Making Lake Pigments

The Making and Knowing Project has used lake pigment making as a core skill-building exercise for its students. M&K has often assigned lake pigment making alongside verdigris growing, which were then followed up by a paint making and testing activity. Nevertheless, lake pigment making can be done on its own.

Learning Objectives

The activity of making lake pigments from modernized historical recipes has several potential learning outcomes, which can include:

- consider the relationship between historical and modern materials and tools

- understand how units of measure were communicated before the age of standardization

- interpret how the steps described in historical recipes might be modernized

- consider the labor involved in the production of historical art materials and artworks

What are Lake Pigments?

Lake pigments are a type of pigment prepared from organic natural colorants: plant and animal sources. As most organic natural colorants are soluble, they cannot be mixed directly with a binding medium and therefore cannot be used as a pigment. To be used as a pigment, these colorants must therefore be extracted as a solulble dye and then made insoluble by precipitating (or adsorbing) the dye onto a colorless or white, insoluble, relatively inert substrate.

In short: lake pigments are made by extracting a dye from an organic material and then turning that dye into a powder.

Jo Kirby et al, Natural Colorants for Dyeing and Lake Pigments: Practical Recipes and their Historical Sources (Archetype, London, 2014).

If you are not already familiar with historical pigments and natural colorants, refer to Presentation: Cochineal Lake: History, Chemistry, and Preparation for more complete information and further explanation of natural colorants and lake pigments.

See also Presentation: Introduction to Pigments & Paints.

What are Pigments More Generally?

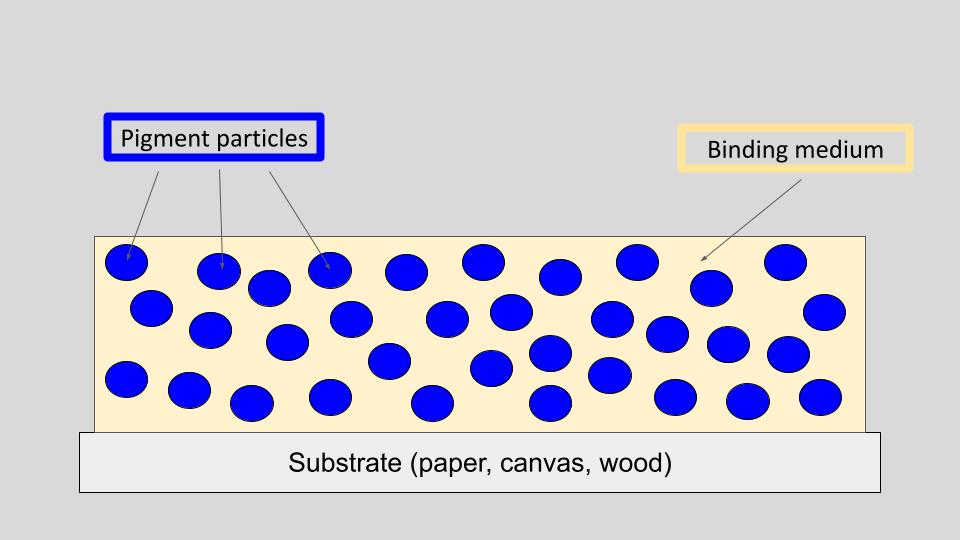

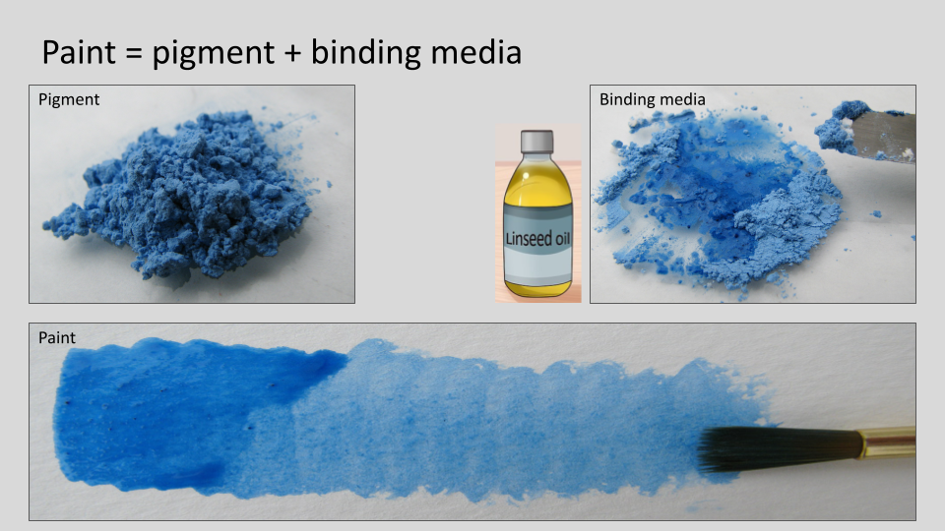

Pigments are colored, insoluble particles that, when combined with a binding medium, create paint that can then be applied to a substrate. Pigments can either be natural or synthetic. Historically, most pigments were sourced from the natural environment. Since the nineteenth century, the synthesis of pigments in industrial settings has become very common, ensuring consistent quality and new formulations.

Natural pigments generally come in three varieties:

- mineral: from mineral ores, semi-precious stones, and even gemstones.

- earth: from colored soils. These are also, technically, a form of mineral pigment.

- organic: from plants and animal sources. Lake pigments fall under this category.

Pigments are most often encountered as a component of paint. In short: Pigment + Binding Media = Paint

For more on paint making, refer to Presentation: Introduction to Pigments & Paints

Lake Pigments in Use

Lake pigments are typically found in top layer of paintings because their particles are translucent and are thus conducive to being used as thin glazes. As the entry “Glazing” on fol. 66r of Ms. Fr. 640 notes, “one commonly glazes with colors that do not have body, such as lake & veridigris.”

In practice, lake glazes could be used to create various subtle effects in painting. For example, the layer of “blush” painted over the cheek of a portrait might be done in a red lake pigment. This might reflect the use of lake pigments in women’s cosmetics. Fol. 58r of Ms. Fr. 640, the entry “Painter” includes the following observatino: “And thus they pounce the lake on their cheeks & then, with another clean cotton, they soften it.”

Historical Recipes for Lake Pigments

There are numerous recipes in historical sources from the late medieval period onward for making lake pigments. These include:

- Cennino Cennini, Il Libro dell’Arte(The Craftsman’s Handbook)

- Various manuscript sources compiled in Mary P. Merrifield, Medieval adn Renaissance Treatises on the Arts of Painting

A particularly readable example is taken from the so-called “Paduan Manuscript,” given in Mary P. Merrifield, Medieval and Renaissance Treatises on the Arts of Painting: Original Texts with English Translations (1849, Dover Publications, 1969), pp. 701-702.

Un altra sorte di lacca fina. - R. Piglia 12 grani di cocciniglia, o grana fina fatta inpolvere, si pone in due oncie di lissivio lasciandola in infusione due hore incirca poi si cola per pano lino, e si mette sopra cenere calda, quando vorrà bollire vi si aggiunge quanto due piselli d'allume di rocca in polvere, quando il liscivo farà schiuma grossa incarnata all' hora si getta tutto in un panno lino steso, e passarà il lissivo chiaro restando la schiuma nel panno, quale si fa seccare, e si fa tavolette.

Another sort of fine lake. Take 12 grains of powdered cochineal or fine grana, add to it 2oz of ley; leave the infusion for about 2 hours; strain it through a linen cloth and put it over hot cinders; When it boils add to it pulverized roche alum of the size of 2 peas then the ley will make a thick red scum; as soon as this happens throw it all onto a stretched linen cloth, when the clear ley will pass through leaving the coagulum on the cloth, which coagulum must afterwards be dried and made into tablets.

Such historical recipes have been updated so that they can be made in the modern lab or kitchen. For modernized recipes, see Jo Kirby et al, Natural Colorants for Dyeing and Lake Pigments: Practical Recipes and their Historical Sources (Archetype, London, 2014), chapter 5.

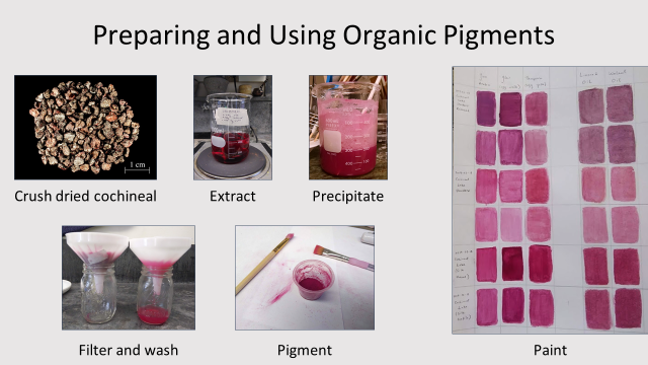

The basic steps involved in making lake pigments are:

- extract a colorant from a plant or insect by crushing it and soaking it in water

- add either A) an acid or B) a base to that colored water and heat it for a time, the better to extract the color

- catalyze a chemical reaction by adding either A) a base to your acidic solution or B) an acid to your basic solution (i.e., make a “volcano” reaction)

- let the reaction settle and then pour the solution through a filter; a precipitate will be left behind in the filter

- rinse the precipitate one or two more times until the water runs clear

- let it dry and scrape it from the filter. This is your pigment.

These steps are illustrated in the picture below:

Lakes can be made from a variety of natural colorants. Natural colorants can be extracted from plants, such as madder roots, buckthorn berries, weld stems, logwood bark, and animals, such as cochineal insects and mollusk secretions.

Cochineal | Brazilwood | Weld | Green (Unripe) Buckthorn Berries

Ripe Buckthorn Berries | Sumac | Dyer’s Broom | Turmeric

Walnut Hulls | Logwood | Madder | Oak Galls

Teaching Lake Pigments

Lake-Making in the Classroom: Activities

- Making Lake Pigment from Cochineal - hands-on lesson plan and assignment for transforming natural colorants in cochineal insects into a pigment

- Making Lake Pigment from Madder - hands-on lesson plan and assignment for transforming natural colorants in madder roots into a pigment

Lake-Making in the Classroom: Field Notes

- Making Pigment from Madder: a Trio of Recipes - helpful step-by-step fieldnotes

- Less detailed step-by-step fieldnotes for making lake pigments from cochineal, madder, ripe buckthorn berries, and brazilwood PDF

- A sample card painted from lake pigments in various binding media [PNG]

Lake-Making in the Classroom: Presentations

- Presentation: Cochineal Lake: History, Chemistry, and Preparation

- Presentation: Madder Lake: History, Chemistry, and Preparation

Lake-Making in the Classroom: Reflection Assignments

- Pigment-Making Lab Reflection Assignment [DOCX] [PDF]

- Pigment-Making Lab Reflection Assignment Background Document [DOCX] [PDF]

Lake-Making in the Classroom: Recipe Handouts

- Cochineal (standard recipe; yields pink) [DOCX] [PDF]

- Cochineal (reversed recipe; yields violet) [DOCX] [PDF]

- Madder (standard; yields ruddy red) [DOCX] [PDF]

- Weld (standard; yields pale yellow) [DOCX] [PDF]

- Logwood (standard; yields smoky purple) [DOCX] [PDF]

Lakes in Ms. Fr. 640

There are no recipes for making lake pigments in Ms. Fr. 640. There are, however, numerous references to lake pigments across the manuscript.

Pigments and Lakes in Ms. Fr. 640

For an essay exploring pigments, including lake pigments, in the manuscript, see Jo Kirby and Marika Spring, Ms. Fr. 640 in the World of Pigments in Sixteenth-Century Europe.

Lakes, Trade, and Labor in Ms. Fr. 640

Materials for a classroom activity exploring lake pigments in Ms. Fr. 640 (range of use, formats, and associated materials) and their relevance to global trade and labor practices: