Introduction

Collecting Medical Knowledge Across Generations

Historians of science agree that something pivotal happened in England in the latter decades of the sixteenth century, as medieval theories about the body or the natural world diminished in the face of new discoveries, new ideas, and a new experimental method. And yet, the reading habits of sixteenth-century English artisans, bureaucrats, merchants, and farmers tell a different story, one that this project seeks to explore. Early modern English people were avid collectors of medieval manuscripts filled with centuries-old texts related to medicine, astrology, agriculture, or craft manufacture.

Old Books, New Attitudes seeks to understand why early modern readers collected medieval medical and scientific knowledge in old manuscripts, how generations of readers engaged with these manuscripts over time, and what role these older books played in the development of new epistemologies associated with the scientific revolution.

The first stage of the project focuses on Trinity College Cambridge MS O.8.35, a later fifteenth-century guide to medical practice and one of at least five Middle English medical manuscripts owned by Henry Dyngley (ca. 1515-1589). EditionCrafter provides the ready-made infrastructure for a digital critical edition of TCC MS O.8.35 that encodes both the medieval origins, materials, and methods of the recipes and instructions original to the manuscript, as well as reader marks and signatures that demonstrate the use and reuse of the manuscript over time. If the prototype edition of TCC MS O.8.35 is a success, Old Books, New Attitudes will incorporate student researchers and produce digital editions of Dyngley’s other medieval manuscripts with the goal of reconstructing Dyngley’s library, and by extension, the sources he mined as author of Wellcome MS 244, a huge compendium of medical, alchemical, and meteorological knowledge.

The aim of the project is to reconstruct the intergenerational transference of medical and scientific knowledge in books, and to show how medieval sources played an important role in facilitating a culture of scientific exchange and inquiry in early modern England.

Henry Dyngley’s Collecting Habits

Henry Dyngley’s collecting habits were first noticed by the late Lister Matheson, Professor of English and Medieval Studies at Michigan State University, whose initial notes on Dyngley’s annotations in two manuscripts and one printed book held in the Welcome Collection were shared with this project’s lead researcher, Melissa Reynolds. Since 2013, Reynolds has identified Dyngley’s marginalia in another four fiftenth-century manuscripts, bringing the handlist of Dyngley’s library to a total of seven items:

- Wellcome Library MS 5262, a late fourteenth-century collection of Middle English medical recipes, possibly created at Winchcombe Abbey in Gloucestershire

- Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson C.506, a mid-fifteenth century manuscript composed of several, originally-separate manuscripts related to medicine, agriculture, and husbandry, which were joined together by a later medieval or early modern reader

- British Library MS Royal 17 A.xxxii, a manuscript from the first half of the fifteenth century containing Middle English texts on prognostication, an herbal, and a collection of medical receipts

- Trinity College Cambridge Library MS O.8.35, a later fifteenth-century Middle English all-purpose medical guidebook, identical in format and contents to Bodleian Library MS Add. B.60

- Trinity College Cambridge MS R.14.52, a mid-fifteenth century manuscript featuring several translations of learned, Latinate medical texts in Middle English

- Welcome Library MS 244, a later sixteenth- and seventeenth-century manuscript of medical, meteorological, and alchemical knowledge, begun by Henry Dyngley and completed by his descendants

- Wellcome EPB/A/7330, A newe book Entituled the Gouvernement of Healthe, by William Bulleyn, a medical manual and dietary published in London in 1558

Henry Dyngley was born around 1515, probably near his family’s manor home of Charlton in the parish of Cropthorne, Worcestershire. The Dyngley family had been in possession of that estate since the late fourteenth century, but in 1541, Henry inherited it from his father, John.

Very little is known of Henry or his manuscript collecting habits prior to the 1540s. It seems he did not attend university, nor had he yet attained much in the way of political or social stature. But, in the same decade in which he became lord of the manor of Charlton, Dyngley appeares to have developed an interest in medieval manuscripts, perhaps thanks to the dissolution of Winchcombe Abbey in 1539, when Dyngley was just twenty-four. Winchcombe was only about twenty miles from Dyngley’s manor at Charlton, and it was also very likely the locus of origin for Wellcome MS 5262. The manuscript is a beautiful, late fourteenth-century collection of medical recipes, into which Henry inscribed his name and initials. With three full-page illustrations of saints on its opening folios, decorated initials, and rows of neat Gothic script, Wellcome MS 5262 looks a good deal like the sort of manuscript that might have originated in a monastic scriptorium. Indeed, the final folio of Wellcome MS 5262 features a prayer, added by a later fifteenth-century reader, to St. Kenelm, patron saint of Winchcombe Abbey in Gloucestershire.

Image of a saint, censored by a later owner of Wellcome MS 5262; Credit: MS.5262, Medical Recipe Collection, England, 15th Century, Public Domain Mark, Wellcome Collection, London

Though Dyngley left no dated reader mark in Wellcome MS 5262, someone who possessed the manuscript after the dissolution and the upheaval of the English Reformation took care to partially obscure the illustrations of saints on the manuscript’s opening pages using the same technique found in another of Dyngley’s manuscripts, Bodleian MS Rawlinson C.506, which we can securely place in his hands before 1547.

Bodleian MS Rawlinson C.506, a thick manuscript of over 300 small paper pages, crammed with recipes, charms, verses on bloodletting, equine medicine, and treatises on planting, grafting, fishing, and hawking may also have come to Dyngley as a spoil of the dissolution. Before Dyngley owned the manuscript, it passed through the hands of “humfridus harrison Capellanus” (Humfrey Harrison, chaplain), who left a reader mark on the manuscript’s final page. He may well be the same Humfrey Harrison who was vicar of Alstonefield in Staffordshire in the later fifteenth century. Alstonefield was owned by the Cistercian abbey of Combermere, which means that the vicar’s belongings might have passed into the Crown’s possession upon the abbey’s surrender on 27 July 1538. For the next decade the whereabouts of the manuscript are unknown, but somehow by 1547 it was in the hands of Henry Dyngley, who added a new recipe “for migraines” to its pages, which he signed “by me henry Dyngley of Charleton in the parish of Cropthorne written by me the .14. day of august anno domini 1547 I being of the age 32.”

Over the next two decades Dyngley amassed another three fifteenth-century medical manuscripts as his fortunes and family increased. By 1550, Dyngley had married Mary Neville, daughter of Sir Edward Neville, a courtier close to Henry VIII. By 1553, when he was appointed Sheriff of Worcestershire for the first time, he was also the proud father of three sons: Francis, the eldest, followed by George and Henry. And by 1554, Henry had managed to procure yet another medical manuscript, Trinity College Cambridge MS O.8.35, a professionally-produced vernacular medical textbook, with recipes and treatises on uroscopy, on the four humors, on anatomy, and on “simples.” Just as in his other manuscripts, Dyngley used blank space in the Trinity College manuscript to add extra recipes. In 1557, he copied a list of “waters” onto the last page of the book, which he again signed and dated, “Henry Dyngley anno Christo 1557 xxx may at Adyngton in Buckinghamshire.”

Queen Mary’s death in 1557 perhaps heralded a return to stability for Dyngley, as England reverted back to Protestantism from the five-year Catholic interlude of Mary’s reign—though Dyngley appears to have remained in the Crown’s good graces under both Mary and Elizabeth. Around 1560, Dyngley began consolidating his landholdings in Cropthorne, bringing suit against the Dean and Chapter of the Cathedral at Worcester for rights to common lands pertaining to his manor at Charlton. That same year, he acquired both a new daughter, Mary, and another medical manuscript, British Library MS Royal 17 A.xxxii, which he again signed and dated over several folios. The following two years brought another two daughters in quick succession, Barbara and Alice, the last of Henry’s nine children.

Perhaps it was the births of Mary, Barbara, and Alice in Dyngley’s late forties that inspired him, sometime after 1563, to fill blank leaves toward the end of the Royal manuscript with a series of verses which he titled, “A godly exhortation for a father to his children.” The poem, excerpted from John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments and attributed to the Marian martyr Robert Smith, was originally written as a macabre invocation for Smith’s children to remember their father “in prison and in payne” and to reflect on their own mortality. In Dyngley’s hands, the poem took on a different tone. It is still a reflection on a father’s mortality and the ephemeral nature of familial bonds, but where the printed version in the Acts and Monuments ends with an extended reflection on the horrors of Catholicism and an admonition to reject that errant “whore of Rome,” Dyngley chose not to include those verses in his copy. Instead, Dyngley closed his poem thus: “I leave you here a little book to loke upon / to see your fathers face when he is dead and gone.”

If this verse can be read as a reflection of Dyngley’s intentions, then his collecting habits were more than a hobby. In the manuscripts he collected and annotated with his initials, he was constructing an archive of natural knowledge for his children. In 1564, just one year after “A father’s exhortation for his children” appeared in the first English edition of Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, Dyngley began work on his own “little book” to leave for his children when he was dead and gone: Wellcome MS 244, a manuscript that reorganized the knowledge he had collected from old manuscripts into a valuable reference for those who would follow him.

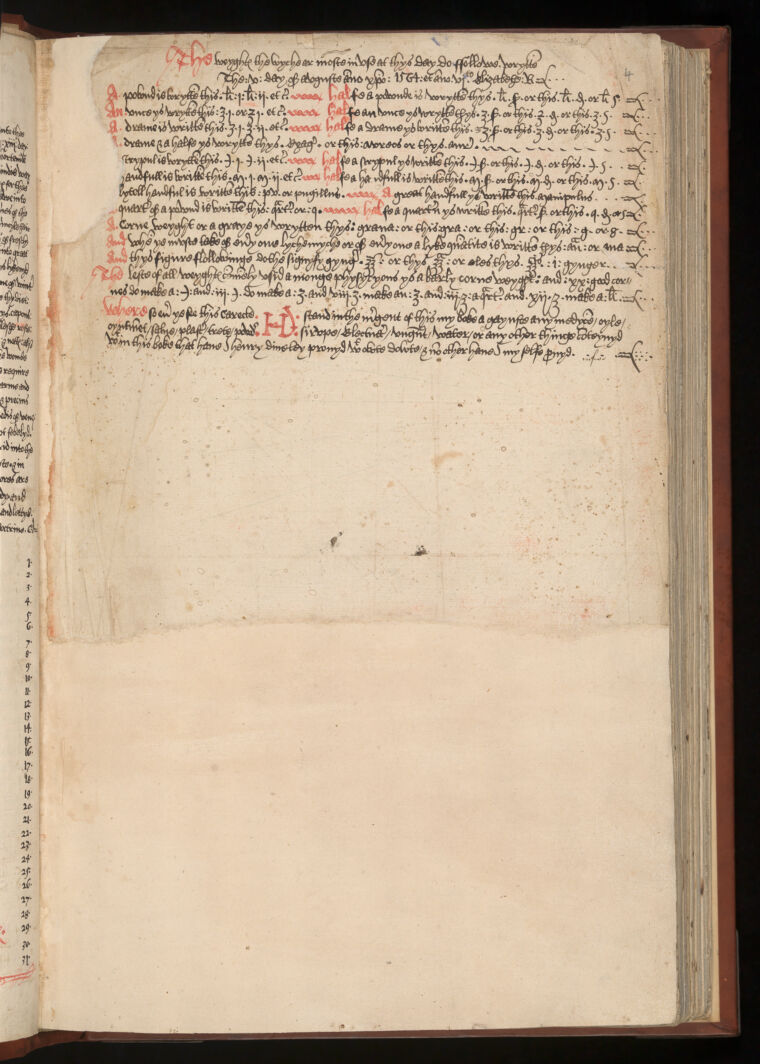

The manuscript Dyngley composed in 1564 opens with a kalendarium. Written in Dyngley’s own hand, the calendar is devoid of most of the saints’ days that filled medieval examples of the genre, but it features additions of astrological information for every month of the year. At the very back of the manuscript, Dyngley wrote notes about the weather that year (“The year of our lord god 1564 was the coldest spring & the windiest that ever I did see & it was the goodliest year of blooming of all manner of fruit trees”), followed immediately by a copy of a prognostication that would help him forecast future weather events. The prognostication was a version of the “Book of Thunders,” predicting weather and crop yields according to whether one hears thunder in a given month. He closed this section with a disclaimer to the reader about the value of the recipes he’d collected for his manuscript: “Where so ever you see this character HD stand in the margin of this my book, against any medicine, oil, ointment, salve, plaster, trete, powder, syrup, electuary, unguent, water, or any other thing contained within this boke, that have I, Henry Dineley proved without doubt & none other have I myself proved.”

