STUCCO FOR MOLDING RECONSTRUCTION

HIST GR8906: Craft and Science: Making Objects in the Early Modern World | Ephemeral Art in BnF Ms. Fr. 640

The Making and Knowing Project, Columbia University

Last updated 2021-09-24 by NJR

A downloadable version of this assignment: [PDF]

NOTE TO INSTRUCTORS: Rather than providing the full instructions, one may want to provide students only with the original recipe and the materials, allowing them to interpret the entry for themselves. A “student handout” is available:

Ephemeral Art in BnF Ms. Fr. 640

The 16th-century artisanal/technical manual, BnF Ms. Fr. 640, contains hundreds of entries that describe making processes and techniques from the Renaissance. These include instructions for and observations about painting, gilding, arms and armor production, plant cultivation, and making molds and metal casts.

Among other topics, the manuscript offers insight into the cultural context, materials, and techniques of ephemeral artworks. Several entries in the manuscript aim to produce artworks that were intended to stand outside or that aimed to create the visual effect of a more permanent (and expensive) work of art. Explore the full range of topics in Ms. Fr. 640 in Secrets of Craft and Nature. A Digital Critical Edition of BnF Ms. Fr. 640.

Stucco for Molding

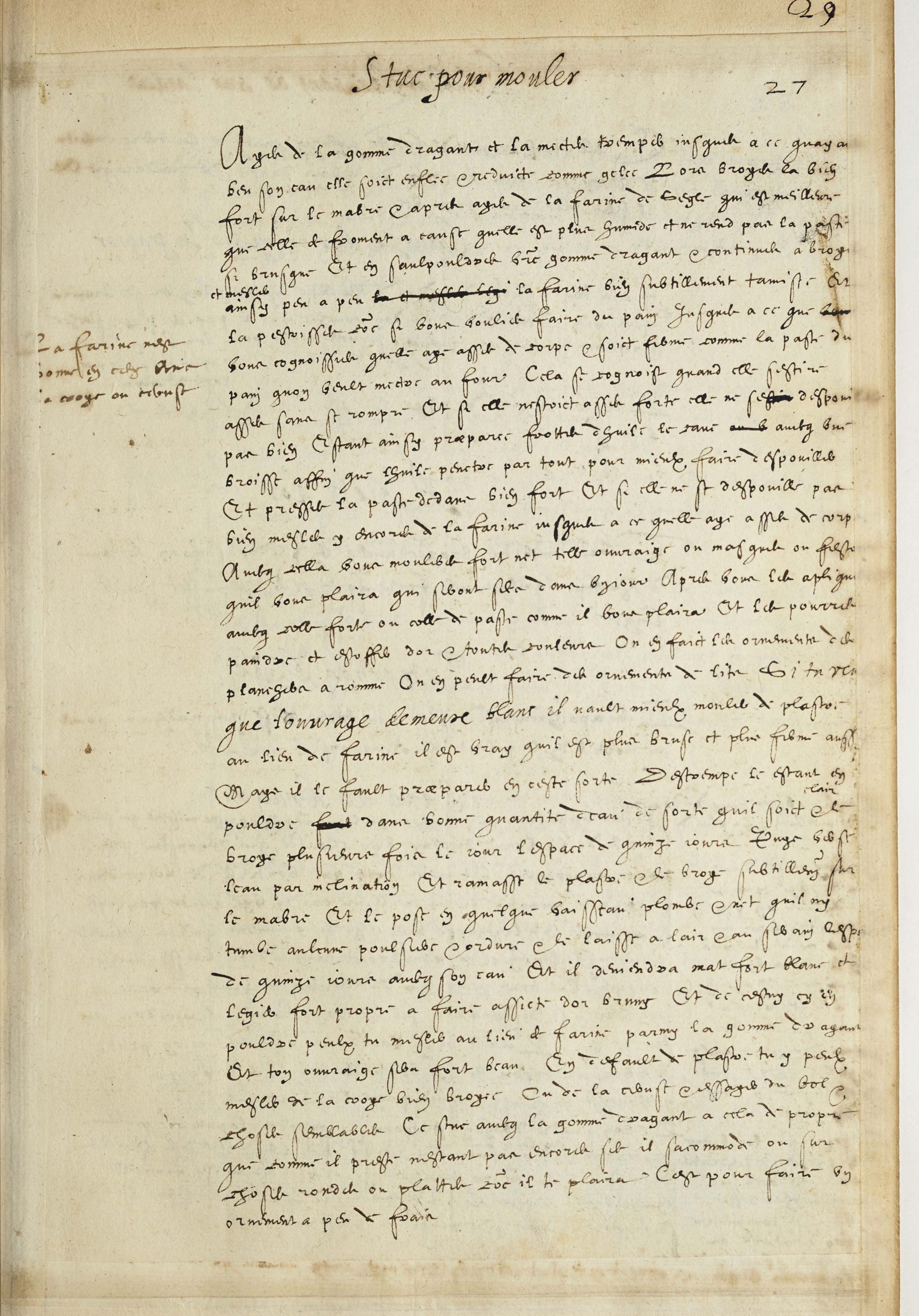

On folio 29r, an entry describes a process for making stucco to create “an ornament at little expense.”

| Facsimile | Translation |

|---|---|

| Stucco for molding Take tragacanth gum and put it to soak until, having drunk its water, it is swollen & rendered like jelly. Then grind it quite hard on marble & next take rye flour, which is better than wheat because it is more humid and does not make the paste as brittle, and sprinkle your tragacanth gum with it, & continue to grind and mix in thus, little by little, If you want that the work stays white, it is better to mold with plaster instead of flour. It is true that it is more brittle and firm as well, but one needs to prepare it like this: temper it, when it is powdered At the top left margin: Flour is not good in this, but chalk or ceruse is. |

The entry details a general process: create a jelly from tragacanth gum and water, mix in a powdered material, then press the mixture into a mold. This process can be adapted for a few variations: creating stucco from flour, from plaster, from chalk, and from ceruse (lead white).

NOTE TO INSTRUCTORS: Rather than providing the full instructions, one may want to provide students only with the original recipe and the materials, allowing them to interpret the entry for themselves.

Materials and Equipment

The reconstruction of this recipe has been adapted for two variations: stucco from flour and stucco from chalk. The ratios suggested here are approximations based on prior experiments by the Making and Knowing Project.

Materials

- 1:14 tragacanth gum to water

- FLOUR: Approximately 3:4 ratio gum/water to rye flour OR CHALK: approximately 2:5 ratio gum/water to chalk

- Linseed oil (or another vegetable oil) to lubricate the molds

- Mineral spirits (to clean brushes and molds)

Equipment

- Scale and weigh boats (to measure ingredients)

- Containers, bowls, or beakers for materials

- Glass muller

- Glass plate

- Spoon, palette knife, or chopstick for mixing

- Sieve with fine mesh

- Container to sieve flour into

- Brush and small container (to spread oil)

- Plastic or silicone molds

- Flat surface where stucco can be left to dry

- Lidded containers to store molded stucco pieces

Instructions

The reconstruction of this recipe has been adapted for two variations: stucco from flour and stucco from chalk. The first and last step are the same for both, but the second step is slightly different depending on whether you are making the flour or the chalk variation.

Step 1: Tragacanth gum paste (1:14 ratio gum to water)

- Add tragacanth gum to water while mixing. The powder will not easily incorporate into the water, so allow the gum to “drink its water” until is “swollen and like jelly.”

- Stir the mixture until it is a cohesive mass, then transfer it to a plate and mull with a muller until smooth and the mixture resembles the texture of petroleum jelly.

Step 2: Stucco | OPTION 1: Rye flour (approximately 3:4 ratio gum/water to rye flour)

- Sift the flour with a fine mesh to remove larger pieces.

- Into the tragacanth gum and water mixture, begin to incorporate the sifted flour on the glass plate. Mix first with a palette knife or spoon, then work it with your hands, treating it like dough.

- Add flour until the stucco is malleable yet firm and can be “kneaded” to become smooth and homogeneous.

Step 2: Stucco | OPTION 2: Chalk (approximately 2:5 ratio gum/water to chalk)

- Into the tragacanth gum and water mixture, begin to incorporate the chalk on the glass plate. Mix first with a palette knife or spoon, then work it with your hands, treating it like dough.

- Add chalk until the stucco is malleable yet firm and can be “kneaded” to become smooth and homogeneous.

Step 3: Molding

- To prepare the molds for the stucco, use a soft brush to lightly oil the silicone or plastic molds with linseed oil, making sure to cover all surfaces and crevices of the mold with a very thin layer of oil.

- Take a ball of the prepared stucco dough that is slightly larger in volume than the mold.

- Press the ball into the mold, ensuring that dough has reached every crevice

- Carefully remove the molded dough from the mold and leave to dry overnight, impression-side up.

Further reading:

- Elizondo-Garza, Nina. “Stucco for Molding.” In Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/essays/ann_064_fa_17. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.7916/1n6h-5f69.

A downloadable version of this assignment: [PDF]

NOTE TO INSTRUCTORS: Rather than providing the full instructions, one may want to provide students only with the original recipe and the materials, allowing them to interpret the entry for themselves. A “student handout” is available: