Bread Making, Molding, and Casting (for the Instructor)

Introduction

The sixteenth-century artisanal/technical manual, BnF Ms. Fr. 640, contains hundreds of entries that describe making processes and techniques from the Renaissance. These include instructions for and observations about painting, gilding, arms and armor production, plant cultivation, and making molds and metal casts.

Ms. Fr. 640 contains three mentions of bread as a material that can be used to take an impression of another object quickly and neatly. This impression can be used as a mold into which sulfur or wax is cast. It is an example of the kind of intermediate process that artists must have relied on in the sixteenth century, akin to making a 3D printed prototype in resin before casting in gold for a modern jeweler, but for which very little historical evidence survives.

There are two entries for breadmolding on fol. 140v. Another on fol. 156r mentions breadmolding as an alternative process for “Molding promptly.”

| Folio | Translation |

|---|---|

| 140v | For casting in sulfur To cast neatly in sulfur, arrange the bread pith under thebrazier, as you know. Mold in it what you want & let dry, & you will have very neat work. Molding and shrinking a large figure Mold it with bread pith coming from the oven, or as the aforesaid,

& in drying out, it will shrink & consequently the medal that

you will cast in it. You |

| 156r | Molding promptly and reducing a hollow form to a relief You can imprint the relief of a medal in colored wax, & you will have a hollow form, in which you can cast en noyau a relief of your sand, on which you will make a hollow form of lead or tin, in which you will cast a wax relief. And then on that wax you will make your mold en noyau hollow, to cast there the relief of gold & silver or any other metal you like. But to hasten your work if you are in a hurry, make the first imprint & hollow form in bread pith, prepared as you know, which will mold very neatly. And into that, cast in melted wax, which will give you a beautiful relief on which you will make your noyau. |

This activity takes up relatively little class time and uses familiar materials such as bread and wax (the sulfur is optional and requires access to a fume hood or an open air space). The results are quick to achieve and are striking; this can be a very easy and successful hands-on activity to encourage confidence and it illustrates how hands-on making raises new questions. It can be done as a one-off activity in person or remotely, or works well as a skillbuilding exercise early in a longer course.

Learning Objectives

The activity introduces students to hands-on historical reconstruction and performative interpretation of texts. It is a good exercise to jump-start discussions of tacit/embodied knowledge in the arts and sciences. It is also an instructive introduction to the principles of molding. More generally, it encourages students to think differently about historical materials and processes, by de-familiarizing something we take for granted as food, and exploring its varied uses in everyday life, medicine, artistic practice, and the workshop.

This activity is split into 2 parts, the first part can be done asynchronously in advance of the in-class activity:

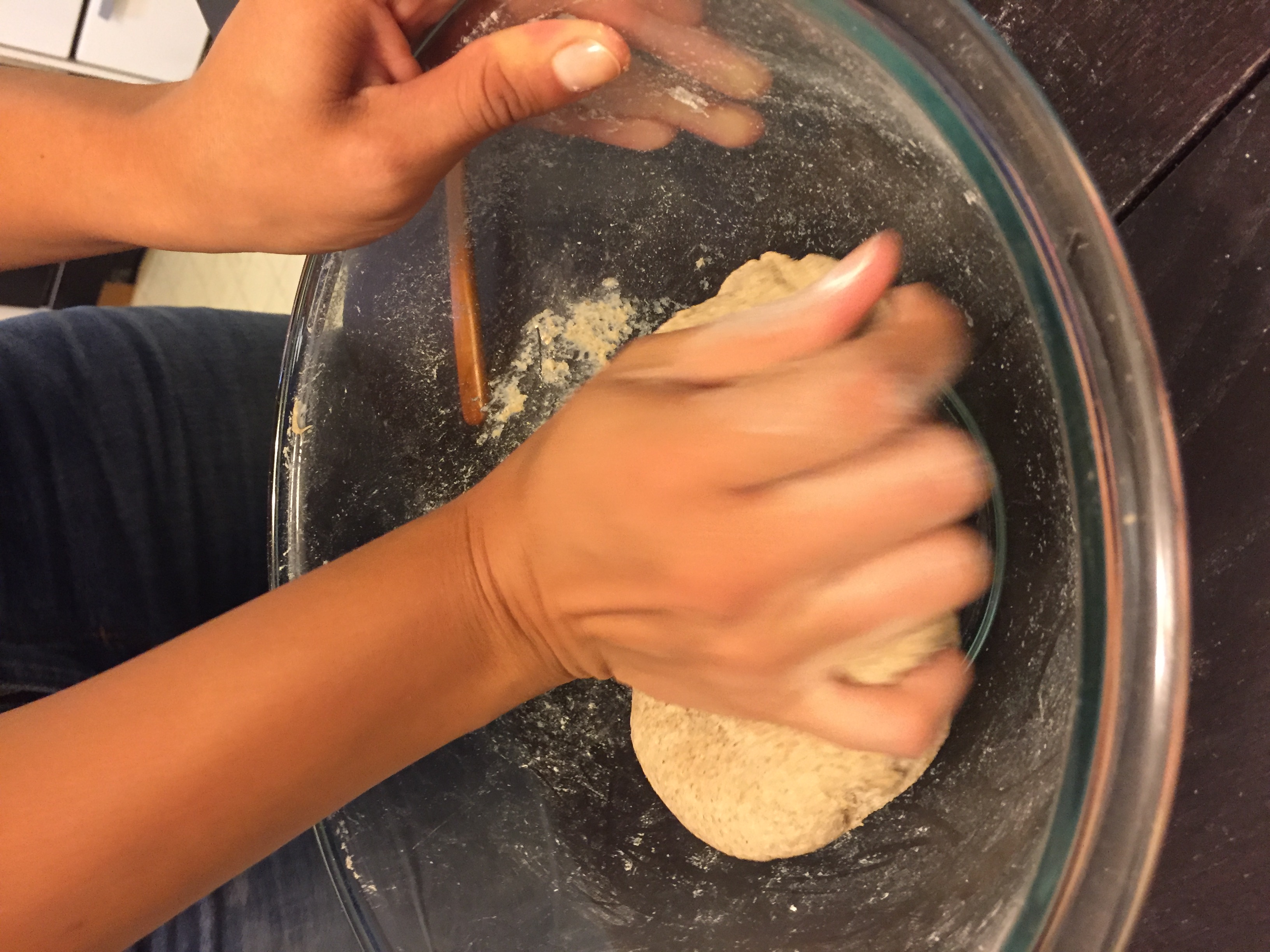

1) The students are asked to explore historical recipes for bread, bake their own bread, and impress a small object into the pith. They are also asked to develop a protocol for step 2 - the pour. See the Bread Making student activity sheet.

2) Part 2 takes place together in class (or can be done remotely). There is no worksheet, because part of the assignment is for the students to closely read the manuscript and develop their own experimental protocol. See the sample class plan below.

Themes: Embodied knowledge, everyday life, food, material culture, ephemeral art, art, sculpture, decorative arts, craft

Safety Notice: use of hotplates: If working with younger participants, the step of pouring melted wax can be performed by the instructor.

Duration: Approx 1.5 hours in class. Plus 2-3 weeks advance preparation in order for participants to learn to bake bread (in their own time)

Facilities: Can be done almost anywhere (if only using wax for pour), including remotely. If in a ventilated space (or in a fume hood), sulfur can be used

Materials and Tools:

- linseed (or vegetable) oil

- wax

- paintbrushes

- hotplates

- heatproof gloves

- heat resistant container for melting (eg. tin can / milk frothing pitcher/ saucepan / beakers

- stirring stick (e.g. chopstick, glass rod, spoon)

- plate / newspaper (something to contain mess)

- trivet or other heatproof surface

- paper towels

- Optional: a way to repair flaws or leaks in your molds, such as masking tape or modeling clay like plasticine

- Standard fire safety equipment (e.g. fire extinguisher and/or blanker)

If using sulfur:

- yellow sulfur powder

- nitrile gloves

- thermometer

Resources

Bread Making student activity sheet

Presentation: Step-by-step instructions for bread molding and casting

Videos by Vassar College students showing the process and result

Video of Making and Knowing Director Pamela Smith introducing “skillbuilding” exercises, including breadmolding and culinary reconstructions.

Suggested reading on Historical Breads (to assign for class and/or further information)

- If you only assign one piece of reading on breads in European history, we suggest Le Pouésard, Emma. “Pain, Ostie, Rostie: Bread in Early Modern Europe.”.

Suggested reading on Embodied Knowledge

- Tillmann Taape, “The Body and the Senses in Ms. Fr. 640: Towards a ‘Material Sensorium’.”

- Emma Le Pouésard, “Bread as Mediating Material: Tactile Memory and Touch in Ms. Fr. 640.”

- Ann-Sophie Lehmann, “Wedging, Throwing, Dipping and Dragging – How Motions, Tools and Materials Make Art,” Folded Stones, eds. Barbara Baert and Trees de Mits (Institute for Practice-based Research in the Arts: Ghent 2009), pp. 41-60.

- Raymond Tallis, “Grasping the Hand,” in The Hand: A Philosophical Inquiry into Human Being (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003), 21–43

Further reading on Embodied Knowledge (perhaps for more advanced students)

- Erin O’Connor, “Embodied knowledge in glassblowing: the experience of meaning and the struggle towards proficiency,” Sociological Review (2007): 126-141.

- Julian Thomas, “Phenomenology and Material Culture,” in Handbook of Material Culture, ed. Christopher Tilley et al. (Sage 2006), 43-59.

- Tim Ingold, The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill (London and New York: Routledge, 2000), chs. 18-19 (pp. 339-361).

Helpful resources in Secrets of Craft and Nature

Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, edited by Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano. New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020.

- Le Pouésard, Emma. “Pain, Ostie, Rostie: Bread in Early Modern Europe.”

- Le Pouésard, Emma. “Bread as Mediating Material: Tactile Memory and Touch in Ms. Fr. 640.”

- Landsman, Rozemarjin and Jonah Rowen. “Uses of Sulfur in Casting.”

- Lim, Min. “To Shrink an Object: Bread Molding in Ms. Fr. 640.”

- Sulfur-Passed Wax

- Landsman/Rowen, “Uses of Sulfur for Casting.”

- Kang, “Black Sulfured Wax.”

Note: for additional help and resources, try following the linked field notes in the essays above.

Sources on Making Sixteenth-century Bread

- John Evelyn’s bread

recipes, including varieties of French bread

- working transcription of Evelyn’s recipes by Reut Ullman, Columbia University

- Culinary and medicinal recipe book of Beulah Hutson, c.1660-1685, which contains a recipe for French Bread (pp.22-23)

- The Food Timeline- Bread History (good bibliography): http://www.foodtimeline.org/foodbreads.html#breadhistory

- Early English Bread Project: https://earlybread.wordpress.com/

- The Recipes Project: http://recipes.hypotheses.org/

- The Wellcome Library has digitized nearly all its recipe manuscripts. You can search the library here: http://wellcomelibrary.org/

- Monumenta Culinaria et Diaetetica Historica: a corpus of culinary & dietetic texts of Europe from the Middle Ages to 1800: https://www.staff.uni-giessen.de/gloning/kobu.htm

- Dutch Cooking History (with some English content): http://www.kookhistorie.nl/index.htm

Primary sources on the uses of bread in the early modern workshop

If you have time, search in additional primary sources for other uses of bread in the workshop:

- Alessio Piemontese, Book of Secrets (1555); various English versions on EEBO; French versions on Gallica; Italian versions in rare book collections.

- (For English: Search for Ruscelli, Girolamo, The secretes of the reuerende Maister Alexis of Piemount Containyng excellent remedies against diuers diseases, woundes, and other accidents, with the manner to make distillations, parfumes, confitures, diynges, colours, fusions and meltynges. … Translated out of Frenche into Englishe, by Wyllyam Warde (1558).

- Hugh Platt, The Jewell House of Art and Nature: Containing divers rare and profitable Inventions, together with sundry new experimentes in the Art of Husbandry, Distillation, and Molding (London, 1594). EEBO

- Cennino Cennini, Il libro dell’Arte (The Craftsman’s Handbook), trans. Daniel V. Thompson, Jr. (New York: Dover, 1960).

- Vannoccio Biringuccio, Pirotechnia (1540), trans. Cyril Stanley Smith and Martha Teach Gnudi (repr., Cambridge, MA, 1966).

- Theophilus, The Various Arts: De Diversis Artibus, ed. and trans. C. R. Dodwell (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986).

- Benvenuto Cellini, Two Treatises, trans. C. R. Ashbee (repr. 2006).

Explaining the Processes of Molding and Casting

- The difference between molding and casting (according to the Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus): Molding is giving form to something by use of a mold, and usually refers to pressing a material into the mold, as distinct from pouring liquid material into the mold, which is referred to as “casting.”

- For an illustration of molding and casting, watch VIDEO: Making a Medal Using the Sand Casting Process from the Frick Collection in collaboration with M&K.

On Historical Reconstruction as Historical Method

- Ken Albala, “Cooking as Research Methodology: Experiments in Renaissance Cuisine,” Renaissance Food from Rabelais to Shakespeare: Culinary Readings and Culinary Histories, ed. Joan Fitzpatrick (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2010), pp. 73–88.

- Hjalmar Fors, Lawrence M. Principe, and H. Otto Sibum. ‘From the Library to the Laboratory and Back Again: Experiment as a Tool for Historians of Science.’ Ambix 63, no. 2 (2016): 85–97.

- Lawrence Principe, “Chymical Exotica in the Seventeenth Century, or, How to Make the Bologna Stone” Ambix 63 (2016): 118-44.

- Ad Stijnman, “Style and technique are inseparable: art technological sources and reconstructions,” Art of the Past. Sources and Reconstructions. The proceedings of the First Symposium of the Art Technological Source Research Study Group, ed. by Mark Clarke, Joyce H. Townsend, and Ad Stijnman (Amsterdam: Archetype, 2005): 1-8.

- For an example of an exemplary reconstruction experiment by a conservator, see Maartje Stols-Witlox, “Sizing layers for oil painting in western European sources (1500-1900): historical recipes and reconstructions,” Proceedings of the Second ATSR Symposium (2008), pp. 148-163.

- Pamela H. Smith “Historians in the Laboratory: Reconstruction of Renaissance Art and Technology in the Making and Knowing Project.” Art History 39, no. 2 (2016): 210–33.

- Tillmann Taape, Pamela H. Smith, and Tianna Helena Uchacz. “Schooling the Eye and Hand: Performative Methods of Research and Pedagogy in the Making and Knowing Project.” Berichte Zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte 43, no. 3 (2020): 323–40.

About Teaching Bread Making and Molding

- Sophie Pitman, “Baking and Knowing: Iterative Processes and Iterative Teaching in a Historical Laboratory,” Detours: Social Science Education Research Journal 2 (1), 2021, 33-41.

Sample Class Plan

Discussion: Recipe Research and Making Bread

We recommend starting class with a group discussion about each student’s experience baking bread and exploring recipes for bread. Suggested questions:

- Why do you think there are so few recipes for bread in early modern sources?

- What is bread as a material in the workshop?

- What was it used for in the sixteenth century?

- What properties does it have that make it useful?

- Does it fit into some sort of informal taxonomy of materials and properties?

- Today we take bread for granted as a food, but how might its uses in the workshop re-orient that understanding?

Activity: Wax Casting

The activity sheet asks students to put together an experimental protocol for the wax casting from the entries in Ms. Fr. 640. We recommend you discuss these with the group, and invite experimentation. However, for a successful and safe activity, we recommend that any protocol should include these essential steps:

- melt wax at low heat on a hotplate

- (optional) brush the hollow of the breadmold with vegetable oil to make the unmolding easier. If students omit this step, they may have to soak the breadmold in order to remove all the bread pith from the cast object.

- place the mold on a surface covered with newsprint, paper plates, or similar to catch any spillages

- the molds can be fixed in place with masking tape

- carefully pour melted wax into the mold

- let the wax cool completely before attempting to remove the object

Discussion: Breadmolding, and bread as a material in the workshop

Suggested questions:

- To whom might this process be useful? I.e., why would you need to make a temporary mold of a small object?

- What do you learn by doing it yourself that you would not consider when just reading through the instructions?

- Does this raise further research questions you might like to pursue?

- Based on your experience of breadmolding, what can we (as historians of art/science/material culture/etc.) learn from historical reconstruction?