Page from Henry Dyngley’s manuscript compilation, Wellcome MS 244, featuring his note describing his initials as marks of approbation; Credit: MS.244, Dineley/Dyneley (or Dingley/Dyngley), Henry, Public Domain Mark, Wellcome Collection, London

In 1573, a decade after he began composing his own recipe collection with this disclaimer about the value of recipes marked with an HD, at nearly sixty years old, Dyngley was still marking up old manuscripts. Alongside a vernacular treatise on reproduction in Trinity College Cambridge MS R.14.52, Dyngley wrote, “Note H D 1573.” At the back of the same massive (and beautiful) manuscript, he also updated a running list of the dates of Easter with a comment that in 1573 “easter was the xxii day of march.” It is the latest date that appears in any of his manuscripts. Sixteen years later, in 1589, Henry Dyngley died at the age of seventy-four.

About Trinity College Cambridge MS O.8.35

Trinity College Cambridge MS O.8.35 (hereafter TCC MS O.8.35) has the second oldest dated reader mark of the manuscripts we can securely place in his collection. The first of Henry’s marks appears on what was once the verso of the front cover of the manuscript, now front flyleaf 4v. On that page, he composed a key or glossary to help him identify or remember apothecaries’ symbols for a pound, an ounce, a dram, a scruple, and a grain. Underneath that table of weights and measures, he left a signature with a date: “1554, the first year of Philip and second year of Mary’s reign, the 22nd of March.” Then, at the close of the manuscript, on the recto of folios 126 and 127, Henry added another signature and date, “anno christo 1557 I wryght the xxx daye of maye” as well as place name: “Adyngton in Buckingegam shere.”

