Dyeing

The Making and Knowing Project has undertaken experiments in dyeing with natural colorants as a way to engage with various entries in Ms. Fr. 640 and as a preliminary step to making lake pigments. Additionally, M&K has led several community outreach activites on dyeing with natural colorants that can be ported directly into the classroom. These activities and their contexts are also described on the Making and Knowing Resources in Use section of the Companion.

If you are already familiar with historical dyes and natural colorants, you might want to explore the presentation Cochineal Dye: History, Chemistry, and Preparation which offers more extensive information than is offered in summary on this page.

Learning Objectives

The activity of dyeing with natural colorants following modernized historical recipes has several potential learning outcomes, which can include:

- consider the relationship between historical and modern materials and tools

- understand how units of measure were communicated before the age of standardization

- interpret how the steps described in historical recipes might be interpreted in a modern context

- consider the relationship between dyes and pigments and thus between the textile trade and art production

What is a dye?

A dye is a compound that absorbs into and colors another material and is often a complex organic compound (Conservation and Art Materials Encyclopedia Online (CAMEO)). Until the onset of synthetic dyes in the mid-nineteenth century, most dyes were sourced from natural colorants such as plants, insects, lichens, and shellfish.

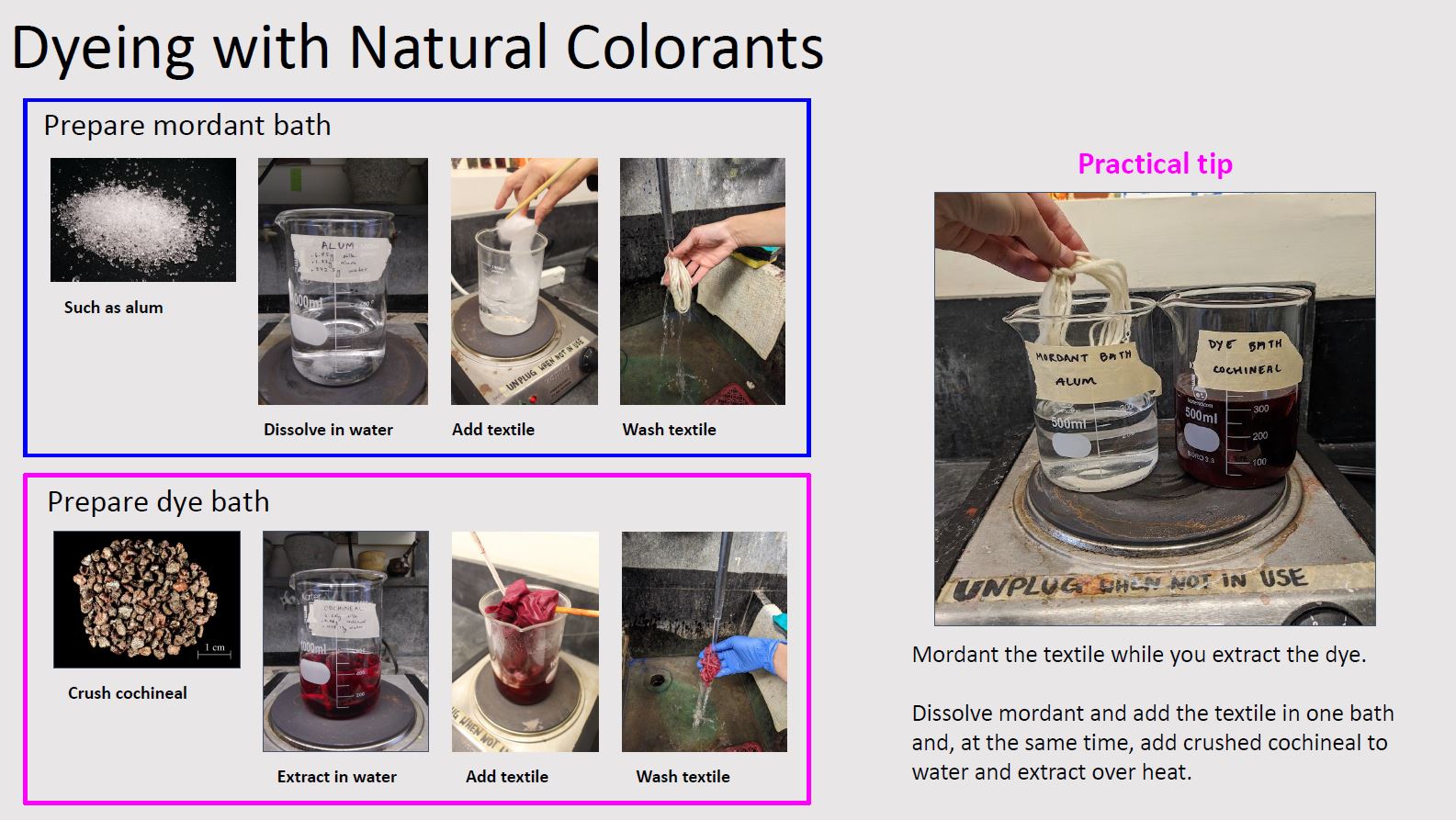

In order to dye materials (typically textiles, but also wood, paper, leather, and ivory, for example), the natural colorant must first be extracted from the dyestuffs (the plant, insect, etc.). This is most usually done by placing the dyestuffs in water and using either time (soaking) or heat (bringing to a simmer) to extract the soluble colorant into the water. The materials can then be placed into this dye bath to take on color.

Natural dyes can be categorized into one of three processes used to extract the colorant and dye materials:

- Direct dyes

- Mordant dyes

- Vat dyes

Mordant dyes

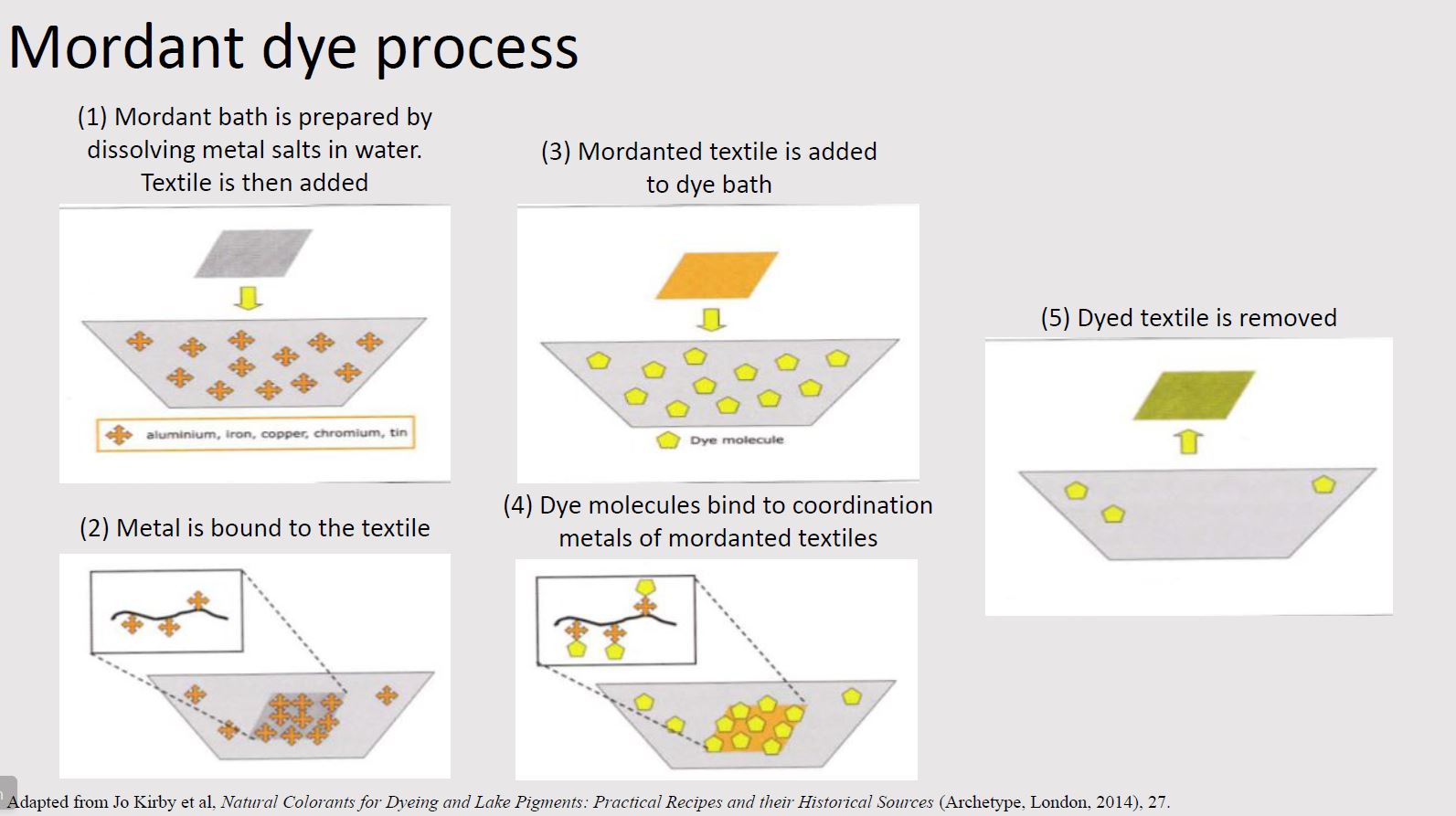

The largest class of natural dyes is mordant dyes. In this process, textiles must first be treated with a mordant (typically a metal salt or coordination metal) in order to bind the dye more permanently to the textile. The textile binds to the mordant which in turn binds to the colorant. The mordant thus acts as a bridge between the textile and colorant.

The most common mordant is aluminum, typically in the form of alum (aluminum potassium sulfate). Other mordants include iron sulfate, copper sulfate, and tannins.

Jo Kirby et al, Natural Colorants for Dyeing and Lake Pigments: Practical Recipes and their Historical Sources (Archetype, London, 2014).

An Example Historical Recipe and its Modernization

The recipe below is for a mordant dye made from the scale insect cochineal.

De’ secreti del reverendo signore Alessio Piemontese (1558) as translated from the Dutch in Jo Kirby et al, Natural Colorants for Dyeing and Lake Pigments: Practical Recipes and their Historical Sources (Archetype, London, 2014), 37–38.

To dye silk carmine. First, you will rasp or scratch hard soap very finely, and let them [the soap shavings] dissolve in plain water; after that put your silk in a small bag made of linen or fine canvas, and put it in a kettle with the aforesaid soap and water. Let this boil for half an hour, moving it around regularly so it does not burn, then take it from the fire, wash it in salt water, and after that in sour water. Take also to every pound of silk a pound or more of rock alum dissolved in cold water, and be sure there is enough water; wherein you will put your silk without any bag, and let it lay therein without fire for eight hours. Then take it out, wash it in fresh water, then in salt water, and then again in fresh water, and do not let it dry but put it all wet into a kettle with the carmine well pestled and sieved, that is, three ounces for each pound of silk… And when it starts boiling then put in the silk prepared as above, and let it boil for a quarter of an hour. At last you will take it from the fire, and let it dry in the shade, and you will have a very excellent dyeing.

The recipe above from Piemontese has informed the standardized recipe for cochineal dye in Jo Kirby et al, Natural Colorants for Dyeing and Lake Pigments: Practical Recipes and their Historical Sources (Archetype, London, 2014), Chapter 5. The standardized recipe includes potash (potassium carbonate) as an optional additive. Potash is not typically found in recipes for cochineal because it results in a paler color, but it is attested in some instances.

The standardized recipe begins with a mordant bath and is followed by a dye bath. Recipes for dyeing textiles often list ratios rather than outright amounts. The weight of textile will determine how much of the other ingredients are needed. The ratios in the example below are provided for 1g of textile.

Mordant Example: Alum

| Material | Amount /1g (g) |

|---|---|

| textile | 1.00 |

| alum | 0.20 |

| water | 50.00 |

Dye Example: Cochineal

| Material | Amount /1g (g) |

|---|---|

| textile | 1.00 |

| cochineal | 0.125 |

| potash (optional) | 0.0625 |

| water | 62.50 |

To know how much of the mordant, water, cochineal, and optional additive are needed, first weigh the textiles you plan to dye then multiply that amount by the ratios above. For example, if your textile weighs 10g, you will need 1.25g cochineal and 625ml water.

Teaching Dyeing

Presentations

- Cochineal Dye: History, Chemistry, and Preparation

- Dyeing: Step-by-Step Instructions

- Pictures of Common Natural Dyestuffs

Resources

- Sourcing Materials for Dyeing [DOCX]

- [PDF]

- Advice for Dyeing in the Home Kitchen [DOCX]

- [PDF]

- How to Calculate Mordant and Dyestuff Amounts [DOCX]

- [PDF]

- Automatic Mordant and Dyestuff Calculator [XLSX]

Activity Sheets and Handouts

- Student Assignment: Dyeing Textiles with Cochineal: A Historical Reconstruction

- (also available as a PDF)

- Handout: One-page Instruction Sheet for Mordant and Dye Process

- Handout: Historical Cochineal Dye Recipe - Piemontese (2 copies per page for printing as a student handout)

- Dyeing with Natural Colorants: All Essential Teaching Resources and Activity Sheets

Dyeing in Ms. Fr. 640

Dyeing appears in several guises in Ms. Fr. 640. A wildcard search for “*dye*” in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France reveals entries that instruct how to prepare natural dyestuffs, use dyed wools in artisanal making, and dye cheaper materials to imitate more costly ones. There are also entries for dyeing various materials, from leather and mats to wood. In fact, the manuscript includes a series of recipes for dyeing wood in all kinds of colors, scattered across folios from fol. 73r to fol. 79r, though the term “dyeing” is not used here explicitly.

There are also several essays in Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France that explore the entries on dyeing, including:

- Sophie Pitman, “Black Color for Dyeing, and the Place of Textiles in Ms. Fr. 640.”

- Yuan Yi, “Damasked Cloth.”

- David McClure, “Making Colored Wood in Ms. Fr. 640.”

References and Resources

- Kirby, Jo, Maartin van Bommel, André Verhecken, and Marika Spring. Natural Colorants for Dyeing and Lake Pigments: Practical Recipes and Their Historical Sources. London: Archetype Publications, 2014.

- Merrifield, Mary P. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to XVIIIth Centuries, on the Arts of Painting in Oil, Miniature, Mosaic, and on Glass of Gilding, Dyeing, and the Preparation of Colours and Artificial Gems; Preceded by a General Introd., with Translations, Prefaces, and Notes. J. Murray, 1849.

- CAMEO: Conservation & Art Materials Encyclopedia Online: http://cameo.mfa.org/wiki/Main_Page. CAMEO is a searchable information resource developed by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The MATERIALS database contains chemical, physical, visual, and analytical information on historic and contemporary materials used in the production and conservation of artistic, architectural, archaeological, and anthropological materials.

- Cardon, Dominique. Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science. Archetype, 2007.

- Gettens, Rutherford J., and George L. Stout. Painting Materials: a Short Encyclopedia. Dover Publications, 1966.

- Vejar, Kristine. The Modern Natural Dyer a Comprehensive Guide to Dyeing Silk, Wool, Linen, and Cotton at Home. Abrams, 2015.

- Dean, Jenny. Wild Color: The Complete Guide to Making and Using Natural Dyes Watson-Guptill, 2010.