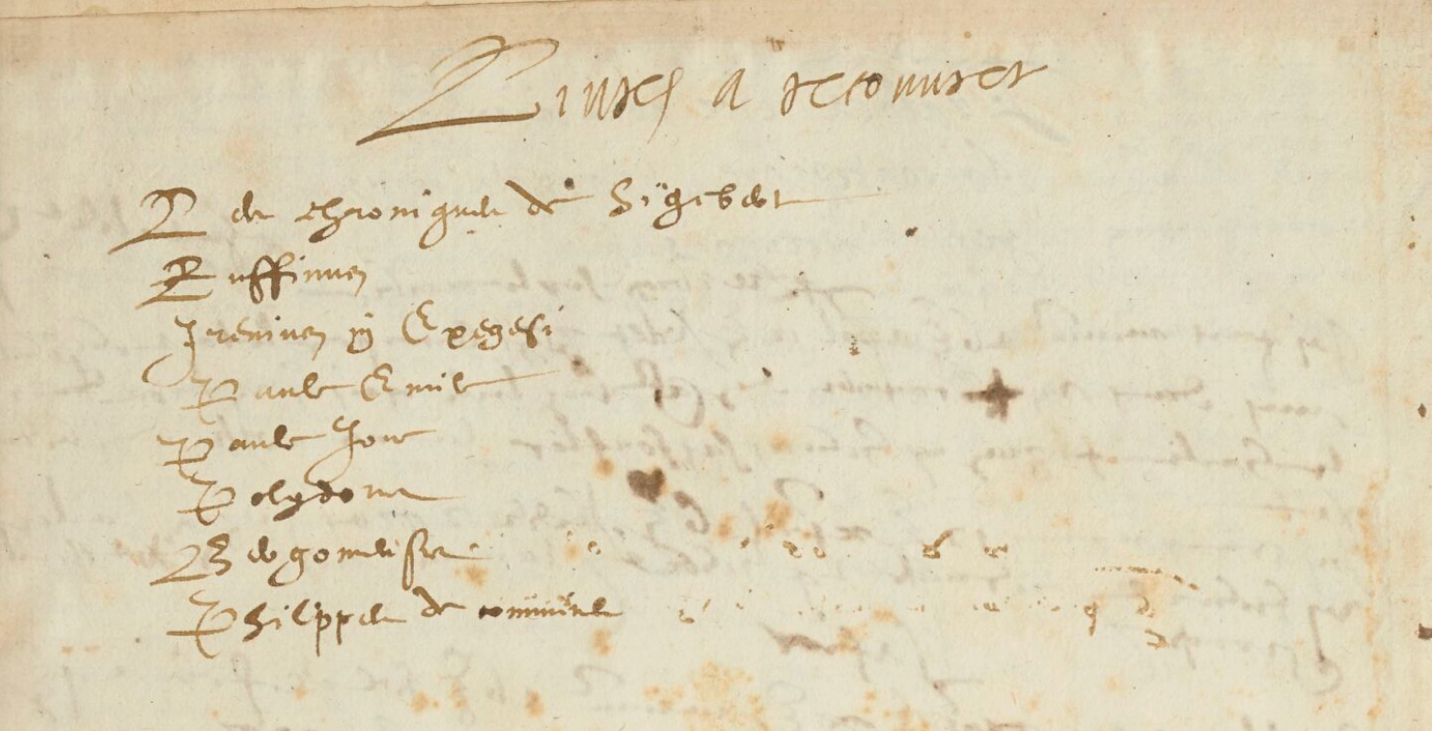

List C introduces additional complexity. It appears in the “Livres a recouvrer” [Books to recover] entry on fol. 2r. The handwriting and format are similar to those found in List B. Although there are eight entries, only two provide information about the titles, and one of them remains unidentified (Ms640.R66C). Furthermore, there is a repetition with List B, as both lists include a reference to Polydor Vergil (Ms640.R26B, Ms640.R67C). The presence of this title and the repeated authors suggest that at least some elements of the lists were indeed physical books that the author or practitioner accessed, either as a borrower or an owner.

List D compiles the references found throughout the manuscript. Although most are located on the last page (fol. 170v), this list includes three entries from different manuscript sections. The first entry is on fol. 1r, at the beginning of the first column, which mentions a book on funerary practices along with a saying: “Trompettes voy le livre des funerailles” (Ms640.R61D). The second entry, found on fol. 35v, discusses a method for preventing someone from eating a certain food. The author-practitioner references Matthiolus (Ms640.R80D), who suggests adding arum, a plant known to be poisonous, to the food, assuring that “il ny a poinct de dangier Voy Mathiol” [there is no danger in this. See Mathiol]. Finally, on fol. 53v, there is a reference to a discussion about silkworms. The author cites Girolamo Vida of Cremona’s “Bucolica de Bombyce,” a book dedicated to this topic (Ms640.R69D).

To sum up, this research suggests that the entries for books and authors should be categorized into four distinct lists. Each list has unique characteristics in terms of form, format, and content. These variations may be related not only to the author-practitioner’s physical access to the texts but also to their intended uses and purposes. Lists A and D appear to be most aligned with the actual practices of reading and appropriation. List A offers a more detailed description of the titles, while List D is more connected to the narratives of the recipes and the use of elements from other titles, which enhance particular contents in the manuscript or link them to broader discussions. Although brief, List C suggests that the collection includes at least one element of physicality. The references to “books to recover” and the repetition of items across different sections within the lists indicate possible overlaps between ideal and material objects in the manuscript. Lastly, List B, being the longest, presents significant challenges. The information provided does not allow for a definitive conclusion regarding whether the author listed authors, titles, or books. Nonetheless, its extensive nature invites a deeper analysis of its contents.

Fig. 4. Ms. Fr. 640 – Fol. 2r [Fragment]

List C

Source: Making and Knowing Project. Digital Critical Edition, fol. 170v. Digital highlight by the author: title (blue), author (green),

Contents of the list

After characterizing and distinguishing how the author-practitioner presented bibliographical information in the manuscript, this section provides an overview of the general contents of these records. The lists have no apparent classification system, as the scribe did not include any subject headings. Nevertheless, a close analysis reveals some similarities between neighboring entries. To explore the thematic nature of the list, this investigation compared three circulating classification systems during the Renaissance, though there is no certainty that the author-practitioner was directly aware of or applied them. However, two of these three systems appeared in authors included in the lists found in Ms. Fr. 640, which increases the suitability and relevance of this attribution.

The Etymologiae (625 CE) by Isidore of Seville (Ms640.R9B) is a well-known title and may have been included in the author’s list, although there is no substantial evidence to confirm this attribution. Isidore’s work consists of twenty books, which can be organized into the following sections:

Trivium (Grammar, Rhetoric, Logic),

Quadrivium (Arithmetic, Astronomy, Music, Geometry),

Philosophy (Poets, Sybils, Sorcerers, Pagans)

Medicine

Jurisprudence (laws and customs, law, crimes, punishments, Time)

Theology (God, Patriarchs; Clergy; Monks, Church and Synagogue, Religion and Belief, Heresies and Schisms)

Physics (Languages and Peoples, Man and Parts of His Body, Animals, World, Earth, States, buildings, Sands, types of soil, products of the earth and water, stones)

Mechanical and Fine Arts (Agriculture, Wars, Plastic, sculpture Painting, colors Clothing, jewelry, equipment)

Isidore drew from the Classical Roman tradition, especially the works of Pliny the Elder. Etymologiae became highly popular and greatly influenced knowledge organization in the encyclopedic writings of the medieval and early Modern centuries. Additionally, Etymologiae witnessed continued popularity during the Renaissance, as evidenced by the many printed editions released and its inclusion in various lists of the author-practitioner’s.16

In Commentariorum rerum urbanorum (1506), Raffaele Maffei (Ms640.R3B), professor of law in Rome and with close relations with the Papal See, also offered a system of classification. In his work about Roman culture, he arranged the knowledge thus:

Geography and history (General geography, geography of antiquity, explanation of the celestial zones; countries of the world; geographical descriptions, the peoples living in individual countries and their history)

Anthropology (Famous people of all times, languages, and genders, from the ancient world and the Middle Ages; Chronological list of emperors, popes, scholars, etc.)

Philology [Various sciences and arts]

Zoology

Science of man [Medicine]

Science of animals

Botany and agriculture

Mineralogy; architecture; various skills and crafts

Social Sciences

Ethics

Law

Politics

Philological Sciences

Mathematical Sciences

Miscellaneous (“Paralipomena”)

During the Humanistic movement, it is fascinating to observe how authors like Maffei expanded the scope of grammar to encompass the study of all “realities.” Despite the mixed nature of the materials grouped together, Maffei’s organization of knowledge about natural materials reflects a continuation of Isidore’s influence and shows his indebtedness to Pliny’s Historia Naturalis.17

Thirdly, Conrad Gesner (1516-1565), in his Bibliotheca Universalis (1545), presented a crucial work to understand bibliography and knowledge classification in the early modern period.18 Although this is an author not listed within Ms. Fr. 640, Gesner’s effort to bring together authors in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew will become the model of future catalogs of ideal and universal libraries.19 He will classify the catalog as follows:

Trivium (Grammar, Dialectics, Rhetoric)

Quadrivium (Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, Astronomy)

Astrology and Magic

Geography

History

Arts, mechanical and others, (architecture, houses, craft skills, tools and work; on the processing of gold and silver; on the types of glass and mirrors; … on sculpture, household goods, riding, shipping, clothing, alchemy or chemistry, painting; food, arts and ways of life; first of commerce, then of the trade in medicines, agriculture)

Natural philosophy (Heavens and the universe, four elements, courses of time, of the four seasons, of the days and nights, of meteors, stones, metals, plants and animals, metals and similar substances called minerals, of plants, the soul, especially of the various sensations and properties, parva naturalia, [sleep and wakefulness, memory and ability to remember, life and death, youth and old age, breathing, ages], animals, natural magic and miracles

First philosophy (metaphysics, philosophy and of the philosophers of antiquity, theology)

Moral Philosophy

Economic philosophy

Civil philosophy (Politics, war)

Civil and canon law

Medicine

Christian Theology

Gesner’s closer connection to university teaching and the practical application of knowledge is noted as a compelling reason why his classifications exhibit a more specialized focus for each discipline compared to earlier systems.20

The three systems of classifications (Isidore, Maffei, and Gesner) follow the triad Liberal Arts (trivium and quadrivium), Mechanical Arts, and Philosophy.21 Although there is a variation and strong emphasis on the disciplinary and philosophical divisions among different branches of knowledge, synthesizing the three methods could help us better understand the thematic contents of the title lists in Ms. Fr. 640. Therefore, for the purposes of this paper, I have applied the following classification to the titles:

Trivium (Grammar, Dialectics, Rhetoric)

Quadrivium (Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, Astronomy)

Geography

History

Mechanical and fine arts

Poetry

Natural Philosophy

Human Philosophy

Medicine

N/A

Theology

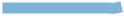

The distribution of themes reveals some notable discrepancies among the categories. For instance, within the Trivium, only Grammar is represented in the list, while from the Quadrivium, only Arithmetic and Astronomy are included. Additionally, a category labeled “Non-Applicable” (N/A) contains items with insufficient information about the title or author that prevents reasonable attribution. A visual summary of the thematic divisions can be found in Fig. 5.

The general trend indicates that most texts fall into the history category, which includes 36 out of 80 records. This group encompasses various types of writings, such as chronicles, biographies, archaeological descriptions, and accounts of political and military events. Notable titles in Universal history include Nicolaus of Damascus’s Universali Historia seu de Moribus Gentium (Ms640.R7B), Orosius’ Historiae Adversus Paganos (Ms640.R10B), Sigebert de Gembloux’s Chronicon (Ms640.R62C), Giacomo Filippo Foresti’s Supplementum Chronicarum (Ms640.R68C), and Otto of Freising’s Chronicon sive Rerum ab Orbe Condito (Ms640.R70D).

Fig. 5. Ms. Fr. 640 – Lists of References

Thematic Division

Created by Javier Ardila based on Making and Knowing Project, Secrets of Craft and Nature, fols. 1r, 2r, 35r, 53r, 170v.

There are also many significant authors from Greek and Roman antiquity. Among the prominent historians from the early millennia are Appian of Alexandria (Ms640.R27B), Suetonius (Ms640.R41B), Valerius Maximus (Ms640.R42B), Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Ms640.R46B), Quintus Curtius (Ms640.R57B), Cassius Dio (Ms640.R58B), and Cornelius Nepos (Ms640.R59B). The list also features canonical historians such as Xenophon (Ms640.R44B) and Herodotus (Ms640.R53B). Additionally, three enigmatic contributors to the Scriptores Historiae Augoustae — Julius Capitolinus (Ms640.R48B), Aelius Spartianus (Ms640.R50B), and Flavius Vopiscus (Ms640.R60B) — are listed.22 There were also historians from the Renaissance, such as Raffaello Maffei (Ms640.R3B), Paolo Manuzio (Ms640.R54B), and Favio Biondo (Ms640.R51B), the latter reputed for its distinction between the Ancient, Medieval, and Modern ages.23 The lists also include authors from Late Antiquity, such as Procopius Caesariensis his De Rebus Gothorum, Persarum Ac Vandalorum (Ms640.R8B); Orosius and the criticism to the pagans (Ms640.R10B), and the forgery of Berosus about Babylonian Antiquity (Ms640.R40B).

The history segment also includes several titles related to the formation of early modern nationalities. Olaus Magnus’ Historiae de Gentibus Septentrionalibus contributes to the narrative of the Nordic peoples, particularly focusing on Sweden (Ms640.R21B). Works by Nagarel (Ms640.R24B), Sabellicus (Ms640.R47B), Lichtenau (Ms640.R71D), and Buchanan (Ms640.R71A) appropriately address Normandy, Venice, Bavaria, and Scotland, respectively. Additionally, Paolo Emili wrote the history of France under the commission of the King of France (Ms640.R65C), while Philippe de Commines recorded his memories as a chronicle of his time (Ms640.R69C).

This list of historiography titles also includes some biographies of inventors, as, for example, the references to Polydorus Vergil his De Inventoribus Rerum (Ms640.R26B). Similarly, Guillaume Budé (1467-1540) also wrote a history of material antiquities (Ms640.R49B). Despite the concentration on history, the author-practitioner might have enlisted or approached them with a different purpose in mind, as the titles could be different from a book’s primary subject matter. For example, the reference to Conrad of Lichtenau was used to validate an argument about a remedy to fight the plague.

The second category of quantitative importance is mechanical and fine arts, which gathers 11 of the 80 records. This category includes not only books on secrets, possibly included with Ruscelli (Ms640.R4B), but also elements of practical agriculture (Ms640.R18B), calendars (Ms640.R13B), and time in the countryside. Following the Gesner tradition of classification, this section also should include titles on oeconomia such as Froumenteau’s [possibly Jean Frotte] Secrets de finances (LB.19) or Philibert Boyer’s Instruction pour le faict des fina[n]ces (Ms640.R19B).24 Questions aenigmatiques, by Du Verdier (Ms640.R17B), shows how the category also includes entertainments, amusements, and the use of time. Finally, the crafts include Palissy’s Discours admirables (Ms640.R22B), Guichard’s Funérailles et Diverses Manieres d’ensevelir (Ms640.R61D), Tilesius Libellus de Coloribus (Ms640.R76A), and de l’Orme’s Nouvelles Inventions (Ms640.R75A).

The section on Natural Philosophy includes six items. Among them are Ermolano Barbaro’s comments on Pliny (Ms640.R5B), Ippolito Salvini’s work on aquatic animals (Ms640.R23B), and Girolamo Vida’s description of silkworms (Ms640.R79D). Additionally, it contains Rembert Dodoens’ studies on botany (Ms640.R74A) and the works of Marbodus (Ms640.R77A) and Albertus Magnus on mineralogy (Ms640.R78A). In the Geography section, there are three titles: Cathalogue des villes by Gilles Corrozet (Ms640.R12B), Pausanias’ Graeciae Descriptio (Ms640.R29B), and Strabo’s Situ Orbis (Ms640.R55B). Lastly, the Medicine section includes references to Girolamo Mercuriale (Ms640.R72D) and Matthiolus (Ms640.R80D).

Poetry includes five closely related titles: Pietro degli Angeli’s poems about hunting with dogs and catching birds (Ms640.R6B); Athenaeus of Naucratis’s description of the Greek symposium (Ms640.R28B); Statius’s Thebaid (Ms640.R30B); Servius’s commentary on the Aeneid (Ms640.R31B); and Macrobius’s work on Scipione (Ms640.R32B).

Grammar, the sole discipline of the trivium represented in these lists, encompasses four titles: two concerning Latin grammar by Festus (Ms640.R35B) and Nonius Marcellus (Ms640.R36B), one in Greek by Julius Pollux (Ms640.R38B), and one in Italian by Mesmes (Ms640.R14B). The Italian grammar was the first to compare Italian and French, illustrating the shift towards vernacular language in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Similarly, the disciplines of the quadrivium also include four titles. In Arithmetic, we find works by Petrus Apianus (Ms640.R2B) and Savonne’s Arithmétique (Ms640.R15B). In Astronomy, the titles include Hyginus’s Poeticon Astronomicon (Ms640.R39B) and Julius Firmicus Maternus’ Astronomicon (Ms640.R56B).

Philosophy and Theology encompass four main titles. Philosophy includes the peripatetic Aphrodisias (Ms640.R25B), Aulus Gellius (Ms640.R33B), and Alessandro Alessandri (Ms640.R34B), all of whom collected and summarized the works of earlier thinkers. Theology includes only Irenaeus (Ms640.R64B).

As mentioned, five titles could not be identified due to the lack of specific information. The unidentified titles are Isidore of Seville, given the place, possibly was his Etymologiae (Ms640.R9B); Synesius (Ms640.R20B), who wrote extensively on politics, philosophy, and history; Cornelius Tacitus (Ms640.R43B), a renowned historian who was also a grammarian and orator. Seneca (Ms640.R45B), although the author-practitioner likely referred to Seneca the Younger, who wrote about philosophy and poetry. Finally, the humanist Paolo Giovio wrote several titles about topics ranging from natural philosophy to human history and chronicles (Ms640.R66C).

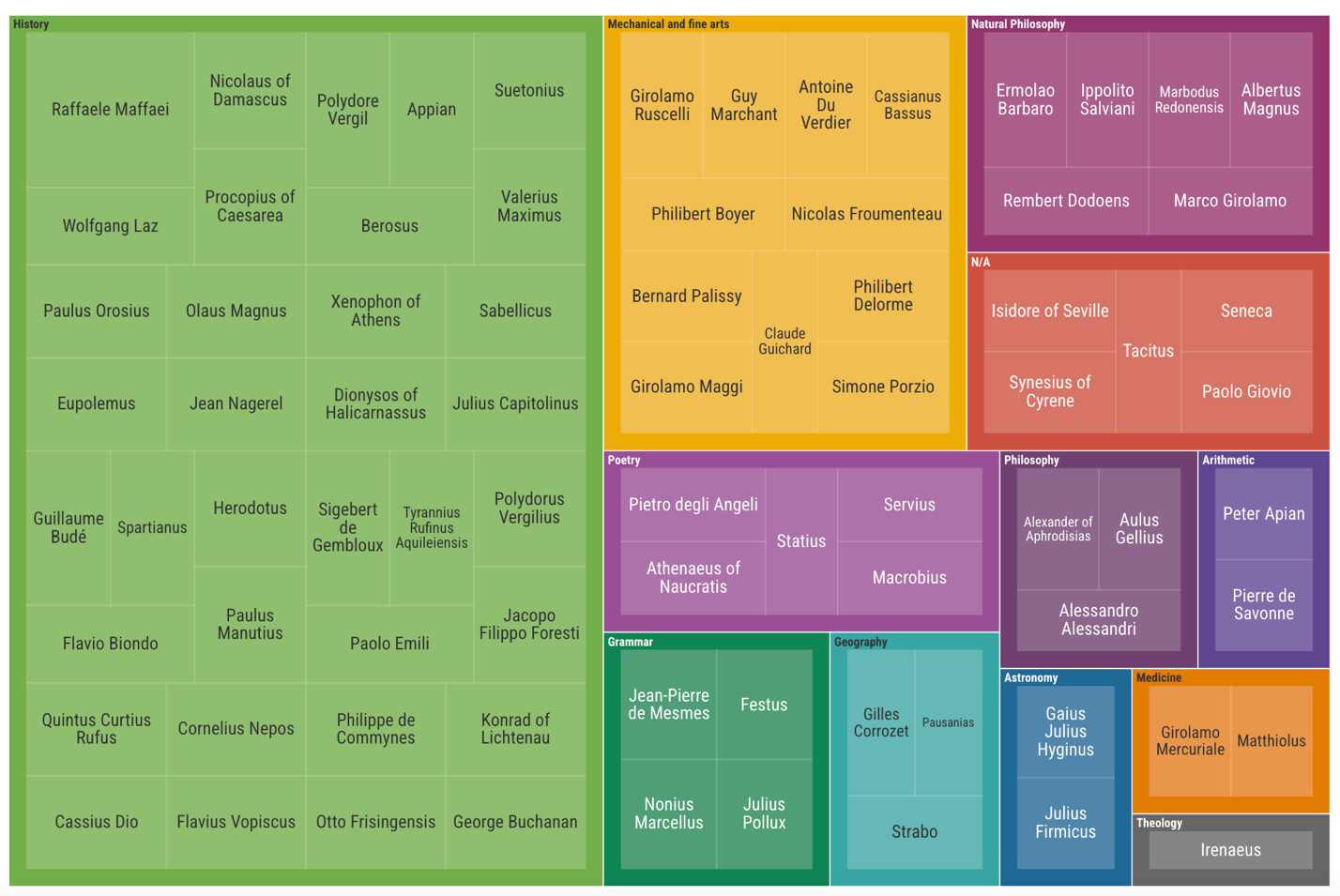

Fig. 6. Ms. Fr. 640 – Lists of References

Chronological Distribution (Authors)

Created by Javier Ardila based on Making and Knowing Project, Secrets of Craft and Nature, fols. 1r, 2r, 35r, 53r, 170v.

When analyzing the chronological distribution of authors, an interesting aspect of the lists emerges. These lists include titles ranging from Antiquity to the early modern period, with notable examples such as Herodotus (circa 484–circa 425 BCE) (Ms640.R53B) and Antoine Du Verdier (1544-1600) (Ms640.R17B). However, it is evident that most authors concentrate on the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Following Biondus’ division of history — one that the author-practitioner might have been familiar with (Ms640.R51B) — we can categorize the records into three periods: Antiquity, the Middle Ages, and Modernity. For the sake of this analysis, I will also include Late Antiquity and refer to the most recent period as Early Modernity (see Fig. 6).

In the Antiquity section, twenty-four titles span from the Fifth century BCE to the Second century CE. While there are some early Jewish historians included, such as Nicolaus of Damascus (Ms640.R7B), Eupolemus (Ms640.R11B) — both often compared to Flavius Josephus25 — and the Babylonian Berosus (Ms640.R40B), most entries focus on Roman and Greek authors.26 Among the Greek authors featured are Herodotus, Xenophon, and several from the first century, including Aphrodisias, Appianus, Athenaeus, Pausanias, Julius Pollux, Dionysius, Strabo, and Cassius Dio. On the Roman side, we find Statius, Gellius, Festus, Hyginus, Suetonius, Valerius Maximus, Tacitus, Seneca, Quintus Curtius, and Nepos. Interestingly, some of these authors are grouped closely together in the list (Ms640.R26B– Ms640.R30B, Ms640.R38B–Ms640.R46B). This arrangement suggests that the author or compiler may have found it convenient to cluster their names, possibly due to intellectual connections or practical considerations regarding the distribution of their works in a physical space.

Late Antiquity contains thirteen authors born between the third and eighth centuries. These authors include early Christians and Romans from both the Byzantine Empire and the West. The first group comprises Isidore of Seville, Orosius, Rufinus of Aquileia, and Irenaeus. The second group includes Procopius, Cassianus Bassus, Synesius, and Macrobius. Finally, the third group comprises Servius, Nonius, and the writers of the Historiae Augusta.

The Medieval section assembled limited numbers, with only five items produced between the ninth and thirteenth centuries. However, there is an interesting diversity in the geographical origins of the authors, primarily from Dutch, German, and Gallic traditions, all of whom were members of the Catholic Church. This section includes three chroniclers: Sigebert of Gembloux, Otto of Freising, and Conrad of Lichtenau, along with two natural philosophers, Marbodus and Albertus Magnus, the latter recognized as a Saint by the Catholic Church.

The Renaissance, marked by the emergence of studia humanitatis — a crucial element in the periodization of the early modern era — contains the majority of the items. Thirty-eight entries span the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, featuring prominent European authors recognized for their significant contributions to the humanist movement. Among them are Polydore Vergil, who was friends with Thomas More and Erasmus, as well as Guillaume Budé.27 In addition to these well-known figures, others held considerable influence among their contemporaries and continue to be studied by scholars today. Noteworthy individuals include Wolfgang Lazius, a physician and historian; Petrus Apianus, a mathematician and cosmographer who crafted his own instruments for cosmography and integrated them into his published works.28 Raffaele Maffei, a prominent figure in Rome, appears as part of this section of the list.29 Other significant figures include Pierre de Savonne, known for his expertise in accounting; Bernard Palissy, a renowned artisan and natural philosopher from Paris; and Flavio Biondo.

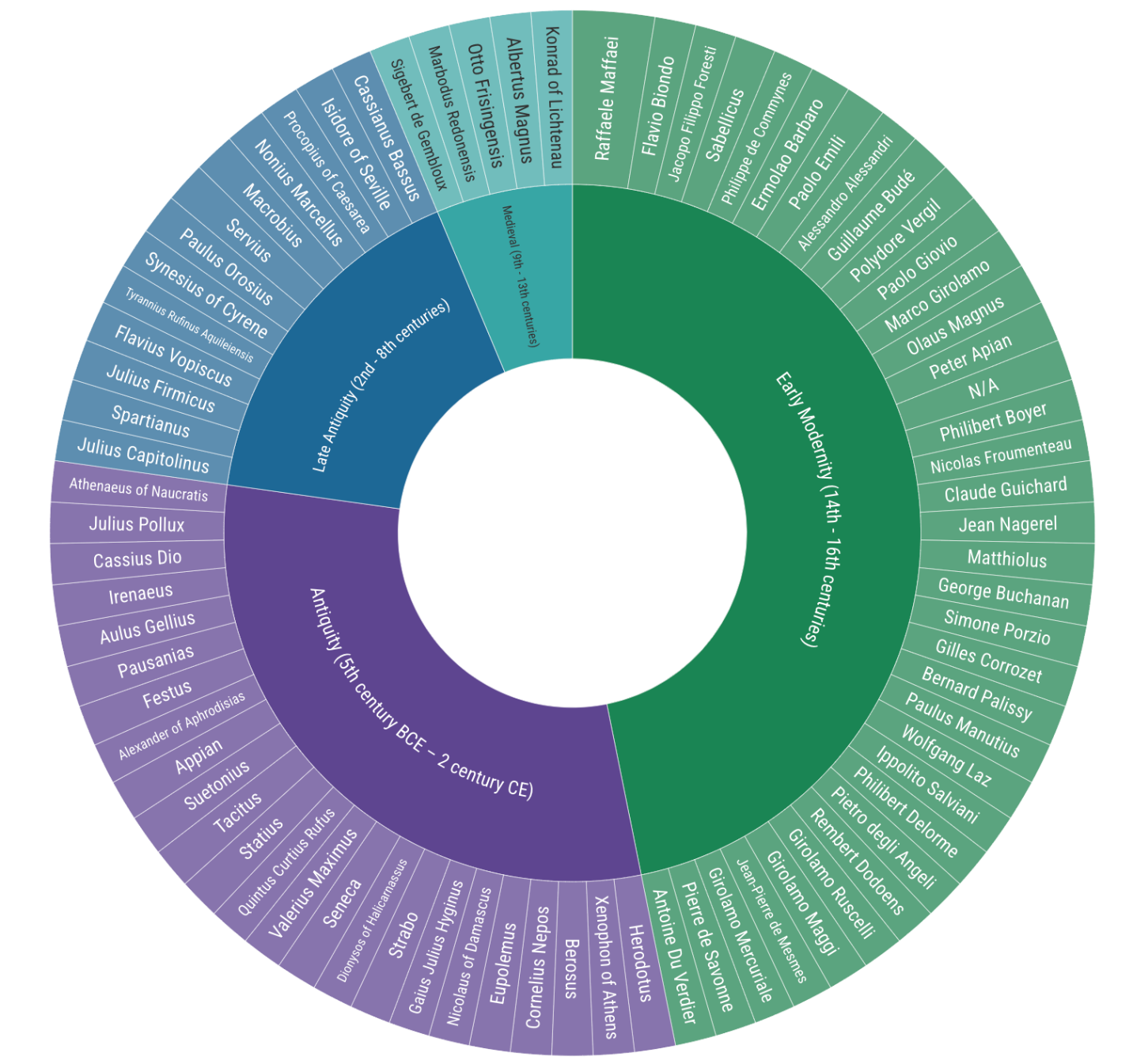

The historical division invites us to acknowledge the authors’ geographical origins, which are not confined to modern nation-states. I categorized the items into thirteen groups: Asia Minor, Austrian, British, Byzantine, Dutch, Gallic, Germanic, Greek, Iberian, Italian, Middle Eastern, Nordic, and North African. Overall, most authors were linked to Italy as a cultural center. However, a significant shift occurred during the Early Modern period, with an increase in items related to the Gallic region (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Ms. Fr. 640 – Lists of References

Geographic Concentration (Authors)

Created by Javier Ardila based on the Making and Knowing Project. Secrets of Craft and Nature, fols. 1r, 2r, 35r, 53r, 170v.

Considerations

The list of titles and authors in Ms. Fr. 640 should be examined in the context of Toulouse in the late sixteenth century.30 The introduction of printed materials in the mid-fifteenth century gave a new shape to European intellectual life.31 The proliferation of texts was the result of long-term transformations in the cultural and technological realms, such as the emergence and consolidation of universities since the twelfth century, the expansion of a scribal culture from the monasteries to secular scenarios, the introduction, and production of paper, the emergence of xylography and other forms of image reproduction.32 Still, the print of moveable type brought novel forms of information circulation in the European context.

If the printing press had its first development in the German countries and Italy, the French contexts soon implemented the new technology and began the systematic production of print culture materials.33 In terms of production, Paris and Lyons were crucial spaces for printing press production in the fifteenth century, though Venice preserved its overall primacy within the European context.34 The press appeared in Toulouse in 1477. Like most typographic practices in other places in France, the first printers in Toulouse had German origins, used Gothic types, and printed documents in Latin. Heinrich Turner and Johannes Parix were the first to establish print workshops in the city, with a significant production of legal documentation.35

If the studies of the libraries of lawyers and the elite show a generational time lag between the publication of a work and its introduction in French humanist libraries, the existence of at least twenty-five thousand impressions — that resulted in about twenty-five million copies — invites us to question the circulation of materials beyond these elite settings.36 If the libraries of the richest humanists had a very encyclopedic ambition, those more modest ones might have to stay close to the owners’ practices and social milieu.37 Pamela Smith has demonstrated that European artisans started acquiring books during the early modern period. Inventory records indicate an increase in book ownership among artisanal groups in the latter part of the sixteenth century. These books — usually recorded as “small books” in their collections — could have included not only the anticipated religious texts but also practical how-to, poetry, or history books that served as models in their everyday craft.38 Thus, studying smaller and more discrete collections, such as Ms. Fr 640, can provide new research avenues toward unexpected intellectual influences that may have driven experimentation and innovation in creating material objects.

This essay began with the premise of the uncertain nature of the list and explored four possible interpretations. The first hypothesis is that the list may represent a collection of physical books. This interpretation is supported by details about the publisher and List C’s title, “Books to Recover.” These elements suggest that at least part of the list could have had a physical form. The second and strongest hypothesis proposes that the list serves as a collection of references. It remains unclear how much of the list refers to existing works or an idealized representation. The list could function as a bibliographical representation driven by at least two motivations: first, the titles the author-practitioner intended to acquire, and second, references gathered from one or more authors or informants. The circulation of bibliographies during that century, particularly those by La Croix du Maine, is worth considering in this bibliographical endeavor.39 The third hypothesis suggests that the lists might be part of a more extensive collection, possibly linked to the donation made by Hyppolite de Béthune to the King of France. However, current research has not uncovered any references to these books within the will.40 Finally, the fourth hypothesis considers the possibility that the author-practitioner created a list of references to provide a scholarly foundation for a potential printed edition of a book of recipes. In this context, it is impossible to overlook the connection to the entry “Pour la Boutique,” where the author-practitioner also refers to Herodotus (fol. 162r).41

After a thorough reading of the references, we identified that they can be categorized into at least four distinct lists. Each list has specific characteristics that suggest they may have had different purposes and potentially different forms of material presentation. Furthermore, recognizing clusters of entries with geographic and thematic similarities within these lists indicates a less idiosyncratic material organization. For instance, List C contains a series of natural philosophy authors including Tilesius (Ms640.R76A), Marbodio (Ms640.R78A), and Albertus Magnus (Ms640.R78A), focusing on their works on minerals, colors, and stones.

The evidence for accepting or rejecting any of the hypotheses about the lists remains quite limited. Nevertheless, whether considering the ideal list of titles or a collection for a small library, the titles and authors reflect an intellectual reality of the sixteenth century. The author-practitioner likely worked in their scriptorium surrounded by various book references. As Hui suggests, “All libraries are real and imaginary.” The solitude of study encompasses both aspirations and material conditions.42 The list of titles and authors invites us to explore the connections between the titles, authors, and debates the author-practitioner engaged in his work. Despite the uncertainty surrounding these lists, they offer a pathway to intertextual connections between the author’s practice and the knowledge inherited through books.

Bibliography

Adams, Sean A. Greek Genres and Jewish Authors: Negotiating Literary Culture in The Greco-Roman Era. Texas: Baylor University Press, 2020.

Arnold, Jonathan. “John Colet and Polydore Vergil: Catholic Humanism and Ecclesiology.” Moreana 51, 197, 12 (2014): 138-165.

Babelon, Jean-Pierre. “Les Caravage de Philippe de Bethune.” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, vol. 11 (Jan.-Feb. 1988): 33-38.

Bartlett, John R. Jews in the Hellenistic World: Josephus, Aristeas, the Sibylline Oracles, Eupolemus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Bruder, Anthony J. “Guillaume Budé, Auteur Français: Medievalism and Humanism in the Institution Du Prince (1519).” French Studies 78, 3 (2024): 377-395.

Burke, Peter. A Social History of Knowledge. From Gutenberg to Diderot. Cambridge: Polity, 2001.

Camps, Celine and Margot Lyautey. “Ma<r>king and Knowing: Encoding BnF Ms. Fr. 640.” Making and Knowing Project. Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/cjhd-wh90.

Chartier, The Order of Books: Readers, Authors, and Libraries in Europe Between the Fourteenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford, CA.: Stanford University Press, 1994.

D’Amico, John F. Renaissance Humanism in Papal Rome: Humanists and Churchmen on The Eve of The Reformation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983.

Debuiche, Colin and Sarah Muñoz. “Ms. Fr. 640: The Toulouse Context.” Translated by Philippe Barré and Christine Julliot de la Morandière. Making and Knowing Project. Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_312_ie_19.

Delatour, Jérôme. Une bibliothèque humaniste au temps des guerres de religion : les livres de Claude Dupuy : d’après l’inventaire dressé par le libraire Denis Duval (1595). Paris : École des Chartes ; Villeurbanne : Éditions de l’ENSSIB, 1998.

Dyon, Soersha and Heather Wacha. “Turning Turtle: The Process of Translating BnF Ms. Fr. 640.” Making and Knowing Project. Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/1pw7-ax09.

Earley, Benjamin. “Herodotus in Renaissance France,” Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Herodotus in Antiquity and Beyond, 6 (2016): 120-142.

Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge, UK; New York, US: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Febvre, Lucien and Henri-Jean Martin*. L’apparition du livre*. Paris: A. Michel, 1999.

Gaida, Margaret. “Reading Cosmographia: Peter Apian’s Book-Instrument Hybrid and the Rise of the Mathematical Amateur in the Sixteenth Century.” Early Science and Medicine 21, 4 (2016): 277-302.

Grafton, Anthony. Commerce With the Classics: Ancient Books and Renaissance Readers. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2020.

Grafton, Anthony. “Polydore Vergil Uncovers the Jewish Origins of Christianity.” Inky Fingers: The Making of Books in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020, pp. 105-127.

Goody, Jack. The Domestication of the Savage Mind. Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Hirsch, Rudolf. “Printing in France and Humanism, 1470-80.” Gundersheimer, Werner L., ed. French humanism, 1470-1600. New York: Harper & Row, 1970, pp. 113-130.

Hui, Andrew. The Study: The Inner Life of Renaissance Libraries. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Kemezis, Adam M. “Multiple Authors and Puzzled Readers in the Historia Augusta.” Baumann, Mario and Vasileios Liotsakis, eds. Reading History in the Roman Empire. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2022, pp. 223-248.

Mazzocco, Angelo and Marc Laureys. A new sense of the past: the scholarship of Biondo Flavio (1392-1463). Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2016.

McKenzie, Donald F. “The Book as Expressive Form,” Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts. Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 9-30.

Martin, Henri-Jean. “What Parisians Read in the Sixteenth Century.” Gundersheimer, Werner L., ed. French humanism, 1470-1600. New York: Harper & Row, 1970, pp. 131-145.

Muecke, Frances. “Ancient Rome in Renaissance France: Around the Paris Edition of Biondo Flavio’s Roma Triumphans ([1532]–1533).” Australian Journal of French Studies 60, 4 (2023): 361-372

Nelles, Paul. “The Renaissance Ancient Library Tradition and Christian Antiquity” Smet, Rudolf de, ed. Les humanistes et leur bibliothèque: actes du colloque international, Bruxelles 26-28 août 1999. Sterling: Peeters, 2002, pp. 159-173.

Šamurin, E.I. Geschichte der bibliothekarisch-bibliographischen Klassifikation. Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig, 1964.

Smith, Pamela H. “An Introduction to Ms. Fr. 640 and its Author-Practitioner.” Making and Knowing Project. Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/ny3t-qg71

Smith, Pamela H. From Lived Experience to the Written Word. Reconstructing Practical Knowledge in the Early Modern World. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2022.

Smith, Tyler. “Josephus’s Jewish Antiquities in Competition with Nicolaus of Damascus’s Universal History,” Journal of Ancient Judaism 13, 1 (2022): 52-76

Stover, Justin A. and Mike Kestemont. “The Authorship of the Historia Augusta: Two New Computational Studies.” Bulletin - Institute of Classical Studies 59, 2 (2016): 140-157.

Wood, James B. “The Impact of the Wars of Religion: A View of France in 1581.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 15, 2 (1984): 131-168.

Appendix. Ms. Fr. 640 – Lists of References

List of Attributed Authors and Titles

| Order | List | Author | Book Title | Literal Transcription | Signature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | B | Wolfgang Laz | N/A | Vuolfangus Lazius | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 2 | B | Peter Apian | Cosmographicus liber Petri Apiani mathematici studiose collectus | Petrus appianus Mathemat | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 3 | B | Raffaele Maffaei | Commentariorum rerum urbanorum liber XXIIII | Ingolstadiensis Comment. urb. rom. | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 4 | B | Girolamo Ruscelli | Secreti Del Reverendo Donno Alessio Piemontese | Hieronimo Ruscelli | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 5 | B | Ermolao Barbaro | Castigationes Plinianae et Pomponii Melae | Hermolaus barbarus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 6 | B | Pietro degli Angeli | De Aucupio Liber Primus | Angelius Bargæus de aucupio et venatione | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 7 | B | Nicolaus of Damascus | Ex nicolai damasceni vniversali historia sev de moribus gentium libris excerpta iohannis stobaei, ed. Nicolaus Cragius | Nicolaus Damascenus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 8 | B | Procopius of Caesarea | De Rebus Gothorum, Persarum Ac Vandalorum Libri Vii | Cares de rebus persarum | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 9 | B | Isidore of Seville | N/A | Isidorus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 10 | B | Paulus Orosius | Historiae Adversus Paganos | Osorius | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 11 | B | Eupolemus | N/A | Eupolemus historicus gentilis / qui de rebus davidis & salomonis / scripsit | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 12 | B | Gilles Corrozet | Le Cathalogue Des Villes et Citez Assises Es Troys Gaulles | Cathalogue des villes | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 13 | B | Guy Marchant | Kompost et Kalendrier Des Bergiers | Calendrier des bergiers | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 14 | B | Jean-Pierre de Mesmes | La Grammaire Italienne, Composée En Françoys | Grammaire Italiene | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 15 | B | Pierre de Savonne | Nouvelle Instruction d’Arithmétique Abrégée | Arithmetique de Savonne | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 16 | B | Philibert Boyer | Instruction Pour Le Faict Des Finances | Instruction pour le faict des fina{n}ces | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 17 | B | Antoine Du Verdier | Questions Enigmatiques, Recreatives et Propres Pour Deviner et Y Passer Le Temps Aux Veillees Des Longues Nuicts | Questions Aenigmatiques | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 18 | B | Cassianus Bassus | Constantini Caesaris Selectarum Praeceptionum de Agricultura Libri Viginti | Des præceptes dagriculture | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 19 | B | Nicolas Froumenteau | Le Secret Des Finances de France | Le secret des finances a Lyon | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 20 | B | Synesius of Cyrene | N/A | Synesius | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 21 | B | Olaus Magnus | Historiae de Gentibus Septentrionalibus Libri Xxii | Olaus Magnus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 22 | B | Bernard Palissy | Discours admirables | M{estr}e Bernard palissi inventeur des rustiques figulines du roy / et de la royne mere | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 23 | A | Ippolito Salviani | Aquatilium Animalium Historiae Liber Primus | Aquatilium animalium historiæ hypolito / salviano / typhernate authore Romæ 1554 | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 24 | B | Jean Nagerel | Description du Pays et Duché de Normandie, | Les Annales de Normandie | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 25 | B | Alexander of Aphrodisias | Problemata | Alexander Aphrodisæus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 26 | B | Polydore Vergil | De Inventoribus Rerum | Polydorus verg. | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 27 | B | Appian | Historia Romana | Appianus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 28 | B | Athenaeus of Naucratis | Dipnosophistarum | Athenæus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 29 | B | Pausanias | Veteris Graeciae Descriptio | Pausanias | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 30 | B | Statius | Statii Syluarum libri quinque : Thebaidos libri duodecim : Achilleidos duo | Statius Thebaidos | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 31 | B | Servius | Commentarii in Vergili opera | Servius in Aeneid. | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 32 | B | Macrobius | Macrobii Aurelii Theodosii viri consularis In Somnium Scipionis libri duo: et septem eiusdem Saturnaliorum | Macrobius | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 33 | B | Aulus Gellius | Noctes Atticae | Aulus Gellius | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 34 | B | Alessandro Alessandri | Alexandri ab Alexandro iurisperiti Neapolitani Genialium dierum libri sex | Alexander ab Alex. | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 35 | B | Festus | De verborum significatione | Festus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 36 | B | Nonius Marcellus | De proprietate sermonum | Nonius | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 37 | B | Girolamo Maggi | Variarum Lectionum | Magius miscell. | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 38 | B | Julius Pollux | Onomasticon | Pollux onomast | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 39 | B | Gaius Julius Hyginus | Fabularum Liber Eiusdem Poeticon Astronomicon, Libri Quatuor | Higinus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 40 | B | Berosus | Berosus babillonic[us] de antiquitatibus Seu defloratio Berosi. Caldaic | Berosus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 41 | B | Suetonius | Duodecim Caesares: et De illustribus grammaticis, & claris rhetoribus, libelli duo | Suetonius | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 42 | B | Valerius Maximus | Dictorum factorumque memorabilium exempla | Valerius max. | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 43 | B | Tacitus | N/A | Cornelius tacitu | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 44 | B | Xenophon of Athens | N/A | Xenophon | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 45 | B | Seneca | N/A | Seneca | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 46 | B | Dionysos of Halicarnassus | De origine urbis romæ, & romanarum rerum antiquitate | Dionisius Halicarnassensis | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 47 | B | Sabellicus | Opera omnia, | Sabellicus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 48 | B | Julius Capitolinus | Historia Augusta | Iulius Capitollin{us} | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 49 | B | Guillaume Budé | De asse et partibus eius libri quinque | Budæus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 50 | B | Spartianus | Historia Augusta | Spartianus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 51 | B | Flavio Biondo | De Roma triumphante libri decem | Blondus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 52 | B | Raffaele Maffaei | Commentariorum rerum urbanorum liber XXIIII | Volaterranus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 53 | B | Herodotus | Histories | Herodotus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 54 | B | Paulus Manutius | Antiquitatum Romanarum Paulli Mannuccii Liber de Senatu | Paulus Manutius | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 55 | B | Strabo | Strabonis illustrissimi scriptoris Geographia decem et septem libros co[n]tinens | Strabo | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 56 | B | Julius Firmicus | Astronomicωn Lib. VIII | Iulius firmicus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 57 | B | Quintus Curtius Rufus | Historiae Alexandri Magni | Quintus Curtius | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 58 | B | Cassius Dio | Dion historien grec, des faictz et gestes insignes des Romains | Dion | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 59 | B | Cornelius Nepos | De viris illustribus | Cornelius Nepos | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 60 | B | Flavius Vopiscus | Historia Augusta | Flavius Vopiscus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 2 |

| 61 | D | Claude Guichard | Funérailles et Diverses Manieres d’ensevelir Des Romains, Grecs, et Autres Nations | Trompettes voy le livre des funerailles | Ms Fr 640, fol. 1r, col. 1 |

| 62 | C | Sigebert de Gembloux | Chronicon Ab Anno 381 Ad 1113, Cum Insertionibus Ex Historia Galfridi et Additionibus Roberti, Abbatis Montis, Centum et Tres Sequentes Annos Complectentibus, Promovente Egregio Patre d. G. Parvo,\... Nunc Primum in Lucem Emissum | Les chroniques de Sigebert | Ms Fr 640, fol. 2r |

| 63 | C | Tyrannius Rufinus | Opuscula quædam | Ruffinus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 2r |

| 64 | C | Irenaeus | Opus in Quinque Libros Digestum, in Quibus Mire Retegit & Confutat Veterum Haereseon Impias Ac Por Tentosas Opiniones | Irenius in Exegesi | Ms Fr 640, fol. 2r |

| 65 | C | Paulus Aemilius Veronensis | Pauli Aemilii Veronensis, historici clarissimi, De rebus gestis Francorum | Paule Emile | Ms Fr 640, fol. 2r |

| 66 | C | Paolo Giovio | N/A | Paule Jove | Ms Fr 640, fol. 2r |

| 67 | C | Polydore Vergil | De Inventoribus Rerum | Polydorus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 2r |

| 68 | C | Giacomo Filippo Foresti | Supplementum chronicarum | Bergomensis | Ms Fr 640, fol. 2r |

| 69 | C | Philippes de commines | Cronicque et Histoyre | Philippes de commines | Ms Fr 640, fol. 2r |

| 70 | D | Otto I of Freising | Chronicon sive rerum ab orbe condito ad sua usque tempora gestarum | Othonis Epi{scopi} / frisigensis / ab orbe condito | Ms Fr 640, fol. 170v |

| 71 | D | Conrad of Lichtenau | Chronicum abbatis urspergensis, a nino rege assyriorum magno, usque ad fridericum ii.romanorum imperatorem | Abbatis / Uspergensis / Chronic. | Ms Fr 640, fol. 170v |

| 72 | D | Mercuriali | Variarum lectionum | Hyeronimus / mercurialis / variarum | Ms Fr 640, fol. 170v |

| 73 | A | George Buchanan | Rerum Scoticarum Historia Auctore Georgio Buchanano Scoto | Reru{m} scoticarum historia / Georgio Bucanano / auth. | Ms Fr 640, fol. 170v |

| 74 | A | Dodoens | Trium Priorum de Stirpium Historia Commentariorum Imagines Ad Vivum Expressae Una Cum Indicibus, Graece, Latine, Officinarum, Germanica, Brabantica Gallicaque Nomina Complectentibus | Rembertus Dodonæus mechliniensis medicus de stirpium historia | Ms Fr 640, fol. 170v |

| 75 | A | Philibert de l’Orme | Nouvelles Inventions Pour Bien Bastir et a Petits Fraiz | Des ormes de linvention de bien bastir et aultres oeuvres | Ms Fr 640, fol. 170v |

| 76 | A | Simone Porzio; Bernardino Telesio | De coloribus libellus, Latinitate donatus, et commentariis illustratus una cum praefatione, qua coloris naturam declarat | Tilesius / de coloribus Vascosan | Ms Fr 640, fol. 170v |

| 77 | A | Marbodus Redonensis | Libellus de Lapidibus Preciosis | Marmodæus ge de lapillis præciosis | Ms Fr 640, fol. 170v |

| 78 | A | Albertus Magnus | De mineralibus | Albertus magnus de mineralibus | Ms Fr 640, fol. 170v |

| 79 | D | Girolamo Vida of Cremona, | Bucolica de Bombyce Ad Isabellam Estensem Marchionissam Libri II | See Hieronymus Vida Albensis ep{iscop}us de b Cremonensis scripsit carmine de bombicum natura. | Ms Fr 640, fol. 53v |

| 80 | D | Matthiolus | Commentaires de M. Pierre André Matthiole Médecin Sennois, | Faictes seicher de la racine de pied de veau aultrem{ent} jarus & en saulpouldres la viandes a quoy il ny a poinct de dangier Voy Mathiol | Ms Fr 640, fol. 35v |

This manuscript entered the collection of the Bibliothèque du Roi, the precursor to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, in the mid-seventeenth century. Dating from the late sixteenth century and written in French, this book contains over nine hundred entries covering various crafts. Notably, it focuses on metallurgical and casting practices, but it also includes topics such as painting, metal processing, varnishing, armor-making, medicine, and coloring, among many others. Pamela H. Smith, “An Introduction to Ms. Fr. 640 and its Author-Practitioner,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/ny3t-qg71 ↩︎

The reference code consists of three parts: the source (Ms640), a unique reference number (R1-R80), and the category to which it belongs (A-D). This system will be used consistently throughout the article, with an explanation of the criteria for creating this coding. For the complete list of references, please refer to the appendix. ↩︎

Making and Knowing Project et al., Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Critical Digital Edition of BnF Ms 640, fol. 170v (Accessed, November 10, 2024). https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/folios/170v ↩︎

Andrew Hui, The Study: The Inner Life of Renaissance Libraries (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2024), 14. ↩︎

Jack Goody, The Domestication of the Savage Mind (Cambridge University Press, 1977), 103. ↩︎

Chartier, The Order of Books: Readers, Authors, and Libraries in Europe Between the Fourteenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Stanford, CA.: Stanford University Press, 1994), viii. Anthony Grafton, Commerce with the Classics: Ancient Books and Renaissance Readers (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2020), 19. ↩︎

See Appendix. ↩︎

About the material approach to book history, McKenzie proposes that “A ‘sociology of texts’, […] contrasts with a bibliography confined to logical inference from printed signs as arbitrary marks on parchment or paper. As I indicated earlier, claims were made for the ‘scientific’ status of the latter precisely because it worked only from the physical evidence of books themselves.” Donald F. McKenzie, “The Book as Expressive Form,” in Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts (Cambridge University Press, 2004), 15. ↩︎

On the encoding of digital critical edition of Ms. Fr. 640, see Celine Camps and Margot Lyautey, “Ma<r>king and Knowing: Encoding BnF Ms. Fr. 640,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/cjhd-wh90. ↩︎

On the translation of Ms. Fr. 640, see Soersha Dyon and Heather Wacha, “Turning Turtle: The Process of Translating BnF Ms. Fr. 640,” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/1pw7-ax09. ↩︎

Goody, The Domestication of the Savage Mind, 71-73. ↩︎

Goody, The Domestication of the Savage Mind, 81. ↩︎

Chartier builds upon Foucault’s essay “What is an Author?” and analyses the juridical, repressive, and material transformation that led to a novel understanding of literary authorship in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Chartier, The Order of Books, 26-59. ↩︎

Smith, “An Introduction to Ms. Fr. 640,” DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/ny3t-qg71. ↩︎

“Eupolemus scripsit acta Davidis & Salomonis.” Andreas Masius, “Index V. Generalis ex eourum quae ad Rem”, Josuae Imperatoris Historia Illustrata Atq. Explicata Ab Andrea Masio (Antwerp: Christophorus Plantinus, 1574) ↩︎

E.I. Šamurin, Geschichte der bibliothekarisch-bibliographischen Klassifikation (Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig, 1964), 45-48. ↩︎

Šamurin, Geschichte der bibliothekarisch-bibliographischen Klassifikation, 111-113. ↩︎

Peter Burke, A Social History of Knowledge. From Gutenberg to Diderot (Cambridge: Polity, 2001), 92-93. ↩︎

Chartier, The Order of Books, 71-72. ↩︎

Šamurin, Geschichte der bibliothekarisch-bibliographischen Klassifikation, 118-123. ↩︎

Burke, A Social History of Knowledge, 162-163. ↩︎

For current debates about the authorship of Historia Augusta, see Adam M. Kemezis, “Multiple Authors and Puzzled Readers in the Historia Augusta,” in Reading History in the Roman Empire, edited by Mario Baumann and Vasileios Liotsakis (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2022), 223-250; Justin A. Stover and Mike Kestemont, “The Authorship of the Historia Augusta: Two New Computational Studies,” Bulletin - Institute of Classical Studies 59, 2 (2016): 140-157. ↩︎

Frances Muecke, “Ancient Rome in Renaissance France: Around the Paris Edition of Biondo Flavio’s Roma Triumphans ([1532]–1533),” Australian Journal of French Studies 60, 4 (2023): 367-368; Angelo Mazzocco and Marc Laureys, A new sense of the past: the scholarship of Biondo Flavio (1392-1463) (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2016), 182-183. ↩︎

About Secrets de finances, James Wood says, “Le secret des finances has been attributed to two authors, Nicholas Bernaud and Jean Frotte. Bernaud, a Calvinist polemicist with hermetic tendencies, however, was living in Geneva in 1581, and his truly peripatetic wanderings would seem to have made almost impossible sufficient access to the obvious sources for such a massive statistical work. Jean Frotte appears to be a more reasonable candidate. Frotte, who began his career as maître d’hôtel et des comptes for the Constable Bourbon, became, after the disgrace of the latter, secretaire des finances of Marguerite d’Angouleme, queen of Navarre, sister of Francis I. He was named secretaire de roi in 1541, an office which he actually exercised from 1549 (after Margaret’s death) until his resignation in 1560, after the death of Henry II. A known Calvinist, whose five sons also adhered to the Huguenot party, and author of Le miroir des Français, also published in 1581, Frotte had sufficient expertise, opportunity, and motivation such that the attribution to him of Le secret des finances appears reasonably certain.” James B. Wood, “The Impact of the Wars of Religion: A View of France in 1581,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 15, 2 (1984): 132. ↩︎

Tyler. Smith, “Josephus’s Jewish Antiquities in Competition with Nicolaus of Damascus’s Universal History,” Journal of ancient Judaism 13, 1 (2022): 52-54; John R. Bartlett, Jews in the Hellenistic world: Josephus, Aristeas, the Sibylline oracles, Eupolemus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985); Sean A. Adams, Greek Genres and Jewish Authors: Negotiating Literary Culture in The Greco-Roman Era (Texas: Baylor University Press, 2020) 254-256. ↩︎

About the renewed interest on ancient libraries during the Renaissance, see Paul Nelles, “The Renaissance Ancient Library Tradition and Christian Antiquity,” in Les humanistes et leur bibliothèque: actes du colloque international, Bruxelles 26-28 août 1999, edited by Rudolf de Smet (Sterling: Peeters, 2002), 159-173. ↩︎

About Polydore Vergil, see Jonathan Arnold, “John Colet and Polydore Vergil: Catholic Humanism and Ecclesiology,” Moreana 51, 197-12 (2014): 138-165; Anthony Grafton, “Chapter 4. Polydore Vergil Uncovers the Jewish Origins of Christianity,” Inky Fingers: The Making of Books in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020), 105-127. On Budé, see Anthony J. Bruder, “Guillaume Budé, Auteur Français: Medievalism and Humanism in the Institution Du Prince (1519),” French Studies 78, 3 (2024): 377-395; Anthony Grafton, “Chapter 4,” Commerce with the Classics: Ancient Books and Renaissance Readers (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2020). ↩︎

Margaret Gaida, “Reading Cosmographia: Peter Apian’s Book-Instrument Hybrid and the Rise of the Mathematical Amateur in the Sixteenth Century,” Early Science and Medicine 21, 4 (2016): 277-302. ↩︎

John F. D’Amico reminds how Maffei is considered representative of Roman humanism and his Commentaria Urbana is regarded as one of the first encyclopedias. D’Amico, Renaissance humanism in papal Rome: humanists and churchmen on the eve of the Reformation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983), xvii, 183. ↩︎

For an analysis of the manuscript in Toulouse’s context, see: Colin Debuiche and Sarah Muñoz, “Ms. Fr. 640: The Toulouse Context,” translated by Philippe Barré and Christine Julliot de la Morandière, in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020), https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_312_ie_19. ↩︎

Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The printing revolution in early modern Europe (Cambridge, UK; New York, US: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 291-293. ↩︎

Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, L’apparition du livre (Paris: A. Michel, 1999), 39-109. ↩︎

Rudolf Hirsch, “Printing in France and Humanism, 1470-80,” in French humanism, 1470-1600 edited by Werner L. Gundersheimer (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), 115. ↩︎

Burke, A Social History of Knowledge, 162-163. ↩︎

Rudolf Hirsch, “Printing in France and Humanism,” 122-123. ↩︎

Henri-Jean Martin builds these conclusions upon the study of Roger Doucet*, Les Bibliotheques parisiennes au XVIe siecle* (Paris, A. & J. Picard: 1956), Alexander Schutz, Vernacular Books in Parisian Private Libraries of the Sixteenth Century (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press; and Geneva, Librairie Droz: 1955), and Françoise Lehoux*, Gaston Olivier, aumónier du roi Henri II, Bibliotheque parisienne et mobilier du XVIe siècle* (Paris, l’auteur,: 1957). Henri-Jean Martin, “What Parisians Read in the Sixteenth Century,” in French humanism, 1470-1600 edited by Werner L. Gundersheimer (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), 144. The analysis of those sectors of the literate society has shown there were considerable libraries that included the works of Erasmus, Guillaume Budé, Pico de la Mirandola, Moore, Boccaccio, Petrarch, or Lorenzo Valla, some of which also appear in the list of Ms. Fr. 640. Most of these studies aggregate results from several libraries’ quantitative analyses, but others focused on relevant figures for a more nuanced approach. ↩︎

Jérôme Delatour, Une bibliothèque humaniste au temps des guerres de religion : les livres de Claude Dupuy : d’après l’inventaire dressé par le libraire Denis Duval (1595) (Paris : École des Chartes ; Villeurbanne : Éditions de l’ENSSIB, 1998), 96-100. ↩︎

Pamela Smith, From Lived Experience to the Written Word. Reconstructing Practical Knowledge in the Early Modern World (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2022), 164-166. ↩︎

Chartier, The Order of Books, 66-68. ↩︎

The inventory of Philippe de Bethune dated 19 November 1608 is Archives Nationales, minutier central, XIX, 366, discussed by Jean-Pierre Babelon in “Les Caravage de Philippe de Bethune,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, vol. 11 (Jan.-Feb. 1988), pp. 33-38. ↩︎

About the place of Herodotus during humanism and Renaissance, see Benjamin Earley, “Herodotus in Renaissance France,” in Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Herodotus in Antiquity and Beyond, 6 (2016): 120-142. ↩︎

Hui, The Study, 24. ↩︎