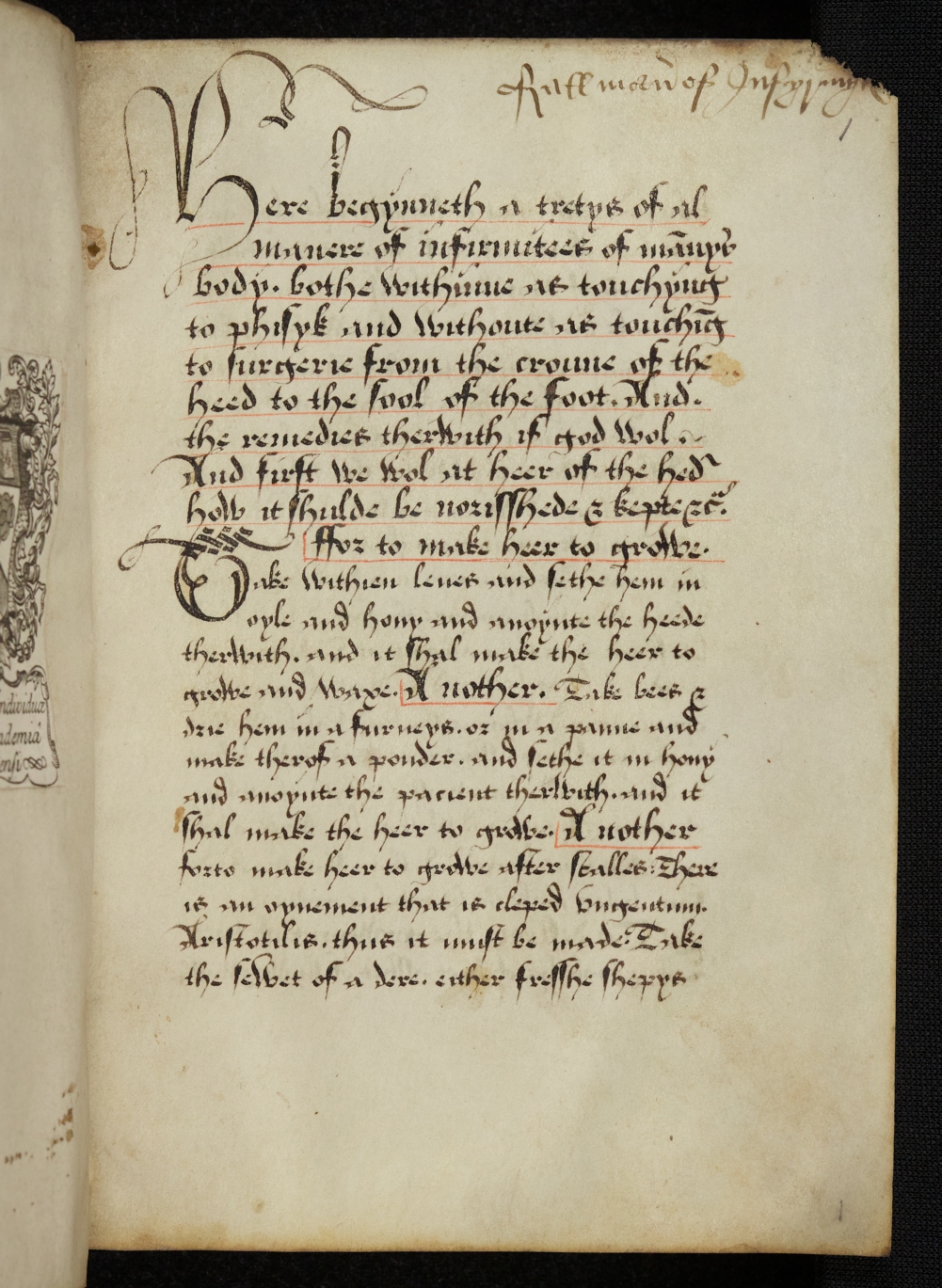

In between these signatures, the contents of TCC MS O.8.35 are medical in nature, and they match exactly the contents of another mid-fifteenth-century Middle English manuscript, Bodleian MS Add. B.60. In fact, not only are the contents of these two manuscripts identical, their formats are identical, too. Both manuscripts were composed on quarto-sized parchment in a neat and professional cursive script known as Secretary hand. The catalogue entry for Dyngley’s manuscript, TCC MS O.8.35, states that the manuscript has 127 pages and four flyleaves, roughly 215 mm high by 155 mm wide.

First page of TCC MS O.8.35, featuring the incipt of the medical recipe collection and three recipes, copied in a neat and professional Secretary hand; Credit: MS O.8.35, Trinity College Cambridge Library, CC-BY-NC 4.0

The contents of these 127 pages are as follows:

- “Here begynneth a treatys of al manere of infirmitees of mannys body”: medical recipes for various ailments, organized a capite ad calcem, or, from head to foot (ff. 1–52r)

- a brief treatise on diagnosing a patient based on the color of their urine (ff. 52v–57r)

- a short treatise on astrology and bloodletting, which may be an adaptation of the introduction to the thirteenth-century English physician Gilbertus Anglicus’s Compendium medicinae (ff. 57v–59r)

- a treatise on the four humors (ff. 59r–62v)

- a treatise on the four elements and the four ages (ff. 63r-65v)

- a short section on how to write weights and measures (f. 65v)

- a treatise on the signs and their relationship to the four humours and elements (ff. 65v-69v)

- a treatise on the names of the astrological signs and their relationship to Biblical narratives (ff. 69v-70v)

- “This table tellith of digestives symple & compound of every humour that is to say of colere, fleme, and melancolie”: medicines for the parts of the body arranged by simple and then compound (ff. 70v-83v)

- “Here folewen the entraailes of man and medicines also for certeyn parties of a mannys body” (ff. 85r-87v)

- “Here folewen now after trew and proved medicynes good and prophetable cures for dyverse infirmitees, grevaunces, and siknesse of mannys or womannes or childes body” (ff. 87v-112r)

- a few Latin recipes (ff. 112r-122v)

- a few recipes in English (ff. 122v-124r)

- recipes added in later xv and xvi c. hands (ff. 124v-125v)

Visit the folios page to read transcriptions of these recipes alongside a digital facsimile of the manuscript.