MAKING LAKE PIGMENT FROM COCHINEAL: A HISTORICAL RECONSTRUCTION

The Making and Knowing Project, Columbia University

Last updated 2021-09-29 by NJR

A downloadable version of this assignment: [PDF]

Lake pigments and natural colorants

If you are not already familiar with historical pigments and natural colorants, refer to Presentation: Cochineal Lake: History, Chemistry, and Preparation for more complete information and further explanation of natural colorants and lake pigments.

See also Presentation: Introduction to Pigments & Paints.

Lake pigments are a type of pigment prepared from organic natural colorants: plant and animal sources. As most organic natural colorants are soluble, they cannot be mixed directly with a binding medium and therefore cannot be used as a pigment. These colorants must therefore be extracted and then made insoluble in order to use them as pigments.

Lake pigments: in general, pigments prepared from soluble natural colorants, formed by precipitating (or adsorbing) the dye onto a colorless or white, insoluble, relatively inert substrate.

Jo Kirby et al, Natural Colorants for Dyeing and Lake Pigments: Practical Recipes and their Historical Sources (Archetype, London, 2014).

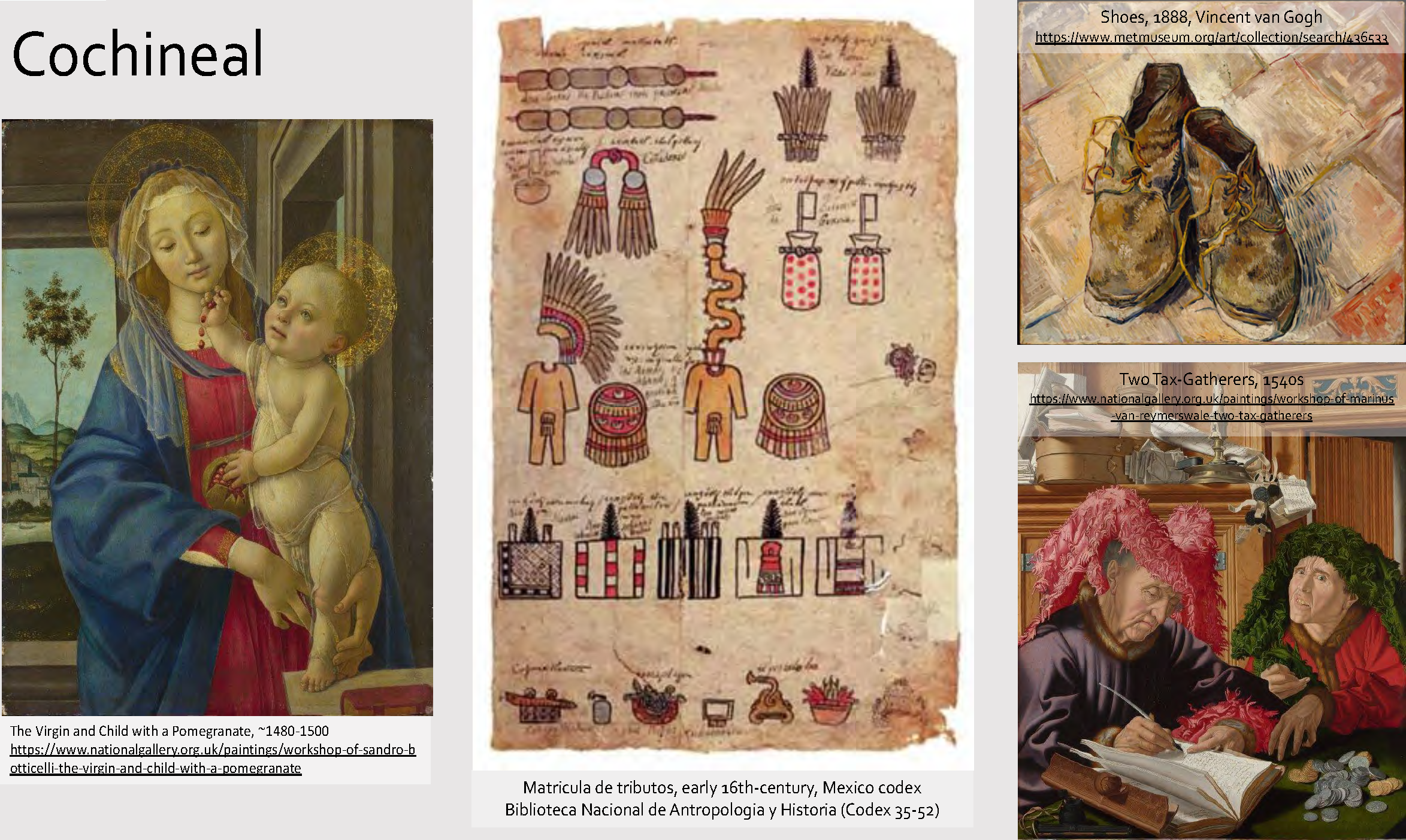

Cochineal

Cochineal, covered in a white excretion that acts as a protective layer, on a nopal pad (Naomi Rosenkranz, Altadena, CA, 2023)

Cochineal is a scale insect found on prickly pear or Barbary fig cactus (Opuntia ficusindica (L.)).

Species name: Dactylopius coccus

Chemical class: carminic acid (anthraquinone)

Region: Cultivated in Mexico and Peruvian Andes, before Spain brought to Europe in 1523 where it spread rapidly.

Phipps, Elena. Cochineal Red: the Art History of a Color. New York (N.Y.: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010. Print.)

Examples of cochineal in art

Cochineal insects have been used for centuries in the Americas as both a red dye and pigment. In the sixteenth century, when they were first brought to Europe, their use proliferated and even continues to this day all around the world.

Historical recipe for cochineal lake

The “Paduan Manuscript” (anonymous, Venice, late 16th-17th century)

Mary P. Merrifield, Medieval and Renaissance Treatises on the Arts of Painting: Original Texts with English Translations (1849, Dover Publications, 1969), pp. 701-702.

Another sort of fine lake. Take 12 grains of powdered cochineal or fine grana, add to it 2oz of ley; leave the infusion for about 2 hours; strain it through a linen cloth and put it over hot cinders; When it boils add to it pulverized roche alum of the size of 2 peas then the ley will make a thick red scum; as soon as this happens throw it all onto a stretched linen cloth, when the clear ley will pass through leaving the coagulum on the cloth, which coagulum must afterwards be dried and made into tablets.

Un altra sorte di lacca fina. - R. Piglia 12 grani di cocciniglia, o grana fina fatta inpolvere, si pone in due oncie di lissivio lasciandola in infusione due hore incirca poi si cola per pano lino, e si mette sopra cenere calda, quando vorrà bollire vi si aggiunge quanto due piselli d'allume di rocca in polvere, quando il liscivo farà schiuma grossa incarnata all' hora si getta tutto in un panno lino steso, e passarà il lissivo chiaro restando la schiuma nel panno, quale si fa seccare, e si fa tavolette.

Modernized recipes, adapted for the laboratory (or kitchen)

The following recipes have been adapted from Chapter 5, “Recipes,” of Jo Kirby et al, Natural Colorants for Dyeing and Lake Pigments: Practical Recipes and their Historical Sources (Archetype, London, 2014).

There are two modernized versions of this recipe:

- “Standard”

- Extraction of cochineal in potash, precipitation of pigment with alum

- “Standard Reversed”

- Extraction of cochineal in alum, precipitation of pigment with potash

RECIPE 1: “Standard”

Materials and Equipment (Recipe 1)

- Mortar & pestle

- Hot plate

- Large beaker (at least 1000ml)

- Small beaker (at least 100ml)

- Pair of chopsticks or other stirring device

- Thermometer

- Funnel

- Filter (such as a basket coffee filter) or filter paper

- pH strips

- 300ml Water - for potash (large beaker)

- 50ml Water - for alum (smaller beaker)

- Drawstring bag (such as a disposable tea bag)

- 0.24g Cochineal (the Making and Knowing Project typically sources this from Kremer Pigments, Kremer #36040-cochineal)

- 10g Alum (aluminum potassium sulfate, Kremer #64100-potash-alum)

- 4g Potash (potassium carbonate, Kremer #64040-potash)

Procedure (Recipe 1)

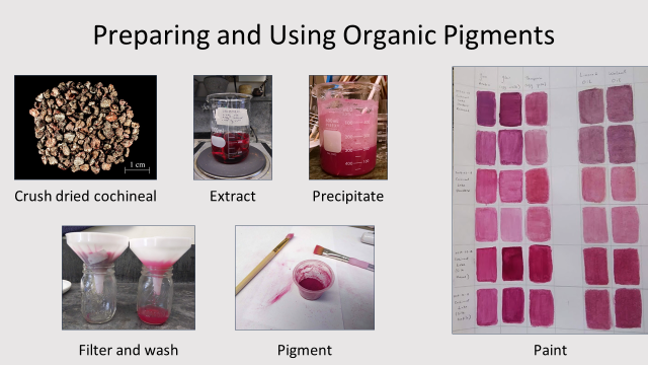

- Grind cochineal in mortar and pestle

- Using a small utensil, add cochineal to the drawstring bag. Close the bag tightly

- Add potash and bag of cochineal to 300ml water in the 1000ml beaker

- Bring to a boil and boil for 15-20 min

- Using heat, dissolve 10g alum in 50 ml water in the 100ml beaker

- Remove the drawstring bag containing the cochineal from the beaker. It can now be discarded

- Add the alum solution very gradually, stirring constantly to the cochineal+potash solution

- Do this slowly and incrementally, checking the pH of the solution after each addition until a pH of 6-7, there is no further effervescence, and precipitation of the lake pigment appears to be complete

- Allow the solution to settle for at least 15min (ideally overnight)

- Pour solution through filter in a funnel

- Once the liquid has drained through, wash the pigment: discard the filtrate and place funnel+filter over a clean container. Pour 100ml of clean water through the filter. Repeat until the filtrate is clear

- Allow the pigment to dry on the filter (at least overnight), then scrape off and use

RECIPE 2: “Standard - Reversed”

Materials and Equipment (Recipe 2)

- Mortar & pestle

- Hot plate

- Large beaker (at least 1000ml)

- Small beaker (at least 100ml)

- Pair of chopsticks or other stirring device

- Thermometer

- Funnel

- Filter (such as a basket coffee filter) or filter paper

- pH strips

- 300ml Water - for alum (large beaker)

- 50ml Water - for potash (smaller beaker)

- Drawstring bag (such as a disposable tea bag)

- 0.24g Cochineal (the Making and Knowing Project typically sources this from Kremer Pigments, Kremer #36040-cochineal)

- 10g Alum (aluminum potassium sulfate, Kremer #64100-potash-alum)

- 4g Potash (potassium carbonate, Kremer #64040-potash)

Procedure (Recipe 2)

- Grind cochineal in mortar and pestle

- Using a small utensil, add cochineal to the drawstring bag. Close the bag tightly

- Add alum and bag of cochineal to 300ml water in the 1000ml beaker

- Bring to a boil and boil for 15-20 min

- Using heat, dissolve 4g potash in 50 ml water in the 100ml beaker

- Remove the drawstring bag containing the cochineal from the beaker. It can now be discarded

- Add the potash solution very gradually, stirring constantly to the cochineal+alum solution

- Do this slowly and incrementally, checking the pH of the solution after each addition until a pH of 6-7, there is no further effervescence, and precipitation of the lake pigment appears to be complete

- Allow the solution to settle for at least 15min (ideally overnight)

- Pour solution through filter in a funnel

- Once the liquid has drained through, wash the pigment: discard the filtrate and place funnel+filter over a clean container. Pour 100ml of clean water through the filter. Repeat until the filtrate is clear

- Allow the pigment to dry on the filter (at least overnight), then scrape off and use

An Alternative Method To Using Hotplates and Beakers

If you do not have access to hotplates and heat-safe glass beakers, an alternative method uses a water bath or bain-marie (see this cooking blog for more information about bain-maries).

Process

- On your stove at home, prepare your solutions in mason jars (or other glass jars that can withstand prolonged heating such as pickling or jam jars).

- Place the jars in a large cooking pot (the pot’s material doesn’t matter – can use steel, ceramic, etc.)

- NOTE: be careful about using these pots to prepare foods after you have dyed with them if you are working with materials that are not food safe.

- NOTE: the natural colorants can stain light-colored surfaces, so be careful if using ceramic or glass pots.

- Fill the pot with enough water to come up past the solutions in your mason jars, being careful not to contaminate the solutions inside your jars

- Heat the pot on your stove and follow the procedure for preparing lake pigments

Advantages and Notes

- This is one way to prepare pigments at home without beakers or other shock-resistant containers

- Beakers, Pyrex, and other borosilicate glass is specially formulated to withstand direct high heat (like when placed directly on a hot plate) as well as shocks or sudden changes in temperature (like placing a hot glass vessel with your bath onto a cold surface like a counter)

- Regular glass, including mason jars, are not formulated in this way, and so it can be very dangerous (and messy) if used in the same way as beakers – direct high heat or sudden change can cause the glass to shatter

- This method also allows for easier preparation without a thermometer

- The temperature of your baths is determined by the temperature of the water in the pot

- You will know the baths have approximately reached the desired temperature range of 80-100 °C when the water in the pot is beginning to simmer

- Because water boils and begins to evaporate at 100 °C, your solutions will never exceed 100 °C, the temperature at which the colorants can begin to degrade. This is an easy way to prepare solutions without a thermometer and ensure you are not reaching high temperature levels

- If the water in the pot begins to boil or simmer violently, your jars will start to shake and move around the pot. If this happens, it is a sign to turn your heat down