Historical Culinary Recipe Reconstruction

Cooking is an almost universal activity – it is an art, a craft, a science – and yet most people do it without categorizing it as such. Cooking can provide a way for instructors to introduce hands-on experiments and close textual analysis to their students, many of whom will be used to following instructions from recipes and may feel more comfortable engaging in a hands-on activity in a kitchen than a studio, lab, or classroom. It is also very suitable for at-home assignments, or in-class activities, as most processes can be conducted in a home or institutional kitchen.

Learning Objectives

The Historical Culinary Recipe activity was conceived as one session (with the students working in their kitchens) at the start of a semester-long course. (See the Craft and Science syllabus and the Hands-On History syllabus.) This assignment works well as a way into the methodology, but could be expanded into a series of sessions on different kinds of food, cookbooks across time, or the material culture and textual world of cookery. It raises questions about tacit knowledge, the historicity of materials and tools (and how to source them today), how to adapt protocols and make compromises, what counts as successful reconstruction, and how hands-on experimentation is a form of close reading. If conducting the advanced optional assignment, it can be used to generate a reconstruction template for students to follow when conducting later experiments.

We recommend that you encourage your students to work in groups, have them bring their results to class to eat (if safe!) together as they present their findings. This is also a wonderful community-building exercise.

Food in Ms Fr. 640

Ms Fr. 640 only contains a small number of recipes for food (see, for example “Making millas” (fol. 20r) or “Excellent mustard” (fol. 48r)), but workshop practice intersects with food and drink on several occasions. The author-practitioner describes how to taxidermy animals by drying them in the oven, “after the bread has been taken out,” suggesting that food preparation took place alongside craft practices (fol. 129v). He also uses bread as a molding material (fols. 140v and 156r) and as an ingredient in making black varnish (fol. 4v). In the early modern period, food was always considered as adjacent to medicine. To avoid suffering from inhaling toxic fumes when making silver run, the author-practitioner advises to “take in the morning good buttered toast, and hold the said butter, or zedoary, or gold coins, in your mouth, and cover your face with a cloth from the eyes down” (fol. 123v).

Themes

Embodied knowledge, the body and the senses, historical reconstruction (especially questions of historical “authenticity”), everyday life, food, material culture, craft, medicine.

Teaching Materials

Guide to historical recipes and collections

Finding Recipes

If you are working with advanced students, such as graduate students or specialist undergraduates, we recommend you invite your students to explore the resources suggested in the above “Guide to historical recipes and collections” and select a recipe themselves. However, if working with less experienced students, you may wish to offer them a few suggestions. Here are some examples that have worked well for us by dint of being interesting and somewhat obscure:

Wellcome MS 213

- “A Syrupe of Lycoresse good for the Lunges and Shortnesse of the Breath” (p. 258)

- “A Syrupe of Vinegar good for to cool in any Fever” (p. 259)

Harleian MS 279

- “Ryschewys & Fryez” (p.45)

- “Browne Fryes” (p. 83)

- “Gely” (pp. 86–87)

Mayerne, Archimagirus

- “Pastry Cooks Varnishing” (p. 48)

- “Quindiniacks of Ruby colour” (p. 99)

Le Menagier de Paris

- Beverages for invalids (p. 109)

We encourage you to see whether your institution has any manuscript or printed recipe collections in the library; this could be an opportunity to take your students to work with primary sources available on campus.

Sourcing Materials

One of the key challenges in this assignment is to source ingredients and processes that closely resemble or emulate historical ones. This inevitably involves compromises, and raises productive questions about what historical “authenticity” actually means and to what extent it is attainable in historical reconstructions.

If you can, provide your students with a small budget and ask them to source their own ingredients. They may come up with novel solutions to material sourcing challenges, which prompts great in-class discussions.

Discussion Questions:

How did you source ingredients? Did you have to make compromises? Did you have to research any words?

What was missing from your recipe? Did it contain enough information for you to follow step-by-step, or did you need to make some interventions or fill in gaps?

What research questions did this process raise for you?

What might this suggest about the intended reader of this book?

What can this tell us about food / cooking / a specific material or process from the past?

Materials suitable for graduates and undergraduates

Ken Albala, “Cooking as Research Methodology: Experiments in Renaissance Cuisine,” Renaissance Food from Rabelais to Shakespeare: Culinary Readings and Culinary Histories, ed. Joan Fitzpatrick (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2010), pp. 73–88.

Syrup of Violets and Science video (ca 8 mins).

“The Best Medicine,” RadioLab podcast (ca 30 mins).

Additional readings for more advanced students

For a discussion about different approaches to historical reconstruction (a different point of view from Albala’s strict call for “authenticity”)

Fors, Hjalmar, Lawrence M. Principe, and H. Otto Sibum. “From the Library to the Laboratory and Back Again: Experiment as a Tool for Historians of Science.” Ambix 63, no. 2 (2016): 85–97

Lawrence Principe, “Chymical Exotica in the Seventeenth Century, or, How to Make the Bologna Stone” Ambix 63 (2016): 118-44.

Ad Stijnman, “Style and technique are inseparable: art technological sources and reconstructions,” Art of the Past. Sources and Reconstructions. The proceedings of the First Symposium of the Art Technological Source Research Study Group, ed. by Mark Clarke, Joyce H. Townsend, and Ad Stijnman (Amsterdam: Archetype, 2005): 1–8.

On recipes

Explore the Recipes Project Archive online

Appelbaum, Robert. Aguecheek’s beef, belch’s hiccup, and other gastronomic interjections: literature, culture, and food among the early moderns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Goldstein, David B. Eating and Ethics in Shakespeare’s England. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2013. (E-book, also available in print)

Leong, Elaine. Recipes and Everyday Knowledge: Medicine, Science and the Household in Early Modern England (University of Chicago Press, 2018).

Rabisha, William. The whole body of cookery dissected, taught, and fully manifested, methodically, artificially, and according to the best tradition of the English, French, Italian, Dutch, &c., or, A sympathie of all varieties in naturall compounds in that mysterie: wherein is contained certain bills of fare for the seasons of the year, for feasts and common diets : whereunto is annexed a second part of rare receipts of cookery, with certain useful traditions : with a book of preserving, conserving and candying, after the most exquisite and newest manner … 1661, 1673 and 1682 editions available via EEBO.

Tomasik, Timothy J. At the Table: Metaphorical and Material Cultures of Food in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Turnhout: Brepols, 2007. (E-book, also available in print)

Willan, Anne. The cookbook library : four centuries of the cooks, writers, and recipes that made the modern cookbook. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Additional materials

Video of Making and Knowing Director Pamela Smith introducing “skillbuilding” exercises, including culinary reconstructions.

Sample student reconstructions

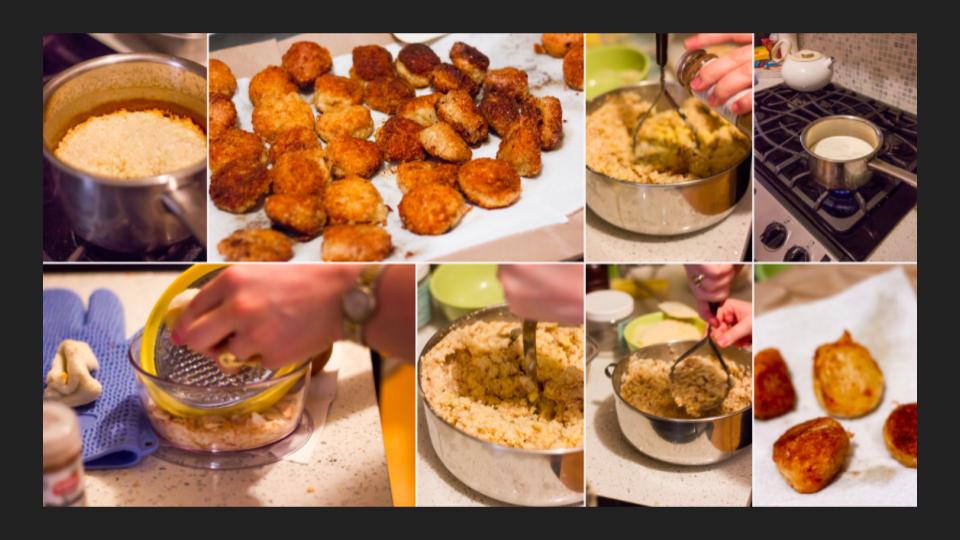

Video: “Ryschewys close & fryez” by Amelia Wright, Caleb Mitchell, Magdalena Ramos Mullane (Vassar College)

Explore the Making and Knowing Fieldnotes site, some good examples include:

Isabella Lores-Chavez, and Caitlyn Sellar, “Making Quindiniacks”

Diana Mellon, Michelle Lee, and Yijun Wang, “Excellent Mustard.” Also see the essay about the “Excellent Mustard” reconstruction: Diana Mellon, Excellent Mustard

Optional additional assignments:

Encourage your students to write their reflections on the assignment in a Historical Culinary Reconstruction Discussion Document

Ask your students to collaboratively compile a Reconstruction Template document (i.e. a list of things to keep in mind when doing a reconstruction)